by Don Longo

Carboni and Gilburnia

Raffaello Carboni is known to Australians as one of the leaders of the Eureka rebellion and the author of the only complete eye-witness account of the dramatic events that unfolded at Ballarat in late 1854. Other aspects of his eventful and restless life are less remembered, such as his activity as a republican revolutionary in Italy in the 1840s, his wanderings across Europe, Asia and the Middle East, his work among Garibaldi’s Red Shirts and the Expedition of the Thousand in the 1860s. He also struggled to be recognised as a writer in Italy after he left Australia in 1856 until his death in Rome in October 1874, alone and penniless, aged 57.

Raffaello Carboni is known to Australians as one of the leaders of the Eureka rebellion and the author of the only complete eye-witness account of the dramatic events that unfolded at Ballarat in late 1854. Other aspects of his eventful and restless life are less remembered, such as his activity as a republican revolutionary in Italy in the 1840s, his wanderings across Europe, Asia and the Middle East, his work among Garibaldi’s Red Shirts and the Expedition of the Thousand in the 1860s. He also struggled to be recognised as a writer in Italy after he left Australia in 1856 until his death in Rome in October 1874, alone and penniless, aged 57.

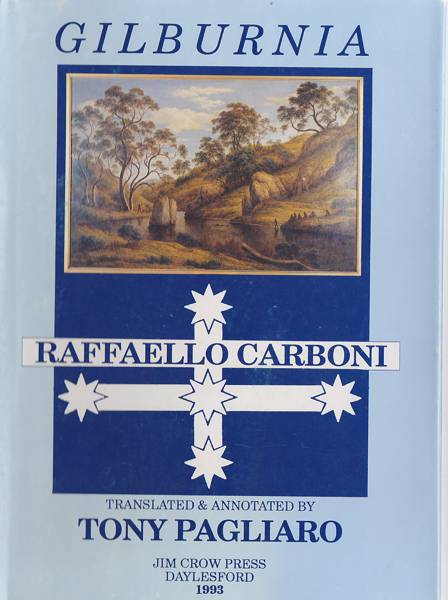

What are often ignored in Australia are his experiences among Victoria’s Aborigines and his subsequent reflections on the effects of British imperialism on their lives. It was in late 1853 that, after some unsuccessful attempts at finding gold and getting dysentery for his troubles, he decided to leave the goldfields and become a shepherd in the Loddon valley, near present-day Maldon. While there he ‘got among the blacks, the whole Tarrang tribe in corrobory’, as he puts it, observing the customs and language of the Djadjawurrung tribe around Bendigo, taking notes for an Italian-Aboriginal dictionary, and then ‘went to live’ with them for an unspecified period. He gave a brief account of this experience in the Eureka Stockade (chap. 5). He returned to this encounter and pondered over its meaning in a pantomime published in Italy in 1872, Gilburnia. It is the only other book on Australia published by Carboni.

This work is a story in itself. Thought for a long time to have been lost, a copy was ‘discovered’ on a Rome street stall by an academic at La Trobe University, Tony Pagliaro. He subsequently translated it into English and a dual language edition was published in 1993, which included Carboni’s dictionary, or ‘Antarctic Vocabulary’ as he called it.

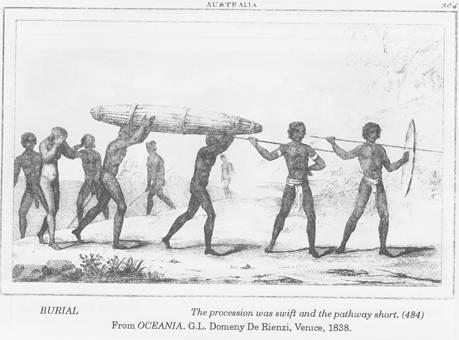

The publication has thrown new light not only on Carboni and the Eureka rebellion, but on the forgotten people in the Eureka story: the indigenous inhabitants of the goldfields. Since 1993, valuable research has been undertaken on the subject, in particular by Fred Cahir whose book (Black Gold: Aboriginal People on the Goldfields of Australia, 1850-1870. ANU Press, 2012) helps to put Carboni’s observations and reflections into a historical context. In a country where Aborigines are often invisible in narratives of its present and its past, and where there is seldom recognition that gold mining took place on Aboriginal land and that it disrupted forever the lives of the Indigenous inhabitants, these are welcome reminders of an unforgivable historical neglect.

