CONTENTS

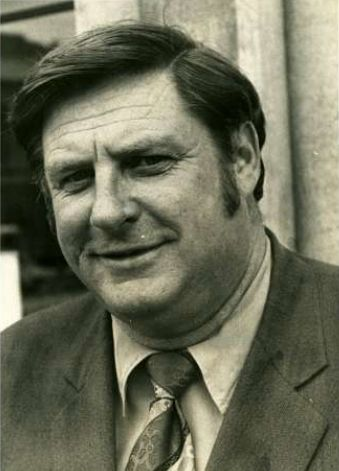

Norm Gallagher, an important leader of the BLF and the Australian Labour Movement

INTRODUCTION – Brian Boyd

REVIEWING THE PAST, RENEWING THE PRESENT – Norm Wallace

RECOLLECTIONS – Paddy Donnelly

NORM GALLAGHER AND THE GREEN BANS – Dave Kerin

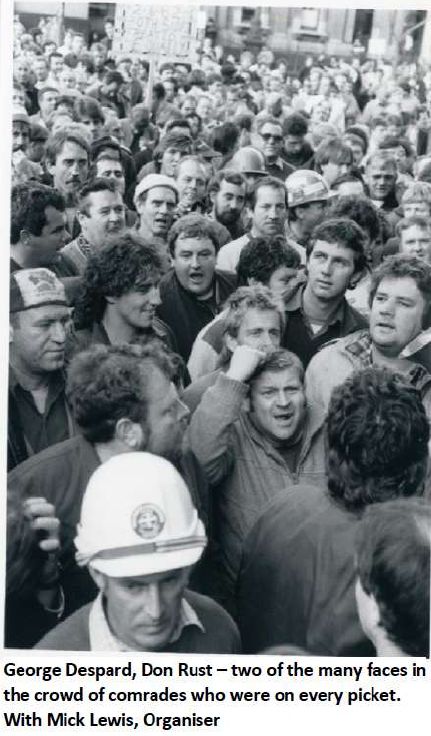

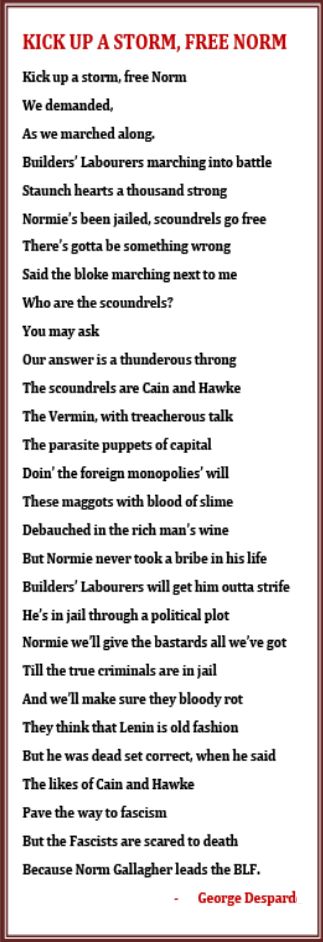

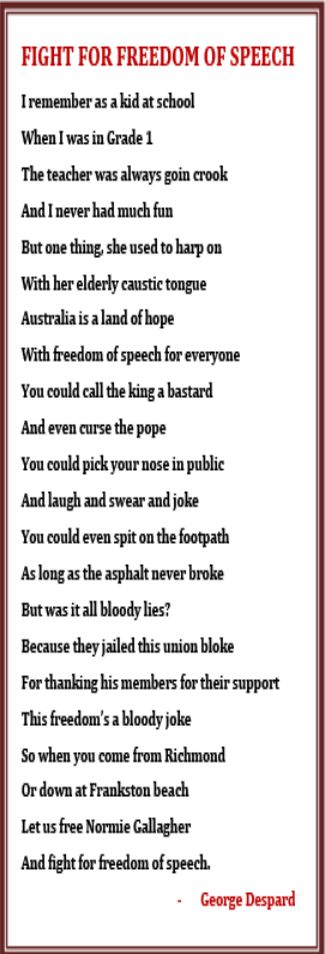

KICK UP A STORM, FREE NORM – George Despard

A special acknowledgement to Malcolm McDonald former Victorian Secretary of the FEDFA, for his recollections and editorial support.

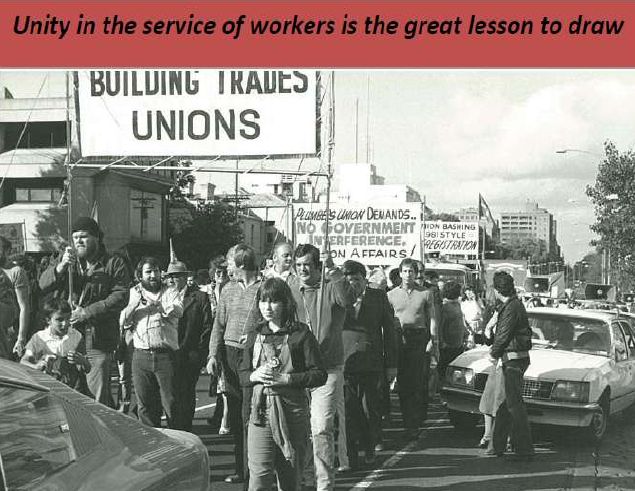

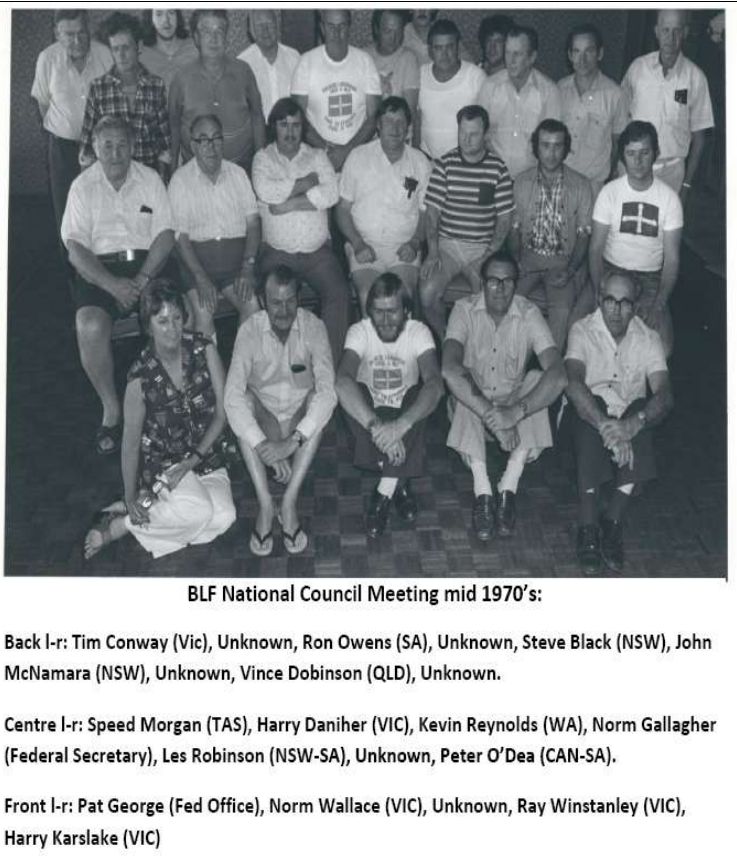

INTRODUCTION WW2 TO 1986

– Brian Boyd

It has been a perennial problem for the union movement to pass on to new generations of workers how their working conditions and wages were achieved. Many an activist unionist has bemoaned how younger workers take for granted the conditions they enjoy, or worse, believe it all comes from the “good heartedness” of the boss.

The industrial and political impact of the BLF, especially between WW2 and the early 1980’s, is a story that should be told as a contribution to informing workers of the 21st century how key established working conditions were won through much struggle, over long campaigns.

The BLF one out, but often in concert with other building unions, deserves due recognition for the establishment of many entitlements which we expect today, and which are outlined by Norm Wallace below.

Many gains initiated in the nation’s building industry would often transfer into other industries. The history of the struggles of the BLF, are rich in lessons for today’s union movement. As we go forward

into the second decade of the 21st Century, we see unions under pressure as always by the ‘powers that be’.

The BLF under the leadership of Paddy Malone and Norm Gallagher saw the practice of ‘putting politics in command’ as a guiding principle for the union. It was no secret these two BLF leaders were

communists. They responded to the needs of the union’s membership from a working-class point of view.

In turn, they responded to the various issues raised by the wider community with a united front approach, when that was possible. Gallagher would lend a sympathetic ear for example to the

conservation causes of protecting heritage buildings. Around Melbourne BLF ‘Green Bans’ would be crucial in saving from the wreckers ball a number of Melbourne’s icons; these are referred to by Dave Kerin in his piece below on the Green Bans.

