By Binoy Kampmark

In Australia, whistleblowers are feebly protected. They tend to muddy the narrative of perfect institutions, spoil the fun of having illusions, and give the game away. Despite recent amendments to the Public Interest Disclosure Act 2013 (Cth) regarding, for instance, the creation of a National Anti-Corruption Commission, public sector employees remain vulnerable to prosecution. The NACC, for one, already risks being hobbled by secrecy restrictions imposed by the Albanese government.

At his October 23 National Club Press address in Canberra, Peter Greste was not optimistic about the chances of true, substantive reform that would protect those civil servants “sitting on something that you know is wrong” and “contemplating going to the media” about it. “You are seeing, on the one hand, the fairly technical changes that have been made so far, the rhetoric coming out of the Attorney-General’s office, which is encouraging on one level.” Yet “you see the kind of suffering that David McBride and Richard Boyle have both experienced: the cost of their careers, the financial damage, the emotional stress, the trauma that they have been through, and the fact that they are both about to be in court and quite likely, wind up in prison.”

McBride and Boyle fit the bill of the whistleblower a bit too well – at least from the institutional perspective. The institution exposed can tolerate change, will permit modest reform, will even allow some dispensation and compassion – except for those who unmask the show in a profound, comprehensive way. Hence their prosecution.

McBride’s unmasking activities were related to the reputationally infallible special military forces of Australia, performing supposedly unblighted roles in broken Afghanistan. The exposure of alleged atrocities destroyed a myth while also placing a sharp spotlight on command responsibility. These men might have behaved abominably, but such abominations had a tracing line back to Canberra.

Attempts by McBride to make use of the PID Act were foiled by interventions made in 2022 by the Commonwealth. This was largely because of arguments made that McBride’s evidence would fall within the scope of a public interest immunity claim, thereby restricting it. Such an immunity is the enemy of the whistleblower, enabling the government to block and limit adducing vital evidence in court. Its blighting rationale is that the public interest is not served by the public knowing what the government is up to, despite the official propaganda that an informed citizenry is exactly what is desirable.

This fact was already yoked by the application of the National Security Information (Criminal and Civil Proceedings) Act. This perplexed Kieran Pender of the Human Rights Law Centre. “The NSI Act was enacted to eliminate the need for public interest immunity claims to be made in such circumstances.”

Boyle’s disclosures related to exposing a particularly aggressive practice the Australian Tax Office adopted in raising extra revenue: the garnisheeing of accounts of supposedly errant taxpayers. Such harsh notices require banks to transfer taxpayer monies without notification. Despite going through the awkward hoops set by the PID Act, which privileges internal, and thereby containable disclosure over external, and more accountable review, Boyle found himself facing prosecution for 66 charges (the number has been whittled down to 24) for what he thought was a protected public disclosure to the media. The charges are based upon alleged breaches of the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) and South Australian laws covering the misuse of listening devices.

When he tested the application of the PID Act in the South Australian District Court, the judicial reception from Judge Liesl Kudelka was icy. Such disclosures were, it was held in March, important but confined in their scope. Had “Parliament intended that a public official may engage in criminal conduct when preparing a public interest disclosure (perhaps on the basis that it is a lesser evil for a greater good), then a legislative provision which clearly delineated the boundaries of the conduct would be expected”. In an interpretation that culls the PID Act of effect, the judge effectively claimed that public disclosures would always exclude the preparatory stages of making them.

In the ancient, archaic traditions of authoritarian power, both men are at the strained mercy of the Attorney-General’s discretion as to whether these prosecutions continue. But Mark Dreyfus, the current occupant of Australia’s highest law office, has shown no interest in dropping them, despite having the authority to do so under Section 71 of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). As former senator Rex Patrick has pointed out with his usual sting, claims by Dreyfus that he can only do so in “exceptional circumstances” is bilge watery nonsense. The discretion, as confirmed by the full bench of the Federal Court in 1984, is ‘unfettered’.

Greste’s address was hardly of the window-breaking, stone throwing variety. Having already been blooded in terms of his incarceration for his work with Al Jazeera (he did have a spell in an Egyptian prison for 400 days), he has become, essentially, an establishment voice within the Fourth Estate, an aristo keen on reform as he brandishes a champagne glass in one hand, and a sample of canapes in the other.

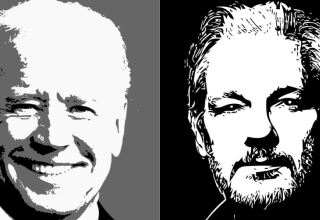

It perhaps explains why he has had reservations about those alternative mischief makers such as Julian Assange, who undeniably engage in journalistic practices (publishing leaks and secrets, much of it the bounty of whistleblowing), but who never quite find their mark as worthy of the same protections.

It would explain Greste’s 2019 opinion piece, written in the aftermath of Assange’s eviction from the Ecuadorian embassy. Filled with inaccuracies and cloddish understanding, he was emphatic: “To be clear, Julian Assange is not a journalist, and WikiLeaks is not a news organisation.” Press freedom, he claimed with strained novelty, was separate from “the libertarian ideal of radical transparency”.

Such tormented reasoning – and one happily embraced by Assange’s US prosecutors – has since come back to haunt Greste. As leader of the Alliance for Journalists’ Freedom, he finds himself campaigning for press freedom alongside bodies such as the Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance who have argued that the prosecution of Assange is “the most dangerous threat to press freedom today”.

Be that as it may, Greste advocates a standalone Media Freedom Act along with firmer protections for whistleblowers. Doing so would certainly get around the troubles journalists face when confronting search warrants of the sort used by the Australian Federal Police against the ABC in June 2019. But constipation obstinately reigns in this field of policy, and more needs to be done.

As a number of independent MPs have recommended (Helen Haines and Andrew Wilkie come to mind), an independent office specifically dedicated to protecting, advising and shielding whistleblowers would go some way in this endeavour. The Netherlands furnishes us a solid, though imperfect example of such a body in the Dutch Whistleblower Authority Act. Adding to this such provisions as the EU whistleblowing directive, and reform in Australia can take place along well-guided lines. That, however, promises to be some way off. Jealously guarded secrecy, however rational, remains the prerogative of the Commonwealth.