By Richard Stone

Reviews of the recently declassified cabinet papers from the Howard coalition government twenty years ago in mainstream Australian media have tended to gloss over the significance of two closely related matters. Other related declassified material, already in the public domain, however, can be easily accessed to show how controversial matters have been down-played to enable Canberra to distance itself from what they regard as undue public scrutiny, with far-reaching implications for contemporary Australia.

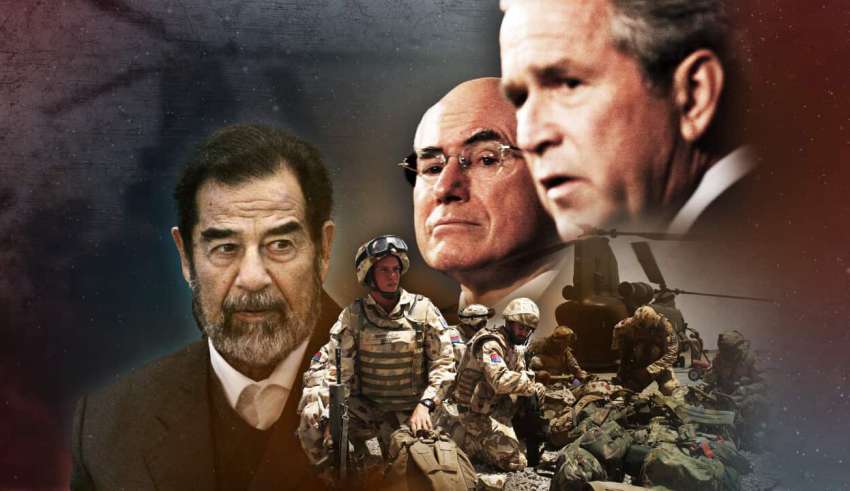

Two decades ago the Howard coalition government was part and parcel of the US-led military invasion of Iraq and its unfortunate aftermath. It followed the sycophantic nature of the Australian government of the day and its unquestioning acceptance of US military planning for the 2003 invasion. Resting upon deeply flawed intelligence assessments, it was noted to have ‘abjectly failed to achieve its central goals’, twenty years afterwards. (1)

While the US-led forces were quick to languish in their initial victory, any successes attached to the matter were soon to appear a debacle. A year after the initial invasion, then Defence Minister Robert Hill, had written a letter to Prime Minister John Howard which was subsequently shared with the National Security Committee (NSC), informing the cabinet ‘expressing optimism that Iraq could become a modern state that was a model for other countries in the Middle East with a free-market economy and pluralist society’. (2)

A year later, however, it was noted by Canberra that ‘the deteriorating security in Iraq … and … the situation in Iraq showed little prospect of improving’. (3)

The diplomatic position generally accepted in Canberra that, ‘the Americans handled the post-invasion phase of Iraq badly and of course they lost control of it’, was not widely publicised at the time. (4) Supporters of the so-called ‘alliance’ in Australia did not want unfavourable publicity about diplomatic relations with the US.

Subsequent studies of the US-led invasion of Iraq and its aftermath, however, have provided a mass of information about highly suspect planning and continued failure by the intelligence services to correctly assess the country in any meaningful manner. (5)

The studies have also drawn attention to the fact that Iraq, prior to the invasion, had been developing a biological and germ warfare arsenal; it was given little open publicity at the time although it had been already noted in official studies. (6) Can the lack of publicity be attributed to diplomatic silence? Or perhaps the US-led intelligence services were perhaps too busy: they were totally preoccupied with finding the ‘Weapons of Mass Destruction’. The philosophical issues and considerations about the very nature of their existence has continued to haunt them to the present day. It will do forever.

Almost hidden in this years declassified cabinet papers lies a decision taken by the Howard coalition government to introduce provision for dealing with pandemics, however, which has revealed their close working relations with the Pentagon.

Then health Minister, Tony Abbott, was noted in October, 2005, to have briefed the NSC

‘on pandemic preparedness and the risk of Avian flu’. (7) The fact there was no evidence of human-to-human transmission with the particular flu virus, was not considered a problem worthy of his attention or their discussion. It served as a convenient cover.

A cover, in intelligence jargon, is defined as concealing the true nature of acts, and the specific concealment of ‘any US involvement’. (8)

The cabinet papers also note the Abbott briefing had taken place a month after Foreign Minister Alexander Downer, however, had ‘advised cabinet on our contribution to international responses’. (9) Finer detail was not clarified.

What has emerged is that the US were indeed mindful of the possible problems emerging with Iraq’s biological and germ warfare arsenal and were quietly preparing their allies to take the necessary precautions. (10) They were aware of the implications arising from the civil war in Iraq and the arsenal falling into the wrong hands.

The cabinet of the day played down any unnecessary publicity although ‘the strengthening of surveillance systems’ and intelligence assessments of wider society formed part of the provision, with further planning scheduled to take place the following year. (11)

Contact tracing facilities, to monitor wide sections of Australian society, were also discussed. (12) The provision was already in place, as declassified documents have revealed. (13)

At no time did the cabinet of the day criticise the US for its disastrous invasion plan of Iraq, or accept any responsibility, whatsoever, for participating in the debacle. Meanwhile, the Australian general public were subject to daily media releases which glossed over the situation inside Iraq. It has continued to the present day.

Such behaviour, by those based in higher-level positions in Canberra, does little to enable the assimilation of people from countries such as Iraq and the surrounding region to settle comfortably in Australia. In fact, it has contributed more toward their marginalisation, with all the related problems which that political position entails:

We need an independent foreign policy!

1. Iraq War, 20 years on,

The Conversation, 17 March 2023.

2. Impetus behind wartime support,

Cabinet Archives, The Australian, 1 January 2026.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. See: The US Army and the Iraq War, (January, 2019),

Volume 1, 2003-2006, ISBN 1-58487-774-X,

with specific reference to: From Insurgency to Civil War, 2004-2006,

Conclusion, Volume 23, pp. 653-59.

6. See: Iraq’s Biological Warfare Program,

The Washington Institute, 6 February 1998, which has provided full details of a

clandestine operation in the 1979-85 period.

7. The pandemic plan Australia had – 15 years before Covid,

Cabinet Papers, The Australian, 1 January 2026.

8. See: Instructions for the co-ordination and control of Navy’s clandestine intelligence

collection program, Washington, Top Secret, 7 December 1965,

Declassified: 13 July 1990 / CNO OP-092 CNIC.

9. Pandemic plan, Australian, op.cit., 1 January 2026.

10. See: Plague Wars, T. Mangold and J. Goldberg, (2001).

11. Pandemic plan, Australian, op.cit., 1 January 2026.

12. Ibid.

13. Army’s Project X had wider audience,

The Washington Post, 6 March 1997, and,

Lost History: Project X,

The Consortium Magazine, 31 March 1997.