Gallagher would argue it was important for the militant BLF to have good relationships with the community. The union’s enemies, he pointed out regularly, would always try to isolate the BLF from the public in order to try to weaken its contributions to both the rank and file and around wider social issues.

All of this suggests there is much worth in recording the narrative surviving from the days of the Builders Labourers federation. The fight to defend workers’ rights remains the key task of Australia’s union movement. A wider appreciation of the story of the BLF can contribute a positive input in this regard.

Such a story is characterised by struggle, by wins and losses, resulting finally in improved wages, working conditions and conservation.

The political and industrial conflicts the BLF had with employers and governments contain many lessons. The BLF saga is a history that has yet to be fully recorded, never mind given some practical analysis.

The role of Norm Gallagher as a senior figure in these four decades of the building industry deserves some wider and deeper considerations as well. The conservative, capitalist media has given a biased, one sided view of the BLF and Gallagher over the years.

When the BLF was deregistered in 1986 and again finally in 1991, with the various States based branches of the union eventually merging in various ways with the CFMEU, the historical contribution of the BLF tended to be overlooked, as the years went by.

The BLF was definitely an industry leader in pushing for proper wage rates and working conditions on the nation’s building sites. Achieving a fair rate for a builders labourer, in comparison to the rates established by the traditional industry tradesmen like carpenters, painters, plumbers, electricians, boilermakers and the like, was a BLF ‘cause celebre’ for years. Norm Gallagher insisted this was a key focus of the union; that is, a builders labourer is not a second class citizen in the industry. When the BLF began covering the crew of the tower cranes, as they became widely used, it determined this class of worker deserved due remuneration. Tower cranes were a big technological advancement for the construction industry as the nation developed and built more diverse infrastructure.

When the BLF began covering the crew of the tower cranes, as they became widely used, it determined this class of worker deserved due remuneration. Tower cranes were a big technological advancement for the construction industry as the nation developed and built more diverse infrastructure.

Scaffolders and riggers were also given ‘special status’. Enhanced wage rates were fought for. Of course steel fixers and concreters were crucial contributors to the construction process. They too deserved their own wage bracket.

The progressive left politics of the BLF demanded that even the basic builders labourer was skilled at the end of the day and his or her rate was respectfully linked to the hierarchy of wages fought for over the years. These were printed in their thousands and distributed on a regular basis to every BLF member, organisers and shop stewards. A BLF wages sheet was often used as a recruiting tool on the smaller, less organised sites, where more often than not it was the builders labourers who were getting ripped off.

Wider collective industry or site agreements for all building workers were regularly instituted by the BLF. Construction work associated with the 1956 Melbourne Olympic Games saw the establishment of the industry’s first Building Industry Agreement (BIA). The concept took off in the proceeding years.

Leaders like Paddy Malone and Norm Gallagher took many social and political issues to the rank and file for their consideration. As communists they encouraged BLF members to take on issues like the injustices inflicted on Aborigines, the US war in Vietnam and the Apartheid system in South Africa.

When conservative governments tried to destroy the original Medibank (now the Medicare system), thousands of builders labourers joined with other unionists and community groups and took to the streets in protest. Yes, the BLF story is worth telling and passing on. However, this is not the end of the bigger story of Australian building workers and their unions.

REVISITING THE PAST, RENEWING THE PRESENT

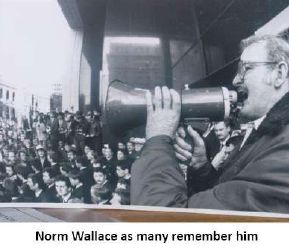

– An interview with Norm Wallace

It is a fact that many Australians are often ignorant of the debt owed by society to trade unions.

Norm Wallace is now 85 years of age and a former official of the Builders Labourers’ Federation (BLF). He regrets the fact that many workers and the general population don’t realize that it has been Australia’s trade unions, that over many years fought for and won so many of the social and working conditions that are now enjoyed but taken for granted , with unions not getting the credit that history should accord them.

One trade union that took a leading part in obtaining and improving the conditions of Australian workers was the Builders Labourer’s Federation. This union for a significant part of its history had a leader named Norm Gallagher.

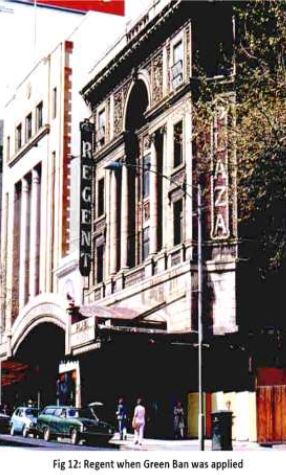

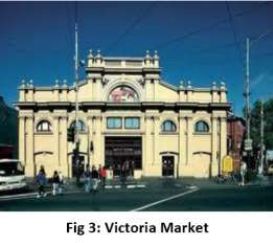

Today not many people realize that during the 1970s, without a trade union called the Builders Labourers’ Federation (BLF) and its leader Norm Gallagher that Melbourne’s much loved Victoria Market would have been demolished by the developers hammer and lost to the people of the city. Gallagher and the BLF after being asked by members of the public for support also stopped the demolition by developers of a number of other Melbourne historical icons such as the Regent theatre, the Melbourne City Baths, Mac’s Hotel and the Windsor Hotel. Gallagher went to gaol for 13 days because he and the BLF campaigned against development on parkland in the Melbourne suburb of Carlton.

The appropriate placement of commemorative plaques on or near places such as the Victoria Market and the Regent Theatre, would record for now and also posterity, how a union of builders labourers placed

work bans on demolition, that saved these assets for the people of Melbourne. For the best part of 20 years up until 1986, the name of Norm Gallagher was known in every Australian house-hold. Newspapers would have photographs and constantly provide stories of his exploits. Gallagher was famous because he was the militant leader of the BLF. Gallagher was born in the Melbourne suburb of Collingwood on 20 September 1931. Leaving school early, his vocabulary and mode of speech was a product of the street as well as a limited education. This boy who started life without privilege or opportunity, achieved much during his time as a unionist. He became an organiser with the BLF in 1951 and becoming Federal Secretary of the union in 1961, he was later elected as Victorian BLF Secretary in 1970.

Wallace was a BLF official in Victoria from 1961 until 1988. He first met Norm Gallagher in 1950 when he and Gallagher were young members of the BLF Victorian Committee of Management and when the highly respected Paddy Malone was Victorian State Secretary of the BLF. Norm Wallace was forced to finish his employment as the BLF Assistant Secretary in 1988 when the union suffered financial problems because of the loss of membership and revenue following the Deregistration of the BLF, and carve up of its members to other unions.

Wallace says that when Norm Gallagher became an organizer with the BLF in 1952 he was part of a team of officials working in a well organized trade union led by the respected and extremely capable Irish and Communist trade unionist Paddy Malone. In addition to being Federal secretary, Norm Gallagher became Victorian State secretary of the BLF following the death of Paddy Malone in 1970. Early in Gallagher’s career as a BLF organizer he had joined the Communist Party

Perhaps apart from members of Norm Gallagher’s family, there would not be anybody who knew and understood the personality of Gallagher and knows of his achievements as thoroughly or deeply as Norm Wallace. He describes the Norm Gallagher he knew as someone who was smart, strong and courageous who could sometimes have an abrasive personality. These attributes saw him become, and helped propel him along the path to becoming a famous leader of a famous trade union.

Wallace regrets that unfortunately, much of which that has been written of Gallagher has largely ignored his many positive achievements and concentrated only on his flaws. This has left an unfair and unbalanced history, not only of Gallagher but also the BLF. Such a one sided treatment of trade union history has left a largely untold or misunderstood story of the often enormous good that the BLF under Gallagher’s leadership was able to achieve not only for BLF members but for other workers as well.

Gallagher after attaining the federal leadership of the BLF in 1961, with Paddy Malone as his mentor grew in confidence and experience. He saw his then main responsibility as improving the Commonwealth arbitration awards covering wages and conditions of builders labourers throughout the Commonwealth. He also supported and encouraged campaigns throughout the country including Victoria where the BLF under the leadership of Paddy Malone was campaigning to improve the wages, conditions of Victorian builders labourers and other construction workers.

Following the leadership and high standards example set by Paddy Malone, Gallagher’s subsequent industrial campaigns continued to disturb the historic nexus between the wage rates of carpenters and other tradesmen in the construction industry. Builders labourers such as scaffolders, riggers, dogmen, concreters and steelfixers had skills that were still undervalued. Some of the biggest gains in Victoria were made by agreements on behalf of scaffolders. Much to the embarrassment of other construction unions including the tradesmen’s unions, Gallagher’s builders labourers’ pay rates eventually became the benchmark for other construction unions to try and gain increases for their members. The increased rates of pay for crane crews operating lofty cranes on building sites achieved by the BLF and Gallagher became the envy of the construction industry.

