by Brett Edgington – Ballarat Trades Hall Secretary

I acknowledge that this land was stolen from the Wathawurrung People of the Great Kulin Nation, never ceded. Always was, always will be Aboriginal Land.

I would like to thank sister Elisa and the parishioners of St Paul’s for their generous hospitality, the Advocacy at St Paul’s group and to those assisting with this evening’s service.

It is so important to us that this event has become an annual fixture for the future, to continue to highlight the importance of the Charter.

I acknowledge today, on the 11th that it is also the anniversary of Armistice Day and the day that the Whitlam Government was overthrown in a coup – maintain the rage Comrades!

Spring into summer of 54 had seen strange weather, sudden fierce thunder, and rain events. One such rain event interrupted the march to the Eureka lead for the Creswick crew, singing ‘La Marseillaise’ behind their German om-pa band, after George Black had rode to Creswick with a call to arms.

A squally northerly wind had fanned the flames that claimed Bentley’s Eureka Hotel for the Diggers – screaming for justice after the callous and almost casual murder of one of their mates – James Scobie allegedly covered up by the Camp.

The arrest of Gregorius, the Armenian servant of Father Smyth the Catholic Priest from St Alipius for not having a licence got the Irish particularly hot under the collar.

Surface alluvial gold was all but gone, deep leads were sunk chasing the ancient rivers – back-breaking digging week after week – but for months they had all bottomed out. Frustration grew with the sweltering heat – all the while the north wind threatened.

The British Empire had for years sent their best and brightest revolutionaries, thinkers, and progressives to Australia or to the gallows. Civil war and wars of independence had swept the Americas and much of Europe in the last few decades, leading to a diaspora of dispossessed fighters for liberty.

Many of these unlikely and ragged band of ‘misfits’ found their way to the goldfields, lured by the promise of wealth.

Lying under the night sky in their patch of mud on Ballarat, surrounded by forests stretching away forever and staring up to the Southern Cross and the Milky Way stretching from horizon to horizon, freedom must never have felt closer in this strange vast land.

And with the gold beneath their feet, emancipation was only a shovel full of dirt away. But so to was poverty, hunger and despair for the vast majority –even just eking out a living was tough for the many.

Up on the Hill, initially at Golden Point, and then at the Camp on the city hill – the neat, fenced compound of the troopers and soldiers served as a brutal visual reminder of the hand of the British Empire, the rigid class structures and deadly force used to retain order and to protect the world of the cashed up and classed elites with their ribbons, lace and fancy titles. And all the while regardless of their luck, the Diggers, Storekeepers and even non-miners paid the dreaded license fee or got dragged at the point of a bayonet to the logs to be chained, charged, and fined five pounds or more.

Down in the diggings, in the mud, class was forgotten, and people judged by their ability and willingness for hard work and sweat. In the flimsy canvas tents accountants shared with convicts, engineers shared with unemployed laborers – they shared the work and the rewards, and fierce friendships were forged in the tight shafts dug of equal measures of hope and despair.

This explosive mix of rebels, thinkers and war weary refugees on Ballarat ignited, and to the Chartists like John Basson Humffray, George Black and Henry Holyoake the words of the peoples Charter once again started to swim in their minds and their hearts as they saw injustice and brutality sanctioned from the highest levels of government.

Archie from Jones’s Circus on Main Road prophetically wrote 12 months before in the summer of 1853 – “The tents, theatres, bowling alleys, dancing saloons and hotels, all filled with a noisy, rough, restless crowd, feverish with the excitement of the great battle with the earth for her treasures, and the feeling that something was going to happen. There was a general presentiment of impending danger. It was, to use a hackneyed simile, as if we were sleeping over a volcano that we knew must, sooner or later, burst forth.”

Hotham, the very new Governor of Victoria – a military man, was spoiling for a fight; to put these colonials in their place. But he must have felt a twinge of terror on some sweltering still nights at Toorak as to how far the line of gold and silver lace of his officers was stretched – backup and the crown were a long, long way away.

Back in Ballarat, looking across the flat to this place and 10,000 Diggers from the camp must have chilled Commissioner Reid to the bone on this day in 54.

