by Humphrey McQueen

A presentation given to Solidarity Breakfast on Radio 3CR, 4 March 2017

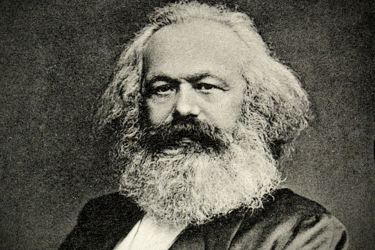

In introducing the second German edition of Capital, Marx refers to Hegel as ‘that mighty thinker’ who was being treated as ‘a dead dog’. Marx promises to distance himself that assessment by flirting with Hegel’s vocabulary. There’s never been a time since the publication of Capital 150 years ago this September when Marx was not also being dismissed as a ‘dead dog’.

In introducing the second German edition of Capital, Marx refers to Hegel as ‘that mighty thinker’ who was being treated as ‘a dead dog’. Marx promises to distance himself that assessment by flirting with Hegel’s vocabulary. There’s never been a time since the publication of Capital 150 years ago this September when Marx was not also being dismissed as a ‘dead dog’.

The difference between the reputations of Hegel and Marx derives from Marx’s contributions to working people as an activist and as ‘the greatest living thinker’, to quote Engels at his graveside. Marx’s involvement with class struggles why ‘there’s life in the old dog yet.’ Yet his commitment to the weak and to the poor, to the oppressed and to the exploited, is also why forests have been felled to spread the allegation that Marxism is dead and ought to be buried along with him.

The campaigns to prove that Marx is a ‘dead dog’ never go away. Indeed, they are heating up.

The Spectator had a cover story on 14 January ‘Finishing Off Marx’. A graphic cover showed the author driving a stake through Marx’s heart. The author was Giles Auty, himself a walking corpse. Auty used to rubbish contemporary art for The Australian. He knows so much about Marx that the most he could manage for the Spectator was to paraphrase of two articles that had just appeared in The Australian.

Why would a 250-year old weekly like The Spectator print such trivia? And why give a one-page piece star billing as the lead cover story? The answer is because Marx is more than a spectre haunting global capitalism. His analysis of capitalism is a living presence in the movements against that failed and broken system. The Spectator editors are smart enough to know Auty’s ramble could not convince anybody of anything. What they were doing was using his flim-flam as an excuse to circulate the cartoon assassination of Marx. The cartoon’s job was to reassure the Spectator’s reactionary readers that Marx was a political and personal monster.

So what had been in The Australian’s articles that deserved to be given star billing in The Spectator? The first appeared late in December when Kevin Donnelly repeated his demand that schools get ‘back to basics’ instead of what he calls ‘Marxist-inspired nonsense.’ It goes without saying that Donnelly has no idea what Marx said about education. He would be shocked to read this demand from The Communist Manifesto:

‘Combination of education with industrial production …’

And the same call again nearly 30 years later:

‘… an early combination of productive labour with education is one of the most potent means for the transformation of present-day society.’

I suspect that a few Marxists might be taken aback too.

The other article in The Australian was a reprint from The Times by the genetic determinist Matt Ridley. Ridley made a name for himself in the 1980s by vulgarising biology to justify Thatcherism. Wars and injustice are the products of our genes, according to Ridley. Human history might as well never have happened. From this standpoint, Marxists are unscientific because we locate human nature in socio-economic conflicts.

Our starting point as historical materialists is that human beings become what we do – as individuals and as a species. Not everything is possible for us. Yet we are constantly shifting the limits that come from our being part of the natural world.

A minor reason why Auty, Donnelly and Ridley talk rubbish about Marx is that they never bother to read him. Ignorance is bliss when it’s folly to be wise. That ignorance did not begin with hacks for Mass Murdoch. In 1859, the learned ones ignored Marx’s 1859 Contribution to the critique of political economy. His only reviews of were both by Engels.

Undeterred, Marx pushed ahead and eight years later handed the manuscript of volume one of Das Kapital over to his Hamburg publisher.

Marx was so pissed off at the neglect of his earlier work that he quoted himself in the opening sentence to Capital. Again silence – but not for long.

It has to be said that Marx had done himself no favours. Engels had not seen the draft until after the page proofs arrived. He was horrified to find that Marx had divided its 784 printed pages into a mere six chapters. When Marx prepared a French translation in 1873, he divided the six chapters into 33. And he moved much of the documentation into ten Appendices at the back. The Moscow and Penguin translations both have 33 chapters.

But the bulk of his examples and evidence remains in those chapters. Capital might have a much wider readership if an English translation of the French edition were available.

We also need an edition which follows contemporary conventions about what constitutes a paragraph and what constitutes a sentence. There are too many parenthetical clauses, and too few full-stops. And I’d add a lot more section breaks and sub-headings. There is a student’s edition which removed the Greek quotations etc. I’m told the Chinese edition cut out the jokes as untranslatable. I hear that several other non-European translations have done the same.