After becoming BLF Federal secretary, Gallagher never hid his ambition to make the BLF the dominant union in the Construction industry, but also importantly he wanted protective union coverage for BLF work because of the constant demarcation disputes the BLF was having with the FIA and AWU. Against often strong and fearful opposition from other construction unions, and after making promises not to try and take the work covered by other unions, Gallagher in 1972 succeeded in having the name of the BLF changed to the more potentially expansionary and ambitious Australian Building Construction employees and Builders Labourers’ Federation (ABCE&BLF) Despite the name change the union was still usually referred to as the BLF.(1)

Gallagher was still Victorian and Federal Secretary of the BLF when it lost many members to other construction unions following deregistration as a federal union by the Commonwealth government and by state governments in NSW and Victoria in 1986. Gallagher continued to lead a much smaller BLF until 1991. He died eight years later in 1999. The BLF was finally amalgamated into the Construction Forestry Mining and Energy Union in 1994.

Wallace speaks of Gallagher as someone who had the capacity to make his share of enemies but whom despite his often rough manner, could be a friend and inspire intense loyalty amongst officials, friends and members of the union. His door was open to people who came into his office with wide ranging worries that were not always industrial in nature. These could include down of luck members who maybe needed jobs or help with legal problems. He would try and render assistance or direct them to where they may find help.

A sign over Gallagher’s office door read:

“In any dispute between the worker and the employer, the worker is always right”

The BLF like most trade unions provided free legal advice to members concerning workers compensation usually by arrangement with a firm of Labor lawyers such as Holding Redlich or Slater and Gordon. In addition to this service, under Gallagher’s leadership the BLF was one of the few unions that at the time had a paid official who’s only work was dealing with the personal problems of members and their families as well as assisting with workers compensation.

Gallagher had friends amongst the employers as well as other unions and the general community. The developer Bruno Grollo was an employer who genuinely liked and respected Gallagher despite the BLF leader sometimes giving him a hard time. The well known Catholic priest Father John Brosnan who worked at Pentridge Prison in Melbourne was proud to call Norm Gallagher a friend.

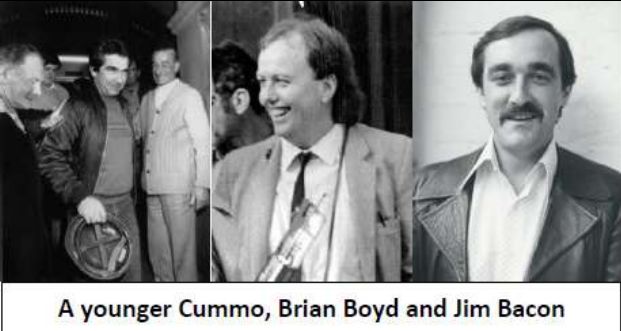

Gallagher knew that he needed a good general staff if the union was to continue being successful. He did not hesitate to employ as organisers for the Vic branch young, militant academics from university who had proven their loyalty to the workers while working as builders labourers. one of them, Jim Bacon from Monash university, was to later become a Labor premier of Tasmania while another Brian Boyd from Latrobe university, became secretary of the Victorian Trades Hall Council. A much admired BLF official who came to the BLF after also studying at Latrobe University was John Cummins.

Seeing the need to keep abreast of technical advances, Gallagher never hesitated to invest in the latest technology for the BLF office and officials. This involved buying an early computer and an early version of a colour printer. Another initiative that also set the tongues of other building unions wagging, was the installation of two way radios in organizers cars, this was long before the invention of mobile phones and was a great advance in communications for the union.

Norm Wallace recognizes and stresses that it was not only the BLF or builders labourers who won conditions for workers in the construction industry. Over the years since the end of the Second World War, the Victorian building unions have acted together as members of the then Victorian Building trades Federation and the Melbourne (now Victorian) Trades Hall Council Building Industry Group. He also fondly remembers the many individual Plumbers, Carpenters, painters, bricklayers and officials of the various unions who along with builders labourers fought in now forgotten campaigns that yielded the conditions enjoyed by construction workers today.

SUPERANNUATION

In giving due recognition to other unions, Wallace also believes that the often leading and vigorous role of BLF officials that helped win conditions for construction workers should be recognized and appreciated. In particular he refers to the campaign for the winning of superannuation in the construction industry in 1984. This was arguably the most far reaching and important of the BLF and Norm Gallagher’s many industrial achievements. This was because of the flow on effect to other industries where campaigns for superannuation were also in progress. History records that the first union superannuation and industry scheme for members was started by the Storemen and Packers union in 1978. Historically the BLF and the construction industry was not the only union or industry, that fought successfully for the establishment of superannuation. It can however be strongly argued, that the BLF under the leadership of Norm Gallagher played an indispensible role in eventually establishing superannuation for all Australian workers.

It is true that Gallagher originally had doubts about the principle and application of superannuation in the construction industry, but once he and his union made the decision to support it, the BLF with encouragement and a request for help from the ACTU, provided the industrial foot soldiers and most of the muscle and strength amongst building unions

that established superannuation for all building workers.

The ACTU and other unions were able to use the example set particularly by the BLF in the building trades throughout Australia, to help unions and workers campaigning for superannuation in other industries. Eventually by act of parliament in 1992 the then federal Keating Labor government, legislated for all Australian workers to have the equivalent of 3% of wages as superannuation paid for by employer contributions, the payment is now 9%.

SITE ALLOWANCES

The BLF and construction unions building unions have had a long history over many years of disputes in fighting for extra pay through site allowances. Site allowances were established and based on such things as disabilities suffered by workers, the cost of the projects, the possible geographic isolation of sites and the type of construction such as the Shopping Centre agreement. Frequently site allowances were negotiated by the unions with individual developers and contractors against strong opposition from the Victorian Master Builders Association. Construction workers of today benefit from site allowance payments established by unions and unionists in the past, and which are now paid as part of the Victorian Building agreement.

FARES AND TRAVEL

In 1938 fares were six pence per day if working outside a 12 mile radius of the GPO. If working within the 12 mile radius, the first threepence for fares was paid by the employee. (1)

It would have often been a problem for builders labourers and other construction workers to use public transport whilst travelling to and from work. In the case of builders labourers, they needed to carry and supply their own picks, shovels and hods, when starting and finishing jobs. The only concession from the employer was that builders labourers could sharpen their picks on the job. One can only imagine the nightmare of trying to carry picks, shovels and hods onto sometimes crowded trams, buses, and trains, very few people had cars during this period. Bicycles would have often been used to transport tools. The practice of builders labourers needing to supply their own tools was ended in 1945. (2)

The BLF and other construction unions have waged a never ending campaign since the 1940s, to gradually improve fares and travel allowances paid to construction workers. Up until the election of the Hawke and then the Howard governments, allowances for fares and travel were not taxed. The unions campaigned successfully for the amount of tax to be reimbursed by the employers. Construction workers are one of the few groups of workers who have allowances for fares and travel to work.

MEDIBANK

In 1976 the newly elected Fraser government commenced to dismantle the benefits of Medibank the universal health care system that had been introduced by the Whitlam government in 1975. The BLF and other construction unions stopped work along with all ACTU affiliated unions to defend Medibank. (1)Despite the union campaign, the Fraser government was able to dilute some of the benefits of Medibank. The unions continued campaign to restore the benefits of Medibank was successful when the Hawke Labor Government was elected in 1983 and restored the benefits of Medibank under the revised name of Medicare. The union campaign to save and restore a universal health care system for all Australians is another example of the benefits received by society generally as a result of trade unions.