Many of these Diggers, a highly mobile population that chased the next ‘strike’ around the golden triangle, had been veterans of the meetings in Chewton and Mt Alexander, veterans of the Bendigo Red Ribbon Petition – that had seen a proposed doubling and expanding the mining tax proposed by Hotham and the Council defeated earlier in the year. They had tasted success and victory and seen the fruits of collective action against the colonial government come to fruition in dribs and drabs.

Reid, the Ballarat gold Commissioner was willing to be the crushing fist to stop the dribs and drabs – to put this unruly demanding mob in their place in the ranks – right at the bottom and at his and his officers will.

Ultimately it was Reid’s overreach – ordering a digger hunt the day after the 29th of November Monster Meeting at this place, collecting licences at the point of the bayonet from furious Diggers, many of whom he knew had burned them the night before – that made the bloody events of the morning of the 3rd of December inevitable.

These men of silver and gold lace conspired to win the battle – but ultimately, they lost their place in the order, as democracy took their power and prestige and consigned them to being servants of the public rather than the rulers.

The power they craved, those military men, slipped through their fingers the next year like the blood that flowed into the dust as the last of the soldiers and police scaled the ill prepared stockade on the morning of December the 3rd. At the end of the Eureka trials – 13 charged with Treason, all exonerated.

The added sting of seeing the rebel leaders including Humffray and Lalor elected over them to Parliament and the likes of Carboni to the courts in 1856 must have been all too much to bear in this new order of things.

Such an air of inevitability hung over the goldfields – like the dry bush in 54 waiting for the spark – breaking lose all hell.

“By and by there was a result, and I think it may be called the finest thing in Australasian history. It was a revolution – small in size; but great politically; it was a strike for liberty, a struggle for principle, a stand against injustice and oppression…. It is another instance of a victory won by a lost battle.” Mark Twain was to later describe it.

The 3rd of December saw the explosion – But this date the 11th of November – this date is important!

On the 11th November 1854, on this site in the afternoon, one of the most significant events in the post colonization history of Australia took place. On this date, a meeting of Diggers, led by the members of the Ballarat Reform League, read, and adopted the Ballarat Reform League Charter.

The ‘Charter’ has formed the basis of Australia’s democratic system that we know today, leading to the enfranchisement of the vote for working men and later women and eventually for our Aboriginal sisters and brothers.

The ‘Charter’ formed the basis and language for our modern parliamentary system, enforcing the basic underlying tenant that “it is the inalienable right of every citizen to have a voice in making the laws he is [they are] called upon to obey.”

In terms of the legacy of Eureka, eminent historian the late Professor John Molony said, “The influence of the Ballarat Reform League Charter on the development of Australian democracy was decisive. The constitutions of all the 19th-century Australian colonies, which later became the states that formed the Australian Commonwealth in 1901, contained the fundamental rights outlined in the Ballarat Reform League Charter, as did the Constitution of the Commonwealth itself.”

Up until the early 20th Century Australia led the world in modern democratic reform all because of the adoption of the ‘Charter’ here on Bakery Hill on the 11th of November 1854. The ‘Charter’ not only shaped Australian society, but it also had vast ramifications for democratic reform across the globe.

The ‘Charter’, just 12 months later in 1855, led to representatives of working people without land qualifications from Ballarat elected to the first Victorian Legislative Assembly. Lalor and Humffray were elected along with other representatives of Victorian goldfields.

Further significant meetings on Bakery Hill from the 29th of November 1854, also led to the events surrounding the construction of a stockade on the Eureka Lead and saw the ‘flag of the Southern Cross’ unfurled as the first Australian flag, (not the Union Jack) to which Australians swore an oath of allegiance.

Whilst the importance of the site of the Eureka Stockade on the Eureka Lead can never be disputed, it can be argued that the ‘Charter’ adopted at Bakery Hill had far more wide-reaching and ongoing significance for Australian democracy.