There’s no point in wishing for an edition that we aren’t likely to get. We have to make do with what we’ve got.

And even with the most approachable edition imaginable, Capital is hard work. Marx set himself the almost impossible task of presenting the inner dynamics of a system which has to keep changing to survive. To present a snapshot of capitalism in 1867 was not to depict the structured dynamics that had led capitalism to that point. All is historical, that is to say, transient. Nothing stays the same. Small wonder that Marx’s favourite term is ‘metamorphosis’ – tadpoles turning into frogs.

Reading Capital is not too hard – if all you do is skim. There’s a joke about someone who did a speed-reading course. They then read War and Peace. When asked what it was about they replied: ‘Russia’.

That’s what many people do with Capital, including a lot of people who think of themselves as Marxists and as scholars. There is only one way to read Capital and that is slowly, carefully – and more than once. To give one example from our reading group in Canberra. We’ve just spent four hours on the thirteen pages of chapter 17 in volume one. Our sixteen-page explication of the chapter is on our group’s Facebook page.

Here’s another analogy in favour of taking our time. There are 28-day package tours of 20 European countries. What will you experience if you buy into one? Lots of airports, train stations, bus depots and hotel foyers.

What’s the alternative? You fly to Rome, book into a cheap hotel and spend your month walking the streets. You won’t have ridden the Paris Metro and you will have missed out on the Flughaven in Frankfort. But you will have some sense of what it means to say that Rome is still a work in progress. So is capitalism and – therefore – so is Marxism.

One alternative to skim-reading is to rely on a crib such as David Harvey’s Companion, or his video lectures. Two objections arise here.

First, the best ‘cribs’ are by Marx and Engels. Start from three shorter works by Marx: Wage-labour and Capital; Value, Price and Profit and Critique of the Gotha Programme. And two by Engels on The Housing Question and Socialism, Utopian and Scientific. The last named has convinced more people of Marxist socialism than any other single work. If you re-read those five pamphlets you’ll be off to a flying start.

But eventually we have to starting reading Capital itself. We can’t learn to swim without getting into the water.

Now for Harvey’s two Companions. I’ve never been enthusiastic about his treatments of Marx or of capitalism. But the low point came on New Year’s Day as we were driving back to Canberra from Melbourne. I had picked up a remaindered copy of Harvey’s Companion to volume two for $6.

Somewhere between Gundagai and the Yass turnoff, to break the monotony of the Hume Highway, I opened the Harvey. The opening paragraph made me so furious that I was about to chuck the Companion out the car window. What stopped me was the need the full text of Harvey’s rolling howler.

Harvey is far more misleading than I had imagined possible. Here is the offending sentence:

This commodity is then … sold for the initial amount of money plus a profit (or, as Marx prefers to call it, a surplus value.)

Wrongedy, wrongedy, wrong!

‘Profit’ comes out of ‘surplus value’ if the commodity is sold. Profit is not the same thing by another name. Surplus-value is added in the production process, not during circulation process. The relationship between surplus-value and profit is not a matter of preference – not Marx’s or anyone else’s. That much should be clear from volume one. Gawd help anyone who relies on Harvey’s Companion to that volume.

Why are we taking time this year to talk about Capital? 2017 is a doubly appropriate year to start studying it. September will be the 150th anniversary of its publication. November is the 100th of the Bolshevik revolution. May next year will the 200th anniversary of Marx’s birth. Those three dates will mean a lot more books and chatter about Marx, about Capital and about Marxism. So it will be more important than ever to be armed against the lies and distortions that have been going on for more than 150 years.

We began by mentioning that the attacks on Marx have flared again from The Australian. There is nothing surprising there. The only surprise will be if they don’t intensify between now and May next year. That would be alarming.

There’s a particular reason why the attacks are more intense in 2017 than they would have been only 10 years ago at the start of 2007.

That reason is the other theme of our sessions on Solidarity Breakfast: the on-going implosion in the expansion of capital which began to break the surface ten years back. That immediate financial crisis sent lots of people back to studying Capital. After all, crises are central to Marx’s analysis of how capital expands.

The agents of capital are short-sighted about many aspects of the system they are paid to defend. But they are not blind to its more powerful and perceptive critic. Were The Australian and its ilk not stepping up their attacks, we would have something to worry about. The fact that they are coming up with new ‘alternative facts’ about Marx and about Capital is encouraging to we Marxist dinosaurs.

Indeed, let’s conclude with a word in praise of dinosaurs. They came in all shapes and sizes and were all the colours of the rainbow. They lasted 26 million years. It took a vast meteor to wipe them out. Except that they weren’t made extinct. They were already evolving into birds and persist as crocodiles. Compared with their record, homo sapiens, capitalism and Marxism can be said hardly to rate, can we? No human invention is going to evolve for more than 26 million years.

Oh, to be a dinosaur.