INCLEMENT WEATHER

Most construction workers for the first time had an award provision that provided an entitlement of eight hours per month payment for inclement weather in 1945 (1). In 1963 against union opposition, the employers successfully applied to the Arbitration Court to have the entitlement changed from inclement to rain only (2). This meant no lost time payment if workers stopped work because of heat, high winds, severe dust or cold. Led by the BLF and the other construction unions, many disputes erupted on jobs over time lost for other than rain. In a landmark dispute Wallace recalls workers employed by Lewis Construction stopping work when the temperature had reached 108 degrees Fahrenheit (42 degrees Celsius). After Lewis construction refused to pay for the time lost the workers stopped work for two days. Lewis Construction was forced to agree to pay for the day lost and to pay future claims for time lost because of heat. The builders labourers, carpenters and other workers didn’t demand payment for the days they were on strike from Lewis Construction, declaring that they had gone on strike for a principle and they had won. It took until 1966 and after many disputes for the unions and workers to be successful in restoring the pre 1963 broader inclement weather entitlement in the award. (3)

AMENITIES

In 1945 the employer did not need to provide change sheds unless there were more than 15 workers on site (1). By 1959 the employer was forced by the award to supply change sheds if more than 10 workers were employed. (2)

Norm Wallace stresses the often leading role of BLF officials in organizing improved amenities following the end of the Second World War and during the 1950-1960s when even the best amenities to be found on construction jobs though perhaps satisfactory, would not come close to the quality of amenities later won by unions and which became award entitlements and also provisions of the Victorian Building Industry Agreement (3). In Victoria during the 1950s, the Mobil refinery in Altona, the APM in Fairfield, and the Housing Commission of Victoria, were examples of larger work sites that had a strong union presence where the workers were able to get agreement to provide decent amenities. By the 1960s, amenities for workers had generally improved and examples of this were the new Melbourne high rise buildings such as Nauru House, Collins Place and the BHP building.

Many times on smaller and isolated sites, amenities could be almost non-existent unless the unions forced them to be provided. Proper toilets were not always available though they were a legal obligation to be supplied by the employer. Usually no toilet paper was supplied, some bosses arguing that “if toilet paper was supplied that the workers would probably pinch it”. Norm Wallace remembers how an over flowing toilet that had belonged to a demolished house, was being used as the site convenience for a block of flats. After the boss and the workers refused to do anything about it, Norm Wallace was forced to bring in the local health inspector who closed down the job until the toilet was unblocked. Often meals and smokos’ were taken in the open despite an award provision that stipulated that a shed needed to be provided. Unions often had to argue that the employer should not use a crib shed for the storage of building materials such as cement. A 1960s campaign was that mess sheds should be separate from change sheds. It was often a battle to have a “Billy Boy” now called a Peggy to make sure that there was hot water for smoko’s and that toilets were cleaned.

DELAYED WORKERS COMPENSATION PAYMENTS

A big worry to construction and other workers was that it was possible for an injured or ill worker to wait at home without pay for maybe months at a time before his workers compensation payments arrived. It sometimes happened that workers had returned to work before they were paid their compo entitlements. To overcome this problem, a demand was placed on the building employers to pay the wages on the next pay day after it was agreed or obvious that a worker had suffered a work related injury or illness. The campaign involved closing down jobs if the employer failed to make these immediate payments to the worker. The employers were able to recoup their payments from the insurance company later.

COMPENSATION MAKE UP

Compensation make up to full wages had been a long standing claim by unions in many industries .This was caused because the amounts that insurance companies paid to workers on compensation was less than normal wage rates. It was bad enough for a worker to suffer the effects of a workplace injury without also suffering the loss of some of his take home pay as well. An industry wide campaign was successful in 1974 in getting agreement that when a worker went on compensation he would not suffer any loss of wages as a result for an up to six months period. This period of make up has since been extended to two years for workers covered by the Victorian Building Industry Agreement.

PAID SICK LEAVE

Important conditions won by the BLF and other construction unions included conditions such as paid sick leave, introduced in 1975. Prior to the winning of this important condition construction workers had a loading in their hourly rate for sick leave. This was OK if workers were not sick, but when they were, they never received any pay for the time that they had off. When the unions won paid sick leave they also continued to receive the sick leave loading. (1)

PORTABILITY OF SICK LEAVE

The first negotiated agreement for portability of sick leave was in an agreement the BLF obtained with scaffolding companies in 1970, while portability of sick leave was not achieved for all construction workers until 1996. Workers sick leave is financed by contributions from the employers and is now accumulated, controlled, and dispensed by the redundancy fund Incolink. (1)

PAID PUBLIC HOLIDAYS

As with sick leave, payment for public holidays was included in the weekly wage as a loading while public holidays were observed without payment. Half payment for observed public holidays was won in 1971 (1), full payment was achieved in 1972.(2).The winning of paid public holidays also saw the retention of the public holiday loading in the wage rate.

PORTABILITY OF LONG SERVICE LEAVE

Portability of long service leave was won by the construction unions in 1976 after a vigorous campaign over many years .Prior to this very few construction workers enjoyed long service leave because they very rarely could accumulate sufficient time with the one employer. Now employers contribute to a central fund that pays for an employee’s long service as it accumulates in the industry, not just with one employer. 1)

SUPPLY OF CLOTHING AND FOOTWEAR

In the early 1970s, BLF members constructing the west side of Melbourne’s West Gate bridge and FIA members working on the east side, were the first workers in Australia to win Bluey jackets on construction as part of an industrial agreement. Tommy Watson, now a CFMEU official recalls another claim was for the supply of safety boots. Following strike action, the bridge contractor and The Metal Trades Industry Association offered to pay for one boot if the workers were prepared to pay for the other one. Jimmy O’Neil a then well known Metal workers union official, told a meeting that “the offer would be a total victory if there were any one legged workers on the bridge”. Amongst the earliest successes in campaigns for supply of clothing and footwear was getting employers to supply rubber boots and gloves (1), steel capped safety boots came later (2).

SEVERENCE PAY

A campaign by Victorian building construction workers to receive severance pay was won and introduced in Victoria in 1987. In 1989 the Victorian unions and employers formed Incolink to administer and invest the accumulated severance funds for the benefit of construction workers. (1) The Incolink fund now provides payments during periods of unemployment and if accrued, upon retirement. Some other Incolink entitlements are free Accident Insurance and ambulance. The fund also provides grants to the construction industry for health and safety projects and assists the running of the Building Industry Disputes Board. The original employer payment for severance in Victoria to construction workers was $20 per week. In July 2011 the severance payment had grown to $66.40. Following the Victorian example, severance schemes also exist for construction workers in other states. (1)

HEALTH AND SAFETY

Every worker on construction knows that no issue is more important than having a safe workplace in what is generally a very dangerous industry. The many years that Wallace spent as a worker and an official with the BLF, saw a lot of his time being spent on checking sites and regularly arguing with employers over health and safety. His recollections of those years as a worker and union official are littered with memories of accidents where workers were killed and sometimes badly injured. As is still the case, bad backs were common and the naturally hard work of builders labourers often led to wear and tear and forced early retirement from the industry. Builders labourers and other workers suffered illnesses caused by the often misguided use of chemicals such as lead in paint the criminal use of products containing asbestos. The worst industrial accident in his experience was in November 1970 when the West Gate Bridge collapsed killing 35 workers and injuring others. Another bad accident in Melbourne that caused the deaths of three workers was when a lofty crane collapsed in 1961 during construction of the Colonial Mutual building in Collins street Melbourne. (1) Importantly, the BLF appointed the union movement’s first National Asbestos Safety Officer in 1982, Brian Boyd.

MAN HOISTS

Agitation by construction unions for the installation of man hoists on health and safety grounds led to many disputes. Before the practice of carrying Hods was banned, builders labourers carrying a Hod of bricks on their shoulders were one group always at great risk of injury, because of the lack of man and materials hoists. A Hod carrying labourer was expected to climb ladders while carrying 12 bricks perhaps weighing 48 kilos up to 15 feet (4.65 metres) and 10 bricks weighing up to 40 kilos to any height above 15 feet (1). Employers often saw the need for materials hoists before man hoists, mainly because of cost considerations. Prior to the introduction of scaffolding stairs in the 1970s, sites without man hoists had access by ladders only. In the late 1960s, unions reached agreement that man hoists would be supplied on buildings of five or more floors. This could still have problems if the building was steel framed and could only be plumbed when the building frame was well advanced. Norm Wallace recalls a 14 floor steel framed building during the 1960s that only had ladder access for workers. Carpenters for example while climbing ladders, had to carry tool boxes to where they were working, this they did with great difficulty risk and physical effort. To improve safety, constant arguments occurred about the type of ladders to be used while demands were consistently made, for the installation of man hoists. While man hoists are now widely used, arguments with employers to install man hoists can still be an ongoing problem.

HARD HATS

Hard hats were first used and supplied on Victorian construction in the 1950s, during construction of the Mobil oil refinery In Altona. They were in general use on Victorian construction sites by the end of the 1960s. Hard hats have been one of the most important improvements to health and safety in the construction industry, but time was needed to convince and educate many workers that it was in their best interests to wear them.

JOB HEALTH AND SAFETY REPRESENTATIVES

Though some employers employed health and safety officers, the BLF and other unions have always demanded that delegates and job safety committees that existed on the larger jobs, should have the final say and main responsibility to look after health and safety. Other bodies concerned with health and safety on construction but which were not proactive in policing sites, were the Victorian State Government Lifts and Cranes Department, while local Councils had responsibility for providing scaffolding and building inspectors as well as health inspectors.