The publication has thrown new light not only on Carboni and the Eureka rebellion, but on the forgotten people in the Eureka story: the indigenous inhabitants of the goldfields. Since 1993, valuable research has been undertaken on the subject, in particular by Fred Cahir whose book (Black Gold: Aboriginal People on the Goldfields of Australia, 1850-1870. ANU Press, 2012) helps to put Carboni’s observations and reflections into a historical context. In a country where Aborigines are often invisible in narratives of its present and its past, and where there is seldom recognition that gold mining took place on Aboriginal land and that it disrupted forever the lives of the Indigenous inhabitants, these are welcome reminders of an unforgivable historical neglect.

Giburnia, The Pantomine

Gilburnia (with the ‘G’ pronounced in the Italian fashion, like the English ‘J’) was written as a pantomime, a sort of theatrical ballet. Carboni meant it to be a stage performance without dialogue mostly relying, as pantomimes do, on movement and gesture, dance and acrobatics to deliver the plot and message. The text that has survived includes no stage directions, so it is difficult to picture how Carboni might have imagined the action. It probably included a musical accompaniment of some sort, though we have no information about what it might have entailed. Its 804 lines of text were written in terza rima in imitation of Dante. Most likely, they would have been declaimed from the sidelines during the performance to give the movements on stage context and meaning. It is unknown whether it was ever performed.

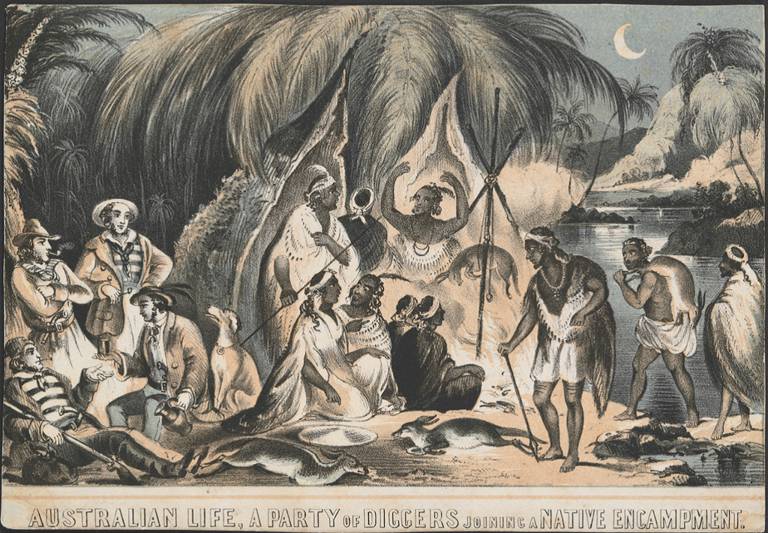

Its plot is relatively straightforward, though Carboni introduces concurrent events in the narrative which introduce some complexity. It is the story of Gilburnia, the daughter of a tribal elder in the Loddon valley, whose grace and beauty is such that she is wooed by two strong and brave men of the tribe, Boom and Rang, through a ritual battle. Mayhem ensues, however, when a group of drunken and lascivious gold miners invade the tribe’s territory and kidnap Gilburnia who is then threatened with gang rape. The miners’ leader, Gruno, decides that he wants her for himself, but she manages to escape into the forest. Meanwhile, her tribe attempts to save her and follows the kidnappers, but Gruno’s companions massacre most of them at night while asleep at a water-hole. Gilburnia makes it back to her father, but is followed by Gruno who is himself killed by Rang, Gilburnia’s suitor. The colonial police arrive and arrest the Aboriginal survivors, who are condemned for the murder of the miners’ leader by a corrupt judge. At the last minute, there is a hurricane that destroys the court allowing the Aborigines to go free. Everything returns to harmony and justice prevails.