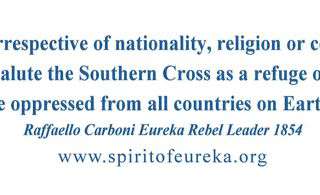

The raising of the flag of the Southern Cross on Bakery Hill also introduced a symbol to our nation of incalculable importance for our past and future. In the words of an eyewitness and contributor to the Bakery Hill meetings, Raffaello Carboni, I call upon all miners “irrespective of nationality, religion or colour to salute the Southern Cross as a refuge of all the oppressed from all countries on Earth.”

Events surrounding Bakery Hill and the Eureka Lead also led to the formation of the organised Labour Movement in Australia in 1856, (starting in Melbourne and Ballarat) our Council, its predecessor in the Eight Hour Committee and the Early Closing Association and our Hall in Camp Street led to the formation of the Modern Union Movement.

These events also shaped the global growth and character of organised Labour. It is for this reason why we take a strong interest in this site and this date which is of profound importance to our movement.

Jenny Beacham from Fed Uni, a PHD Student writing the History of our Trades Hall recently uncovered an article in the Melbourne Age newspaper from 1856 that showed only eight days after the stonemasons marched in Melbourne on the 21st April starting our Australian Labour movement, that an advertised meeting took place in Ballarat on the 29th April, chaired by James Oddie Mayor of Ballarat held here on Bakery Hill establishing a Ballarat Eight Hour Committee. This was only 17 months on from Eureka.

No doubt that the Eureka events laid the foundations and created the atmosphere that saw working people stand up in the Colony of Victoria and demand their equitable share of the wealth they created.

The story of Eureka – the massacre, was not the end but the beginning of a story that remains unfinished to this day – a story that encompasses the creation of our democratic systems, the formation of our Labour movement and the development of Australia’s unique way of life with its fair go for all.

Remaining, is the call of the Charter – that if their voice was to be ignored, they might cause separation from the Mother Country and the creation of a new Australian Republic.

Henry Seekamp, the editor of the Ballarat times whose office was also located not far from here on Bakery Hill wrote in 54, “This league is nothing more or less than the germ of Australian independence. The die is cast and fate has stamped upon the movement its indelible signature. No power on earth can now restrain the united might and headlong strider for freedom of the people of this country and we are lost in amazement while contemplating the dazzling Panorama of the Australian future.”

It was never the intention of the League on this day in 1854 for diggers to end up behind a stockade on the morning of the 3rd – the plan was to establish a large tent in the East as a Headquarters for the league, that members pay a subscription to join – that the Flag of the League was to be flown over the headquarters and that by petition and democratic means change would be achieved.

History records however that physical force overtook the moral force – “Moral persuasion’s all humbug, there’s nothing convinces like a lick in the lug!” said Tom Kennedy of the League after frequent goading by the gold and silver lace from the camp.

Eureka was not the end but the beginning of a story, one that was written and adopted here in this place, thousands of miles away from the seat of Colonial Power, the words of the Peoples Charter, carried as a burning torch in the hearts of the British Chartists of the 1840s were once again committed to paper and popular vote in the back room of the Star Hotel on Main Road and on this Hill, the greatest fears of the Empire were realized – liberty was writhing to break free.

This evening we give thanks to those Diggers who took a stand for liberty – many of whom sacrificed their lives so that we can live today in the Australia we do. And we remember the threads of revolution, the dangerous words of sedition, liberty, and justice – that came together at this place to pull tight and weave a new Australian future. We pay our respects to the men and women who died at Eureka and to the moral forces that continued the fight after blood was spilled, continuing to petition and pressure for change.

We acknowledge John Basson Humffray – the Secretary of the Ballarat Reform League who, as the author of this Charter document should be recognized in this country as akin to the US authors of their Declaration of Independence – Humffray died a pauper after his parliamentary career and always demanded he be buried alongside the Eureka Diggers – his wish was granted, and a public subscription saw his grave suitably recognized.

We trust in this 168th year that we might eventually realize Ballarat Times Editor Henry Seekamp’s new ‘Australian congress’ and the ‘dazzling panorama of Australia’s future’ and that the seed planted at the Star Hotel and here on Bakery Hill might continue to grow – tended by our next generations of rebels, thinkers, and activists.