LEGISLATION

Under the influence of the unions, the Victorian Labor government in 1985 passed new and more comprehensive legislation dealing with workplace health and safety. The legislation included the formation of the Government Health and Safety inspectorate Workcover now known as Worksafe. (1) Parts of the legislation were met with fierce opposition from the employers, particularly the section that allowed health and safety reps to be selected from among the workers on individual jobs. The improved legislation covering safety in the workplace also impacted on important matters such as the handling of asbestos, protection while working at heights, limitations on weights that could be lifted or handled, traffic management, working under or near power lines, the safe operation and maintenance of cranes and mechanical equipment. Unfortunately as everybody knows, the existence of legislation and consistent vigilance, doesn’t always guarantee a safe workplace. Therefore the construction unions still need to spend time and effort on health and safety. This includes the CFMEU’S formation of a modern training unit that runs instruction classes on workplace health and safety as well as skill development for Victorian union members. (1 – Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004 (Victoria)

IN CONCLUSION

Norm Wallace has retraced and listed many of the gains won by construction workers since the end of the Second World War. Though now in retirement, he has a continuing interest in trade unions in particular the CFMEU into which the genes of his union the BLF and other construction unions have been passed because of amalgamation. He appreciates that the CFMEU since its formation in 1993, has successfully operated as a trade union that has proven a worthy heir to the traditions of the past.

REFERENCES:

“It is a fact that many Australians are ignorant of the debt owed by society to trade unions”

(1) Commonwealth Arbitration Reports Vol 146 1972 – pp 1052-1054 R – no 200 of 1970 R – no 145 of 1972)

“FARES AND TRAVEL”

(1) Victorian Government Gazette no 355 Dec 2 1938) (2)Victorian Government Gazette no 182 Thursday

Aug 18 1938.) (Victorian Government Gazette no 168 Tues Dec 18 1945)

“MEDIBANK”

(1) Green Left Weekly Wed October 14 1988

“INCLEMENT WEATHER”

(1) Victorian Government Gazette no 168 Tues Dec 18 1945

(2) Dept of Labour & Industry Victoria Determination, Builders Labourers’ Board no 2 1963

(3) Determination Builders Labourers’ Industrial Appeals Court Friday 22 July 1966

“AMENITIES”

(1) Victorian Government Gazette no 168 Tues Dec 18 1945

(2) Commonwealth Arbitration Reports Dec-June 1958-59 Page 183 – Amenities Clause 32

(3) 3-Building Construction Employees and Builders Labourers’ award 1978 Amenities – Clause 34

“DELAYED WORKERS COMPENSATION PAYMENTS”

( 1) Clause 29 BCE@BLA award 1982

“COMPENSATION MAKE UP”

(1) Clause 29 – BCE@BLA award 1982

“PAID SICK LEAVE”

(1) Clause 28 BCE@BLA award 1982

“PORTABILITY OF SICK LEAVE”

(1) Incolink Victoria website

“PAID PUBLIC HOLIDAYS”

(1) – Department of Labour and Industry -Determination of The Builders Labourers Federation no

4 of 1971)(2-Department of Labour and Industry-Determination of the Builders Labourers Board

no 1 of 1972)

“PORTABILITY OF LONG SERVICE LEAVE”

(1) Construction Industry Long Service Leave

Board of Victoria

“SUPPLY OF CLOTHING AND FOOTWEAR”

(1) CAR Dec 1958-59 page 183 Clause 31

(2) (2 – Clause 36 BCE@BLA 1982

“SEVERENCE PAY”

(1) Incolink Victoria website

“HEALTH AND SAFETY”

(1) www.emelbourne.net.au – Industrial

accidents

“MAN HOISTS” (1) Victorian Government

Gazette no 168 Tues Dec 18 1945

“LEGISLATION” (1) Victorian Government

Workplace Health and Safety act 1985– OHS

Act 2004 (Victoria)

RECOLLECTIONS “…NORM GALLAGHER WAS IN THE VANGUARD”

– by Paddy Donnelly

(Paddy was an organizer with the BLF for approximately 10 years between the early ‘70’s and the early 80’s. At left is a photo of him when he started).

This was a time of enormous change across the broad spectrum of the building industry. Campaigns for greater wages and conditions were in full swing, many BLF officials were subjected to the lash of the penal clauses embodied in the award and dragged before the courts, the union was deregistered between 1974 and 1976 but we carried on serving our members with important help from other building unions. In 1980 the BLF became the subject of a bitter Royal Commission that seemed to drag on for ages and where we were found predominantly to be guilty of once again fighting for the rights of the working class. Many will remember that the BLF group required to appear before that inquisition, refused to answer all questions put to them by the court.

The writer had retired from the union prior to the Deregistration of 1986 and therefore deems it inappropriate to comment on this industrial execution. Outlined below are some historical items associated with the early life of the BLF and descriptions of bargaining streams that it was then heavily involved in. This bargaining was steeped in an enthusiasm, vitality and passion by the BLF that foreshadowed to all players across the wide parameters of the industry, that this union had but one agenda – justice for the proletariat and for the ambition for this to see the light of day. While the BLF had been active prior to the end of WW11 it has to be understood that work of the larger variety was not designed to rate highly in the Australian Gross Domestic Product. However from 1944 onward the profile of building unions adopted greater significance with the level of work planned for development and the role of the BLF in this syllabus.

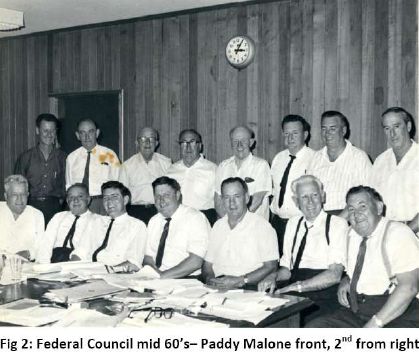

An important event in the union’s history occurred when a small but dedicated group of courageous men gained majority control of the union in 1941. This included the election of Paddy Malone as Victorian State Secretary. Prior to this the union was controlled by men some of whom were of alleged ill repute. BLF elections for committees and other positions ( if required) allowed for a postal vote of members and a ballot of members at the AGM.

The ballot of 1944, saw a further high degree of quality personnel elected to power in the Victorian BLF. The successful 1944 team included the following – (President – J Christie) ( (VP – J Russell) (Secretary – P Malone) ( Treasurer – J Fahey) (Guardian – L Bowden) (Branch Delegates – R Leach – H Mc Shane – J Powell – L Shrendrick) ( Organisers – J Mc Ewan – F Murphy – J Powell) (1) Other important BLF stalwarts helped develop the union from the mid 1940s onwards. These included the legendary, Harry Danagher, who for many years was the Victorian BLF President also J Muirhead, L Prosser, JP Smith, C Heitch, S Drinkwater, J Sharpe, A Way, T Manton, J Toy, E Hanley & N Wallace stood fast in the vanguard.

A DIFFICULT BEGINNING

When the new Secretary Paddy Malone and his team took office in 1941, the books revealed that the Victorian Branch of the Builders Labourers Federation had 1/8 pence (One shilling and eightpence) in the bank. In other words the union was totally broke. However under Paddy’s leadership, and through the efforts of organizers such as the tenacious Scot, Jock McEwan, the BLF, in the fullness of time, became a viable, solvent and respected trade union through the efforts of the above dedicated and militant officials. Within the space of a couple of years (1944 – 1946), the BLF Victorian Branch, was operating on a platform of honesty, integrity, diligence and dedication to the general membership This had an inspirational effect on branches in other states.

PADDY MALONE

Paddy Malone was born & bred in County Tyrone, Ireland. He migrated to Australia in 1927. After spending time in Melbourne, the future BLF Victorian Secretary left to seek his fortune in Queensland. After a seven year spell he returned to Melbourne in 1934 and found work as a builder’s labourer. It was during this period that he became active in a BLF reform group and in the union’s 1939 elections he was elected to the Victorian Executive. In 1941 Paddy, as stated above, was elected to the position of Victorian State Secretary. (2) It is important to realize, that without the BLF changing direction in 1941 under the leadership of Paddy, that its later greatness and success would not have been possible. Paddy Malone has an important historical place in the history of the BLF. This highly respected Irishman who died in 1970 is arguably the greatest ever BLF leader.

NEW BLF LEADERSHIP

Following the passing of Paddy Malone, there were two men of exceptional ability among the officials who went on to lead the BLF in becoming the pacesetter for wages and conditions in the Victorian Construction industry. These men were Norm Gallagher and the indispensible Norm Wallace. Gallagher became BLF Victorian State Secretary in 1970 and Wallace retained the assistant secretary post that he held under Paddy Malone. Under the mentorship of Paddy, Norm Gallagher had also been a successful BLF Federal Secretary since 1961.

