by Richard Stone

A major diplomatic statement at a regional defence summit has revealed US-led military planning for a sensitive area of the South China Seas, an area of the Indo-Pacific region regarded by the Pentagon as a ‘theatre of war’. The significance of the South China Seas has been raised by the US in recent years following China emerging as a credible competitor to the traditional regional US hegemonic position. The diplomatic statement, however, has to be viewed in the context of wider regional developments for accurate assessments.

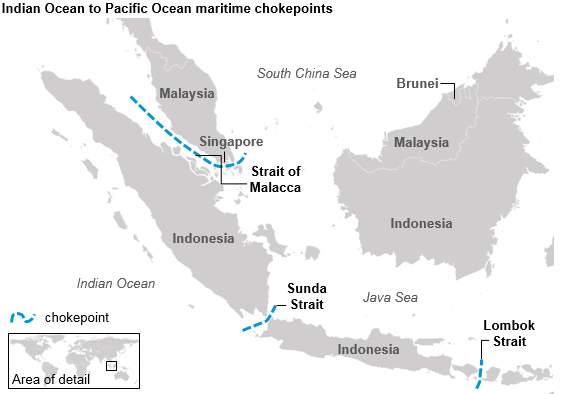

At the Singapore-hosted Shangri-La Dialogue last month, Indonesian defence minister Prabowo Subianto issued a high-level diplomatic statement about concerns arising over three strategic waterways: Indonesia controls the Sunda and Lombok Straits and co-manages the Malacca Straits with Malaysia. (1) The three waterways are used by thousands of vessels each year and fears have arisen about their defence and security amid rising US-led tensions across the wider Indo-Pacific region. Prabowo Subianto drew attention to the previous decades of relative peace and stability in south-east Asia, and that following developments elsewhere senior US, Australian and Japanese military officials had recently warned about fears of blockades in the South China Seas. (2) The present Indonesian governments fears being drawn into a super-power conflict between the US and China, within its waterways.

The diplomatic statement followed disclosures that the US had actually planned to ‘close the Strait of Malacca in the event of a conflict with China’. (3) The military plan, conducted with the so-called Quad consisting together with Australian, Japan and India, has met with concerns across south-east Asia: many countries in the region have strong links with China. It has led Indonesia, for example, to lobby the ASEAN Outlook group to ‘promote a more inclusive approach to regional maritime domain that does not seek to alienate China’. (4)

The US, however, appear intent upon using ASEAN for their own interests, which have recently included US president Joe Biden using a two-day summit in Washington to ‘focus heavily on China’s influence in the region’. (5) An impasse is taking place: while the US has continued to push their own diplomatic position upon the region, it has been noted ‘ASEAN

nations have made clear they do not want to take sides in the escalating power fight between Beijing and Washington’. (6) To the contrary, most ASEAN countries are happy to improve their trade ties with China and have openly criticised ‘Washington’s largely security-focused approach’. (7)

It is not particularly difficult to establish the US defence and security focus on China, and their planning to raise diplomatic tensions at every opportunity. While the US appear to be losing the economic edge against China, the military option has been placed higher up their diplomatic agendas.

In mid-July China drove a US war-ship away from what Beijing claims is their territorial waters in the South China Seas. The US had sailed the Benfold, a guided missile destroyer on a ‘freedom of navigation mission’ close to the Paracel Islands. (8) Later, a similar mission with the USS Ronald Reagan was seen to be performing a security operation in the area. (9)

Earlier operations started in January; 2022 has seen almost continual series of diplomatic stand-offs in the South China Seas.

The US-led military options against China lie in diplomatic decisions taken over a decade ago with Pentagon planning. During the Obama presidential period, high-level diplomatic initiatives were responsible for re-opening military facilities across the Indo-Pacific region: they were, invariably, conducted on the basis of US presence in hosted bases. Gone were the days of large-scale US military bases, operating as small cities in foreign countries. The preferred option was for smaller-scale facilities. (10)

In the Philippines, for example, the US military operate from five facilities hosted by the Philippine military forces. The five facilities, however, remain off-limits to all Filipinos, whether military officials or civilians. (11) The US military presence has, nevertheless, included joint exercises with their Philippine counterparts. One exercise, involved 1,400 US troops supposedly training only five hundred Filipino soldiers in amphibious landing drills in Palawan and other coastal areas of Luzon. (12) So much for one-to-one supervison.

When US vice-president Kamala Harris addressed the recent Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) in Suva, the list of new US projections into the region included two new embassies in Tonga and Kiribati, Peace Corps aid workers to assist with US-planned ‘development programs’, a new US envoy to the PIF, and a US$600 million program for development of fisheries. (13) Under US diplomatic pressure, the PIF also excluded Chinese diplomats from attending the forum even as a dialogue partners.

The fact that Tonga and Kiribati exist on an arc from sensitive Australian military facilities in Queensland and include the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Tuvalu, Fiji and Western Samoa and other smaller landmasses inside the triangulation, would tend to reveal the existence of US electronic warfare facilities inside their embassies. (14)

The US military initiatives, however, remain peripheral when judged against other, more pressing, considerations. If the primary goal of Washington is to build a coalition across the region against China, they will remain sorely disappointed. The ASEAN countries, for example, recently signed a regional trade deal with China. It has also been noted Australia, as the main hub for ‘US interests’ in the southern part of the region, has more investment in New Zealand than in all the ten ASEAN countries. (15)

When Indonesian defence minister Probowo Subianto took the rostrum at the Shangri-La Dialogue to raise concerns about the three strategic waterways his government controls, it was really a warning to the US and their allies that countries strongly associated with regional diplomatic organisations have no wish to be drawn into US-China rivalries. It is best viewed in the following context: while the US seek to reassert traditional hegemonic positions by using diplomatic tactics reminiscent of the previous Cold War, the countries of ASEAN have moved on and made better use of trade links with China for their own benefit. Decision-makers in Canberra, seemingly only confident when blinkered and following US-led directives, might consider taking note of some of these recent developments!

1. Global tension sparks ‘line of fire’ warning,

The Australian, 29 June 2022.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Biden pledges funds to reset ASEAN ties,

The Weekend Australian, 14-15 May 2022.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Beijing bristles at US ship’s South China Sea mission,

The Australian, 15 July 2022.

9. Ibid.

10. See: US eyes return to south-east Asian bases,

The Guardian Weekly (U.K.), 29 June 2012, and,

US signs defence deal in Asia,

The Guardian Weekly (U.K.), 2 May 2014.

11. See: Tightening Phl military involvement with the US,

The Philippine Star, 5 May 2018.

12. Ibid.

13. Countering China’s influence at the Pacific forum,

The Weekend Australian, 16-17 July 2022.

14. See: Map of the World, Peters Projection, Actual Size.

15. Re-engaging in the politics of being a good neighbour,

The Weekend Australian, 16-17 July 2022.