by Humphrey McQueen

Have you paid much attention to your Xmas card stamps? In this article, McQueen surveys Australia’s stamp history. Commenting on the contenders who got a guernsey, he points out that First peoples’ art is missing, other than for mere decoration, from the collection. Given the current state of vitriol and ideological state of affairs in Australia First Peoples’ art won’t appear too soon on Aussie stamps. The conqueror’s mentality prevails.

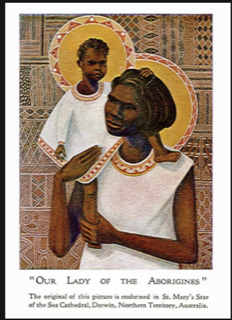

When Pope Paul VI visited Australia in December 1970, the Vatican issued commemorative stamps. One is of St Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney. The other shows a painting from the St Mary’s Star of the Sea Cathedral in Darwin entitled ‘Our Lady of the Aborigines.’

When Pope Paul VI visited Australia in December 1970, the Vatican issued commemorative stamps. One is of St Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney. The other shows a painting from the St Mary’s Star of the Sea Cathedral in Darwin entitled ‘Our Lady of the Aborigines.’

The artist was a Czech, Karel Kupka, who lived and worked with Aborigines in northern Australia, on and off, from the mid-1950s. Darwin’s Bishop O’Loughlin commissioned him ‘to bring religion to the people in terms of local understanding’ by creating something similar to Chinese and Japanese Madonnas.

The Virgin’s face is individual and the child is a person, each expressive of ‘nobility and natural dignity,’ in the words of the Darwin missionary, Father Frank Flynn.

Our eyes are drawn to the arrangement of the figures, like a Byzantine icon, and the flatness in indigenous imagery. The backdrop and the haloes are cross-hatched. Instead of being cradled, the Christ child is perched on his mother’s shoulder, in the manner of Tiwi Islanders.

Colour reproductions sold throughout the world.

In 1962, a columnist with the Melbourne Herald noted that a 16th-century sculpture of Madonna and Child was to be on that year’s Christmas stamp. In praising ‘Our Lady of the Aborigines’ as ’a real Australian Madonna and Child,’ he asked, ‘How about it for next’ year’s Christmas stamp?’

Indigenous designs on stamps began from 1930 as a framing device. Scores have depicted arts and crafts although no named individual appeared until Albert Namatjira in 1968. Two warriors threaten Cook in 1970.

Over sixty-four years, Australia has never issued a Christmas stamp with an Aboriginal artwork let alone a Black Virgin and Christ child.

To ponder why not is to weave through religion, politics and commerce.

While Kupka was painting ‘Our Lady of the Aborigines’ in 1957, the Post-Master General worried about what to put on the first Christmas stamp. The government had endorsed the effort to ‘Put Christ back into Christmas,’ a counter to the ‘X’mas of the market.

The campaign was one element in a decade of revivalism. Two months after the defeat of the referendum to ban the Communist Party in September 1951, Church leaders and the Chief Justices of every State signed ‘The Call’ to FEAR GOD, HONOR THE KING to conquer moral apathy. In 1953, Father Peyton brought ‘The Family That Prayers Together, Stays Together’ from the U.S. of A.; Sydney’s Rev. Allan Walker initiated the biennial National Christian Youth convention in January 1955. Proselytizing culminated with the Billy Graham Crusade during 1959.

In those days, acceptance of Christianity as the national faith was as wide as its sectarianism ran deep. Some Protestants feared the Scarlet Woman of Rome as much as the Red Menace from Moscow. Anti-Papism was complicated by those Protestants who looked upon any religious image as idolatrous. How a put Christ back into Christmas while ignoring his mother?.

Postal officials hoped that they had a solution by adapting a child at prayer from Joshua Reynolds. Since then, most have been of European high art with only a couple by local settler painters, including an Old Master from a Melbourne art student for 1970.

While the threat on the world stage was Atheistic Communism, the challenge at home came from capitalism as affluence and advertising gained ground with Rock-‘n-Roll, television, poker-machines and moves by trading banks into Hire Purchase. In 1957, fifty manufacturers, wholesalers and retailers set up the Father’s Day Council to peddle aftershave and cufflinks.

Stamps also became merchandise; new issues went from four in 1957 to forty by 1991.

Suitable subjects on stamps shifted from the Windsors and local fauna to the Country Women and Young Farmers before honouring the Sydney Stock Exchange in 1971 in the backwash of the Poseidon scandals.

Given the original intent, the Santa on a surfboard for 1977 brought outrage but during the 2000s, the standard became two Christian and four commercial.

The Catholic-Protestant divide has been displaced by fracture lines through multi-cultural society with what the British Army used to call ‘fancy religions.’ The numbers reporting no commitment also shot up.

More than half of those who identify as Aboriginal in the census describe themselves as Christians.

The booming market for indigenous art did nothing to prevent a storm of vitriol pouring over Vincent Namitjira after he took out this year’s Archibald Prize for a portrait of himself with Adam Goodes.

Hence, even with support from a choir of columnists at the Melbourne Herald, gaining permission from Julie Dowling to reproduce her ‘Black Madonna: Omega’ (2004) on next year’s Christmas stamp – fifty-one years after the Vatican issue – might prove ‘courageous.’