CAMPAIGNS

Norm Gallagher upon assuming the leadership of the Victorian Branch of the BLF soon placed himself into a position of power and influence that severely concerned the Master Builders’ Association of Victoria (MBAV). Together with a sizeable band of energetic organizers and a host of zealous job delegates, he increased the intensity of campaigns for “no ticket – no start, (i.e. total unionization of builders labourers) over award payments, upgrading of amenities and other conditions. He also fought for the hiring of older builders labourers as onsite “billy boys” or “peggies” and had great success in getting better pay and recognition for the under-valued skills of a host of long suffering builders labourers.

INTERSTATE SUPPORT

The Victorian Branch of the BLF supported, and had the support of men such as William Leslie “Speed” Morgan, Secretary of the Tasmanian Branch of the BLF whose fearlessness, loyalty and ability to organize was always available in Victoria when the going got tough. In this respect Ronnie Owens (South Australia) and Kevin Reynolds (Western Australia) must also be mentioned.

AN HONOUR TO HAVE KNOWN THEM

Among the many fine BLF organisers who the writer had the privilege of working with, were Norm Gallagher (the General), Norm Wallace, Danny Hellier, Fergus Robinson, Harry Karslake, Jim Bacon (later to become Premier of Tasmania), John Cummins, Martin Greaney, Ray Winstanley, Brian Boyd (later a Secretary of the Victorian Trades Hall Council), Terry O’Connor, Mick Lewis, Jim Fleming, Lex Gribble, Lennie Rourke, Marco Masterson, Mick Papan, Phil Tate, Barry Kent and Norm Rust.3 (Apologies to any names that may have been omitted)

References:

(1) Commonwealth Industrial Registrar

(2) P167-68, “WE BUILT THIS COUNTRY – Builders Labourers’ and their unions” by Humphrey McQueen

(3) “The Hammer and the Heart—-A book of poems and short stories” –By Paddy Donnelly

EXTRACTS FROM PADDY DONNELLY’S MASTER OF BUSINESS THESIS

(COPYRIGHT)

“It is important to note that when work became plentiful post WWII, a dominant feature in wage determination in Australia had been its centralist approach (Arbitration). This was particularity so until 1986 when wages were adjusted according to a range of social and economic criteria expressed through award and over- award payments .Later in this document it will be shown the extent to which the BLF, under the leadership of Norm Gallagher, went to achieve these over- award payments at a time when many others received theirs through flow –on’s from the BLF.

“The emergence of bargaining in the building and construction industry can be traced back to the early 1950’s during a period of strong industry growth. The period between the conclusion of WWII and the early 1950’s witnessed a marked increase in building activity which, in turn, saw full employment and, as stated above, a shortage of skilled labour in the Victorian building industry. Unions took advantage of the economic climate to increase the price of labour and successfully

negotiate a range of improved working conditions such as the provision of tools of trade and protective clothing. The level of union activity in this period culminated in the significant increase in the ‘leap-frogging’* of wages (ie the transmission of elevated wage gains from one company to others).

THE IMPORTANCE OF DEVELOPING KNOWLEDGE OF BARGAINING IN THE EARLY YEARS AND THE FORMS SUCH BARGAINING TOOK.

“Evidence of BLF bargaining can be discerned in the determining of ‘site allowances’ in Victoria from the mid 1950’s onward as they often gave recognition to various circumstances existing on individual sites. These allowances grew out of a range of specific ‘special rates’ contained in respective building industry awards and were designed to compensate workers required to complete duties in adverse conditions. Over time it became industry practice for certain of these rates to be combined in what came to be known as ‘site allowances’. To validate an amount which should be paid on particular sites, the Commission had to be assured that disabilities were actually being incurred.

“This activity departed from the traditional forms of bargaining in later years across the building industry in general in that it adopted the rationale that the larger and more sophisticated the project, the greater the site allowance and other benefits should be. It further contrasted markedly with the original criteria that site allowances be determined on the actual level of disabilities being incurred.

“The irregular nature of employment within the industry necessitated the development of informal bargaining practices. Numerous employers with fragmented control over labour and often lacking negotiating skills were confronted by a variety of well organized and increasingly militant left-wing unions led by the BLF, who viewed the employers as the enemy.

“The bargaining power of building unions, particularly the BLF, became evident in the 1950’s. Their preparedness to operate outside the formal system (the Commission) even when it was delivering wage increases through quarterly wage indexation, is found in the negotiation of an agreement with an American firm, Braun Construction, in 1952.

“This agreement was one of the first examples of enterprise based bargaining and was the principal forerunner to the Melbourne Building Industry Agreement of 1956 (later the VBIA). The Braun Company, anxious to avoid disputes and delays, granted over award wages on a major central business district project, provided that unions agreed to the establishment of a formal disputes settlement procedure. This set the pattern for private agreements to be subsequently struck at company level in the period 1953 to 1956 between the Victorian Building unions and various companies. These groups included Hanstrup Builders, Hansen and Yuncken, John Holland and E A Watts.

“The MBIA commenced on the 23rd August 1956 and was confined to all building and construction works carried on in the Metropolitan areas of Melbourne as defined by the ‘Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works Planning Scheme’ as it was negotiated outside the formal system it had no effect on award conditions as stipulated by the Commission.

“During the period 1956 to 1973 Victorian Building Industry parties engaged in two principle bargaining streams: a) informal through the MBIA and b) within the formal arbitration system. The spreading of the CBD standards across the industry was completed, in many instances, without arbitration. Matters such as work value cases, consent agreements, site agreements and ‘flow-on’ from gains made in other industries were, however, referred to the Commission for arbitration.

“The main characteristics of the MBIA were that it was a centralized agreement negotiated at industry level; there was third party intervention; it subscribed to the notion of comparative wage justice; it was for a fixed term being negotiated on a twelve to eighteen months basis; it operated alongside the formal system (The Commission) while continuing to provide an avenue for over-award bargaining outside the system and it had common operational features to all signatory parties.

The agreement was underpinned by the signatory parties agreeing to subscribe to a range of industry procedures designed to minimise the level of strikes and an inter- party conciliation board which provided a forum for the settlement of disputes.

“The foregoing wage determination processes provide evidence of a hybrid system of centralisation and collective bargaining operating within the Victorian building industry. Whilst certain bargaining outcomes were able to be established informally at enterprise and industrial level, others required arbitration. The fundamental tenets of enterprise bargaining, which seek to enable a firm to obtain and reward competitive gains achieved through more flexible work practices, did not apply in Victorian building industry level negotiations during the period 1956 to 1973. Rather, negotiations were designed solely to stabilise the industry through agreed disputes settlement procedures and to provide equitable gains to all workers.

“However, this type of bargaining, organised within a collective bargaining framework, was relatively short lived due to the brief nature of many building industry projects. Further, the resources required to pursue equity on a company by company basis, tested union resources given the level of employers and projects under construction”.

A BRIEF COMMENTARY ON BARGAINING AND WHY IT HAS BEEN ELABORATED ON.

Bargaining/Negotiating is the pulse beat of industrial relations. Without a workable knowledge of these disciplines, by industry operatives, it could well be argued that the wage-setting, health and safety and the establishment of a host of other working conditions would be jeopardized or even non-existent The BLF found over the years that it was necessary to be familiar with the practice of all forms of bargaining if their members were to be appropriately served and if this meant that “certain toes had to be trod on in the process then so be it”. Further it was not the habit of the BLF to delay carrying out their responsibilities in bargaining processes. They moved quickly and kept the momentum going until the job was done. Norm Gallagher would never have tolerated mediocrity.

It took all of the bargaining processes outlined above to reach the relatively straight forward model(s) that now exist in the building industry. Items that are now taken for granted (eg site allowances, height money etc) all had to be fought for and there was no payment for lost time when workers lost wages in the course of that fighting. It is trusted that the industrial parties of to-day (Good luck to them) appreciate those who paved the way for them years ago and especially that a man named Norm Gallagher was in the vanguard.

A TIME TO LAUGH

The after work drinks at the Dover Hotel two doors away from the Union office were often events to behold, veritable variety shows. Marco Masterson could often be heard singing his favourite song, “Rainbow on the River,” Jim Fleming and Paddy Donnelly singing Irish songs of revolution and When Jim got really passionate he would stand on a bar table with his arm movements akin to those of Pavarotti. Macca Hearst would sweet talk the barmaid; George Despard recited poetry and “Percy” the Publican* thought we were all mad. *(Percy the Publican was Peter Jones, ex Carlton footballer and pub owner)

In earlier days the favoured water- hole was the Lygon Hotel (now the John Curtin) which was owned by “Jack the Hat” Fogarty (not to be confused with another “Jack the Hat” a well known respected waterside worker). When work was over, one of the tricks Paddy Donnelly and Ray Winstanley (Organisers) would get up to, would be to stand on the footpath below Norm Gallagher’s window after work and sing snippets from hymns like “What a Friend We Have in Jesus”, “Let’s All

Gather At The River” and “Drop Kick Me Jesus Through the Goal Posts of Life”. Lex Gribble (Organiser) told Norm that Paddy had started taking Ray to gospel meetings and that they were both off their heads with religion.

