by Dr Don Longo

by Dr Don Longo

Sometimes a joke turns into fact, and what started as light comedy turns into profound tragedy. This is the case with the Australian Labor Party and its much-flaunted ‘new way’.

The joke was prevalent in the 1980s. Labor, it was said, had moved so far to the right of politics under the stewardship of Hawke and Keating that the acronym of ALP really stood for the Alternative Liberal Party. The tragedy is that this is precisely what a new generation of in the ALP is now claiming.

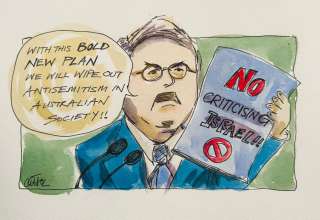

Bowen’s blueprint and Labor’s ‘new way’

Treasurer Chris Bowen’s recent book, Hearts and Minds: A Blueprint for Modern Labor (MUP, 2013) proclaims with unambiguous pride that the ALP is indeed Australia’s ‘truly liberal party’. This ‘blueprint’ goes back to Labor’s initial term under Rudd, and was first sketched in a lecture given at the business community’s Sydney Institute in 2008 (The Sydney Papers, Spring 2008, 148-156). A number of other Labor MPs, notably the member for Fraser, Andrew Leigh, have been enthusiastically promoting the same idea for some time (http://australianpolitics.com/2012/12/05/on-labor-and-liberalism-leigh-glover.html). It is Labor’s ‘new way’.

Bowen’s and Leigh’s intention is to re-create Labor as a ‘modern’ political party by giving it a new philosophy to guide policy development. Unfortunately, this new philosophy is actually not new at all: it is small ’l’ liberalism, or ‘social liberalism’. The roots of this ‘new way’ do not draw sustenance from Labor’s past element of social democracy, still less from the founders of socialism. Rather, they draw from the tradition of the British Liberal Party, from John Stuart Mill and Jeremy Bentham, from British Fabians and Chartists, from English late 19th and early 20th century English political figures such as Asquith, Lloyd George and Keynes. The aim is to build on the ‘economic reforms’ of the 1980s, those of Hawke and Keating, and extend them into the 21st century. In this context, Bowen’s ‘new’ ALP is ‘the party of the individual’ since it protects a person’s rights against social interference and ‘celebrate[s] the individual’ through political, economic and social freedom. It is ‘the party of economic growth’ since it is committed trade liberalisation and micro-economic policy. It is ‘the party of small business’ since it ensures business opportunity and promotes competition. It is about the ‘powers and benefits’ and the ‘vigorous operation’ of free markets, including the market for of the modern finance industry. It is about the government as manager of capital, acting as the safety net for any ‘market failures’. It is the party of ‘social justice’ insofar as it promotes ‘equality of opportunity’ through education and self-employment. Most of all, it is the party of continuous ‘economic growth’. Everything in this new liberal party depends on economic growth since its aim is not to end social inequalities but to give those at the bottom just a little more of the ever-increasing prosperity. Economic growth is everything.

This is the blueprint. It has more in common with Australian liberals such as Deakin and Menzies and Fraser, and certainly with Don Chipp, than social democrats like Chifley or traditional working class labour activists like Percy Brookfield. It has nothing to do with the socialism that still forms part of the Labor platform. Surprisingly, both Bowen and Leigh quote Lenin when, in 1913, he called the ALP disparagingly as a ‘liberal-bourgeois party’ (reproduced in E.F. Hill, Australia’s Revolution, 1973 – http://www.marxists.org/history/erol/australia/hill-a-rev/app-2.htm). Lenin was right, they say. The ALP is indeed Australia’s ‘truly liberal party’.

This transformation of social-democratic parties into small ‘l’ liberals is not unique to Australia. The same makeover took place in Britain during the blight of the Blair years and in the USA during Clinton. Until now, comparable parties in Europe have made concessions but have resisted the temptation to give in so totally as Bowen, and have yet to concede so much ground to privatised wealth and global capital.

What happened? How did it come to this?

Fukuyama’s liberal consensus and the end of history

The transformation reflects a broader change after the fall of the Soviet Union, particularly in countries with Anglo-Saxon institutions and traditions. It was described over 2 decades ago by an astute American academic, Francis Fukuyama, in The End of History and the Last Man (Penguin, 1992). The book is instructive. Fukuyama saw the end of the 20th century as the final ideological triumph of liberal values in both the political and economic spheres. After the fall of the Berlin Wall he says, there is a broad consensus about the legitimacy of liberal democracy as a system of government in the world, and its commitment to the twin values of ‘liberty’ and ‘equality’ within a capitalist economy constitute the ‘end point of man’s ideological evolution’, the ‘final form of human government’.