Its plot is relatively straightforward, though Carboni introduces concurrent events in the narrative which introduce some complexity. It is the story of Gilburnia, the daughter of a tribal elder in the Loddon valley, whose grace and beauty is such that she is wooed by two strong and brave men of the tribe, Boom and Rang, through a ritual battle. Mayhem ensues, however, when a group of drunken and lascivious gold miners invade the tribe’s territory and kidnap Gilburnia who is then threatened with gang rape. The miners’ leader, Gruno, decides that he wants her for himself, but she manages to escape into the forest. Meanwhile, her tribe attempts to save her and follows the kidnappers, but Gruno’s companions massacre most of them at night while asleep at a water-hole. Gilburnia makes it back to her father, but is followed by Gruno who is himself killed by Rang, Gilburnia’s suitor. The colonial police arrive and arrest the Aboriginal survivors, who are condemned for the murder of the miners’ leader by a corrupt judge. At the last minute, there is a hurricane that destroys the court allowing the Aborigines to go free. Everything returns to harmony and justice prevails.

Gilburnia also includes an opening ‘Antarctic vocabulary’ of Aboriginal words translated into Italian, compiled during the time he lived with the Aborigines, in December 1853-January 1854. People have criticised this for its inaccuracies, and to be sure they are there; but the fact that it is compiled at all is meaningful, since few at the time considered Aboriginal languages to have any worth let alone giving them European renderings.

Themes

Carboni uses the literary devices afforded by Gilburnia to expose the dispossession of the Aborigines and the effect the loss of land and freedom had on them. Carboni’s miners, unlike those of the Eureka Stockade, are materialistic and savage. They are embodiments of ‘evil’ and driven by ‘blood’, coming into the Aboriginal camp with cutlasses and pistols, all of them ‘white rabble’ characterised by ‘full moon belly, red nose and hunting dog’s snout’ and the ‘look of hungry she-wolves’ in their eyes. Carboni recognises the intoxicating lure of gold which drives them to defy death itself, but acknowledges that this is self-defeating, as many do indeed die underground in their greed. He mocks them for thinking of gold as ‘always the Alpha and Omega’, imagining themselves ‘respectable gentlemen’ because of their wealth while remaining ‘pirates and brigands’ addicted to liquor. Gold is Mammon, though ‘sweet [be] the burden of its chain’.

Opposed to the values reflected by the miners are the Aborigines. They are noble savages ‘singing and dancing together’, free of clothes and shame, sleeping ‘without counting the stars’ and with ‘no boss or slave-driver’, content to just ‘eat just [their] fill’ rather than gorge themselves or kill for sport. They live in an Arcadia without stain or sin, in a superb landscape of birds, sunshine, ‘joy and happiness’. Or rather, a disappearing Arcadia, since Carboni is aware of the Aborigines’ own growing corruption, telling us that they are being taught to love ‘Mammon’ by the whites.

Opposed to the values reflected by the miners are the Aborigines. They are noble savages ‘singing and dancing together’, free of clothes and shame, sleeping ‘without counting the stars’ and with ‘no boss or slave-driver’, content to just ‘eat just [their] fill’ rather than gorge themselves or kill for sport. They live in an Arcadia without stain or sin, in a superb landscape of birds, sunshine, ‘joy and happiness’. Or rather, a disappearing Arcadia, since Carboni is aware of the Aborigines’ own growing corruption, telling us that they are being taught to love ‘Mammon’ by the whites.