Norm told Lex to tell them to piss off as they were an embarrassment to the union and were giving it a bad name. Lex said that would be ill-advised as it would be a breach of the Religious Discrimination Act and he could be sued. Norm said that Paddy was much wiser when he was on the turps and even then he was half mad.

In the end Norm saw the humour in “the footpath serenading” and he and the rest of the boys often had a drink on the strength of it.

A TRIBUTE TO NORM WALLACE

While Norm Gallagher is mentioned in fine detail in this work, and rightly so, no history of the BLF can possibly be afforded credibility without mentioning Norm Wallace, Treasurer/ Assistant Secretary of the Victorian Branch of the Union and a Federal Official also.

The role that Norm played in his time cannot be described adequately in this brief passage but a person of his humility would not be aggrieved by this. Norm had a brilliant mind, was a first rate orator and embraced a dedication to the Union and the working class sufficient for those of us who know him to continue to applaud and hold in high esteem his integrity to the present time. Norm Wallace had a gift of foresight and organizing that few possess. His discipline in the execution of his duties was exemplary; he enjoyed the respect of all with whom he dealt, across the broad spectrum of the Building Industry and beyond.

Where and when the deeds of great Union Officials is spoken Norm Wallace will rate a fond and proud mention. But there was more to Norm than his Union activities, something that may not be as well known as it should. During WW11 Norm was a member of the elite and extremely highly trained Z Special Unit In the Australian Army.

Just to mention one of his and his comrades’ historic deeds the following is cited. In 1945 with the war in the Pacific coming to an end, they parachuted into Borneo and liberated the last of the Australian troops, who had managed to survive the infamous Sandacan-Ranau Death March.

This type of courage and steadfastness continue to be characteristics of Norm Wallace’s life. Norm retired from the BLF in the late 1980s.

“Where and when the deeds of great union

officials is spoken, Norm Wallace will rate a

fond and proud mention.“

THE BLF PICKETERS – A BREED APART

While history records BLF members as having won a multitude of class struggles within the confines of workplaces, another group of stalwarts assisted it markedly by winning a host of union related issues outside forbidding site parameters. These were the picketers who, in tandem with other militants, are deserving of attracting undaunted exaltation. Building industry operatives and indeed many other sectors of society would agree that those who put their bodies on the line, (to use the vernacular), on pickets, played a major role in the propagation of the BLF.

Ever since post WW11 the BLF can be discerned as possessing the dual and unique tenets of determination and ability to operate the picket system where and when required. The pickets, in return, came to understand quickly and robustly that the forward thrust of the union would be constrained if they did not play a spirited role.

It would be a gross fabrication to state that the BLF was one of only a few unions to have used picketing on a regular basis to defend their rights. Indeed many unions which were categorized as being ineffectual, in the volatile sense, used pickets to a greater or lesser degree over a span of years.

The BLF, however, particularly since post WW11, were confronted with class and economic struggles that few unions encountered. For example their militancy in various campaigns on the path towards equity, dignity and overall industrial recognition brought with it many public overtures that communism was rampant within the union, that the union was a breeding ground for communists. This was screamed from the enclaves of the groupers and the pulpits of many churches. The forces of the Federated Ironworkers Association (FIA), the Australian Workers Union (AWU) and certain other unions sought to usurp its constitutional coverage over certain work classifications. In many cases the foregoing groups joined forces with the ruling class and employer groups to curb, if not indeed prohibit, BLF activities.

One would therefore not have to possess a fertile imagination to realize that the BLF required tactical activities both within and without worksites to protect their hard won gains and further such gains in the interests of its members. Hence the enthusiastic use of pickets.

These groups, often as small as two or three persons and on occasions a single person did what they could to prevent scabs entering sites and also deliveries of materials in times of volatile industrial disputes with management. Picketers were often involved in addressing unfair dismissals, health and safety issues and in situations where trade boundaries were manipulated to give others access to BLF work.

I will refrain from singling out any group or individual in this following discourse lest this be at the cost of offending the families of many of those picketers who are no longer with us. I fully understand that families wish to let their loved ones rest in peace.

The neo-classical BLF picketer was an out of work person (but not always) who received no payment from the union or elsewhere for their efforts. Often, on prolonged disputes, they went without many of life’s basic fare. In many cases food stuffs were in short supply and payment of rent and other household needs were a burning issue. These and other vexations affected picketer’s families in adverse situations. I recall being present at a book launch when a cherished stalwart of the union, Mrs. Margaret Kane, said “its incredible the amount of meals you can make with cans of beans when times are bad”

BLF picketers often felt the weight of over-zealous police batons as they stoically defended their stations on site entrances. Others were thrown into paddy wagons and taken to police lock-ups where they were liable to get another beating. Sure, this happened to other union picketers but never with the force, regularity and brutality that it happened to the BLF. The BLF picketers were also targeted by governments, employers and other dregs of humanity for extra special attention. These were not occasional incidents indeed they were repeated over and over.

In all battles the bravest and most resourceful troops are always found in the vanguard. So it was with the BLF picketers, many of whom gave the best years of their lives to the service of their fellow men in many aspects. Such is the essence of bravery, dedication and often loss of blood that these stalwarts bestowed on the union they loved so well.

References:

- de Vyver, FT (I970) The Melbourne Industry Agreement: “A Re-Examination” Journal Of Industrial Relations, Volume 12(2) PP166-181.

- Donnelly, P (1995) “An Examination Of Enterprise Bargaining In The Victorian Building Industry” (1995) (September 1992– September 1995) Contemporary Bargaini ng In The Victorian Building Industry — Enterprise, Industry Or Pattern Bargaining? Master Of Business Thesis, PP 38–52.

- Plowman, DH “Developments In Australian Wage Determination” (1953-1983) The Institutional Dimension, In Niland, J. (ed)Wage Fixation In Australia. Allen & Unwin, Sydney, PP75-98

- Wallace, N. “Interviews On Post WWII BLF History”–Periodic Sessions, April 2011-August 2011.

NORM GALLAGHER AND THE GREEN BANS

– by Dave Kerin

Norm Gallagher was a supportive leader in the constant and unrelenting battle fought daily by Builders Labourers for their rights.

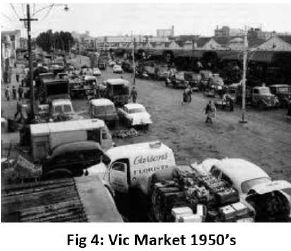

Norm was 14 when he went to work at the Victoria Markets, starting at 3:30 in the morning in the vegie section. A few years later in 1951, he was elected to the union executive of the Builders Labourers’ Federation. In 1961 Norm became General Secretary of the union and also became Victorian Secretary in 1970. He remained its General Secretary until 1992.

During the 1960’s and 1970’s many played similar leadership roles across an intensely contested left political spectrum. From activist rank and filers, shop stewards and delegates through to Jack Mundey, Cummo, Norm Wallace, Ted Bull, George Crawford, Mick Lewis, John (Bluey) Rutherford, John Halfpenny, Malcolm MacDonald, George Zangalis, Marco Masterson and Len Cooper to name just a few. All were socialists by conviction.

Such was the fervour and strength of their conviction that in every case their unionism was inseparable from the struggle for a better world, not only a bigger share of this one. The contradiction at the heart of the work across that left spectrum however, was the ill-founded conviction, held to more by some than others, that there was one correct way to achieve that change and one, correct party of people as the arbiters of that change.

On that unresolved contradiction rested much of the damage done to our movement particularly from the introduction of the Secondary Boycott laws on through the Accord and the Deregistration and Derecognition of the BLF, as the differences within the left of the organised labour movement were exploited to the advantage of employers and neo-liberal Governments. From the anti-Vietnam War era when a new wave of younger left activists came into the organised labour movement, young men such as John Cummins, John Cleary, Brian Boyd, John Loh and Dave Kerin, we generally were also members of left parties or at least associated with left traditions.

Younger comrades coming into building unions and specifically the BLF were open to radical notions and, given their experiences in the anti-war movement especially, they saw no separation between their union and social movement work. The Green Bans saw workers lay down a challenge to capitalism’s legitimacy. Unions like the BLF in Melbourne and Sydney and FEDFA in NSW put a question to their rank and file:

Will you stand in solidarity with your fellow workers not just over wages and conditions, but in the streets where they live will you take control out of the hands of employers and make decisions that are in the interests of communities, against the interests of building companies and other employers, when that solidarity is called upon? The rank and file answered a resounding “YES!”