That is not to say that the implementation of this system is always perfect and further work will continue to improve on the liberal consensus; but any specific dysfunctions do not reflect on the system itself. Thus, all the big questions of history, all internal social contradictions and their ideological forms, have been resolved. Class no longer exists in this liberal utopia, because individuals relate directly with the state and employees directly with capital. Causes such as the environment, animal rights, gender issues, race and ethnicity, are trivialised or pushed to the periphery of the mainstream, as marginalia, dealt with through dominant liberal institutions that are henceforth unquestioned and unquestionable. The only significant issue is the economy. Economic growth is the new deity and consumerism the new faith. Wealth and the free market reign supreme in an ideological framework that is no longer contested. Political ideology has been settled. We are in the era of ‘the last man’. There are no more grand narratives, only events. Hegel’s prediction has finally been realised. It is the ‘end of history’.

Social liberalism and its illusions

Fukuyama’s book exposes the Emperor’s nakedness: Bowen’s ‘new way’ is at best an accommodation to the dominant political and economic frameworks, at worst a capitulation to them. Bowen’s Labor has given up the fight. It has given in.

Take its ‘liberalism’. Historically this has been the handmaiden of capitalism, and remains its favoured political framework. The reasons are easy to see. It maximises individual freedom and limits government interference. It ensures that individuals are egoistic and therefore good consumers; that they are atomised and therefore vulnerable. It protects private property and subordinates equality to the pursuit of ‘enlightened self-interest’, that is to say, private wealth and personal advancement are more important that community and social responsibility. ‘There is no ‘society’ and no ‘state’ said the neo-liberal Thatcher, only ‘individuals’ pursuing private profit.

Take its ‘equality’. Prosperity is never equal and is never shared equally in a free market. Bowen is right when he says that ‘economic growth’ will benefit everyone, rich and poor, capital and labour. But they will not all benefit to the same extent. Bowen ignores the increase in inequalities over the last 30 years despite a growing economy: it is true that the floor has been lifted, but it is also true that the ceiling has rocketed skywards for the rich and the profits of capital make the meagre increases to working families pale into insignificance. Bowen closes his eyes to the casualization of work, the unemployment, the dependence of low paid workers on government support, just as he is cavalier about the causes of the financial crisis. By focusing on growth, he can promise that everyone will get a bit more and hope that they won’t question the shameful distribution of the prosperity generated by that growth. The debacle over the mining tax is a case in point.

Take his ‘social justice’ and his ‘compassion’. There is no commitment to a welfare state and matters of solidarity are of minor importance, more implied that stated. His justice is a passive justice, that of equal opportunity, access to education, encouragement to self-employment. Bowen’s liberal party is capitalism with a just little heart for vulnerable Australians. However, the compassion, meagre as it is, stops at the nation’s borders since asylum seekers are not worthy of his attention.

Labor’s liberal ‘new way’ must be called what it is: a slipshod and superficial pragmatism to acquire and retain power within a liberal political consensus and a capitalist economic framework. In Labor there has been a century-old tension between social democracy on the one hand, and liberalism on the other. Bowen falls completely on the side of the latter. It is the culmination of the Hawke/Keating Accord of the early 1980s. It ignores the social structures that perpetuate inequalities and the fundamental problems with global capital and finance which were the cause the GFC. It focuses on rights instead of responsibilities, social tinkering rather than social change, patchwork justice instead of institutions and structures that promote community and social solidarity. Most of all, there is a lamentable loss of purpose in this new Labor: it is a ‘new way’ dominated by the language of statistical calculation, and what one Labor colleague (Dennis Glover) has called a ‘moral flatness’. Fukuyama already warned against this in 1992: the liberal consensus can lead to a consumerist, purposeless existence of ‘men without chests’, without grand vision or passion. When Fukuyama’s ‘last man’, the man of Bowen’s liberalism, reaches the light on the hill all he will find are the floodlights of Disney World. And he will be satisfied. This is Bowen’s vision for Labor. Therein lays the tragedy.

Lenin’s hope and the end of Labor

I do not believe that we at the ‘end of history’. Fukuyama was wrong. There are still barbarians at the gate, clamouring for alternatives to the complacent values of Labor’s ‘new way’, to free market capitalism and the lazy liberal consensus under the global tutelage of the USA. In 1913, Lenin was fascinated by the spectacular growth of Labor in Australia and believed that, as the new nation reached maturity, this ‘liberal-bourgeois party’ would ‘make way for a socialist Labor Party’. It is time for the unions and working people to abandon the ALP and put their support behind a new mass party, ‘a socialist Labor Party’ (emphasis added). The ALP is not what it used to be; it has truly become the Alternative Liberal Party. We are not witnessing the end of history but the end of Australia’s party of labour, the end of the Australian Labor Party.