Carboni goes further than just opposing two different value systems: a keen observer and social critic, he highlights how the colony used British law to justify the dispossession and destruction of Australia’s indigenous inhabitants. He ultimately rejects any faith in British justice: Gilburnia’s judge is incompetent and in league with the dispossessors, he is ‘a skeleton of tired virtue’ who loves the death penalty, that ‘ancient glory of his country’ [i.e. Britain]. Indeed, British justice even fails to understand its own act of dispossession: ‘the black race’, says a miner to the judge in disbelief, ‘disowned by Noah, thinks we stole its land!’ Writing in the middle of the 19th century, Carboni’s position was prescient and revolutionary.

No less so was Carboni’s examination of the role of women both in indigenous and European culture, where they are seen and treated as little more than chattels. In the pantomime, Gilburnia challenges this proposition. She is strong and fearless, will not obey the man she is supposed to marry despite tribal law, and in the plot she remains an active agent of her own destiny, be it in her tribe or the hands of the miners.

Meanings

Pagliaro sees Gilburnia as a retelling of the Eureka Stockade events through metaphor and allusion. I don’t agree. Gilburnia is not a retelling of the rebellion at Ballarat but, in literary form, of the political principles that underpinned it transferred to the broader canvass of British colonialism and its effects on the colonised. As a revolutionary in the European tradition of 1848, Carboni tells us in Gilburnia that human rights are universal and timeless irrespective of place and race, that imperialism is the philosophy of the white man which says that ‘might is right’, that imperial law is the hand-maiden of power. True to his values, Carboni leaves us in no ambiguity: tyranny must be resisted everywhere since has an insatiable appetite; yesterday it only wanted ‘your money or your life’ he laments, while today it wants ‘your money and your life’ [italics added].

Carboni also recasts the 1848 debate about the meaning of democracy by linking it to colonialism’s erosion of Aboriginal, not miners’ rights. In this way, the development of Australian society, the growth of its wealth, indeed the progress toward self-government in the Australian colonies is linked to abuses towards Aboriginal people and to their dispossession. And perhaps, though here I speculate, Carboni is reviewing the outcomes of the Eureka rebellion, showing that the miners are imitating, by their treatment of the Aborigines, the abuses of the authority they had themselves rebelled against a generation earlier.

Legacies

In Gilburnia, Carboni continues to surprise us with the daring of his ideas. Although odd as a literary genre, the pantomime restates the progressive ideas of a mid-19th century revolutionary and applies them to British imperialism and to its devastating effects on the indigenous inhabitants. Again he challenges facile interpretations of the power struggles in colonial Australia, between the miners, the Empire and the Aborigines, and between men and women. His language is eccentric, but it is always sincere in its defence of the underdog, its abhorrence of oppression and tyranny in all its forms. His lesson is always the same: that we should not concede on principle, never give in, and stay true to the Eureka oath.

In Gilburnia, Carboni continues to surprise us with the daring of his ideas. Although odd as a literary genre, the pantomime restates the progressive ideas of a mid-19th century revolutionary and applies them to British imperialism and to its devastating effects on the indigenous inhabitants. Again he challenges facile interpretations of the power struggles in colonial Australia, between the miners, the Empire and the Aborigines, and between men and women. His language is eccentric, but it is always sincere in its defence of the underdog, its abhorrence of oppression and tyranny in all its forms. His lesson is always the same: that we should not concede on principle, never give in, and stay true to the Eureka oath.

Raffaello Carboni. Gilburnia: Pantomime in Eight Scenes with Prologue and Moral. Edited and translated by Tony Pagliaro. Melbourne: Jim Crow Press, 1993. 140 pages with illustrations & facsimile of the 1872 original hard cover. Available from the Daylesford and District Historical Society, Price: $27.50 plus $4 postage and packaging. [http://www.daylesfordhistory.com.au/publications.htm].