“The union’s always had a social conscience. I’ve tried to get the union away from the narrow economic issues, to involve it in people’s actions.” – Gallagher (1)

THE NATURE OF THE GREEN BANS

By their nature, Green Bans are a poignant combination of crisis, participatory democracy and the workers’ right to equally determine all questions about their labour.

In other words the Green Bans raised the question of power within the economy. Unions in the past maintained that wherever power is at issue, then the resolution to the issue must be democratic. Where it is not, and unequal laws apply, then workers, the vast majority, reserve the right to strike.

Green Bans therefore are a form of strike which protect and defend communities and the environment.

In defending both communities and our natural and created environment, there is ever present an imagined future, informed often by past memories. Memories of better times than those we are currently experiencing inform a richer and more humane future. That vision starts with the act of solidarity involved in placing a Green Ban. Workers placing the Green Ban enrich their own lives by deepening their connection to others, acting upon the true meaning of the word compassion – to suffer with. Those who benefit from the ban, benefit not only physically. Perhaps more importantly they benefit from two intangibles: the expansion of their lives through solidarity and the effects upon their hopes and dreams from that which is saved. Those who would destroy parklands and low income inner-urban housing areas, because they believe in their own distorted definition of freedom, which rests upon the entrenched inequality of class privilege, were stopped by the Green Bans.

Workers placing the Green Ban enrich their own lives by deepening their connection to others, acting upon the true meaning of the word compassion – to suffer with. Those who benefit from the ban, benefit not only physically. Perhaps more importantly they benefit from two intangibles: the expansion of their lives through solidarity and the effects upon their hopes and dreams from that which is saved. Those who would destroy parklands and low income inner-urban housing areas, because they believe in their own distorted definition of freedom, which rests upon the entrenched inequality of class privilege, were stopped by the Green Bans.

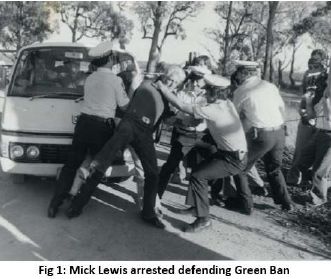

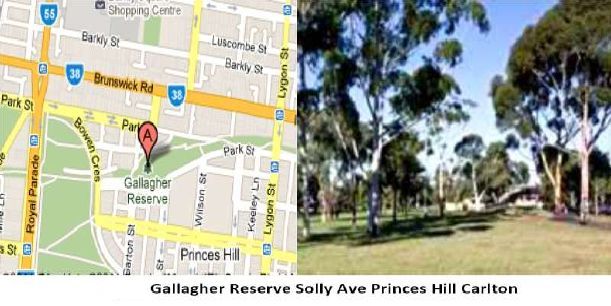

GALLAGHER RESERVE – THE FIRST MELBOURNE GREEN BAN

The first Green Ban, although still referred to as a black ban at the time in 1970, was the ban on work at what is now the Gallagher Reserve (in some documents referred to as the Hardy Gallagher Reserve, since the deregistration of the BLF in 1986) along the Solly Ave/Park St stretch in Princes Hill, Carlton, in Melbourne. Later that year the famous Kelly’s Bush ban was placed by the NSW branch of the BLF and FEDFA and, some months after that ban was placed, the name Green was attached to the ban. This distinguished it from an industrial black ban at the time.

That significant name change also ultimately provided the modern Greens Parties around the world with their name. Petra Kelly, the leader of a burgeoning environmentally focussed political party was so impressed with the Australian Green Bans that, when she was out here inspecting them, she asked Jack Mundey to return to Germany with her and tell the story. Upon Jack’s visit, that new political party proclaimed itself the Greens Party.

Bans placed and held by fighters such as Norm Gallagher and Mick Lewis over the Gallagher park ban were struggles for freedom, often won at the cost of the those fighters’ own freedom. In this case Norm did 14 days and Mick did 7 days inside to achieve the environmental rights of workers and their families to healthy, natural spaces for their spiritual renewal and a place to play for their kids.

QUEEN VICTORIA MARKET

From 1970 onwards pressure began to mount for the redevelopment of the Queen Victoria Market into a combined Trade Centre, office and hotel precinct. “However, public outcry prevented this and resulted in the Market being classified by the National Trust. Later, the Market site and its buildings were listed on the Historic Buildings Register. Queen Victoria Market survives today as one of the largest and most intact examples of Melbourne’s great nineteenth century markets.”

From 1970 onwards pressure began to mount for the redevelopment of the Queen Victoria Market into a combined Trade Centre, office and hotel precinct. “However, public outcry prevented this and resulted in the Market being classified by the National Trust. Later, the Market site and its buildings were listed on the Historic Buildings Register. Queen Victoria Market survives today as one of the largest and most intact examples of Melbourne’s great nineteenth century markets.”

“……but I think his word of ‘green bans’ helped to lift it.” – Gallagher on Mundey

Notice the descriptor ‘public outcry’? And the trajectory from there: onto the ‘Historic Buildings Register’?

Not a word about a union Green Ban. Yet if you talk to the older stall holders today they all know people who came before them who were involved in that period, and who are proud of the Green Ban. Since those days, through the seventies, eighties until now, many of us have all met, discussed politics, found jobs and shopped at the Vic Market every Saturday.

Our community is there; our kids grew up with the Market as a formative community influence; and importantly thanks to John Cummins, the Green Ban remains on the Vic Market. In the early 1990’s the stall holders approached Cummo to discuss yet another proposal to build inappropriately on Market land. Cummo reassured everybody that as far as he was concerned “The Green Ban was never lifted!” The Green Ban still holds and yet goes unacknowledged by the Market’s Administration. This ahistorical presentation of events must change.

Our community is there; our kids grew up with the Market as a formative community influence; and importantly thanks to John Cummins, the Green Ban remains on the Vic Market. In the early 1990’s the stall holders approached Cummo to discuss yet another proposal to build inappropriately on Market land. Cummo reassured everybody that as far as he was concerned “The Green Ban was never lifted!” The Green Ban still holds and yet goes unacknowledged by the Market’s Administration. This ahistorical presentation of events must change.

As With other parts of Melbourne’s history that were saved by the BLF, it would indeed be appropriate for an historical plaque to be placed at the Victoria Market that records the role of Norm Gallagher and the BLF in saving the site for posterity.

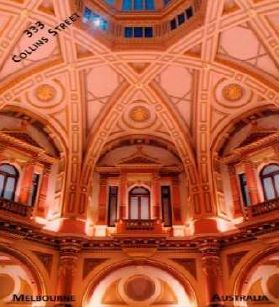

333 COLLINS STREET

333 COLLINS STREET

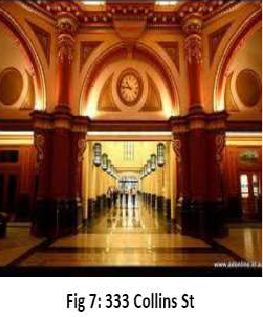

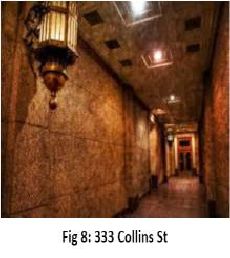

Sometimes the site of Green Bans involved places thought to be related to the centres of privilege. Banks and artistic pursuits that in times before the 1970’s not many workers could afford to engage with, for example. At 333 Collins Street “The crossed rib dome inspired by Italian Baroque and Moorish precedents, is considered one of the great Victorian era interiors of Melbourne, and was narrowly saved from demolition in the 1970s following public opposition led by the National Trust.

It was built for the Commercial Bank of Australia, and completed just as the 1880s financial boom collapsed – the bank had to close its ornate cast iron gates in April 1893 for a time to keep out desperate depositors at the height of the crisis. The original façade of the building was refaced in 1939, in turn replaced by the current podium level stone façade, the central section of which is a simplified version of the

It was built for the Commercial Bank of Australia, and completed just as the 1880s financial boom collapsed – the bank had to close its ornate cast iron gates in April 1893 for a time to keep out desperate depositors at the height of the crisis. The original façade of the building was refaced in 1939, in turn replaced by the current podium level stone façade, the central section of which is a simplified version of the

1893 original.” (3)

Number 333 Collins St in the heart of Melbourne’s financial district in the 1880’s when it was built, remains so today. However, and once again, if you went by comments quoted above we are asked to believe that the National trust led the opposition to its destruction and

Number 333 Collins St in the heart of Melbourne’s financial district in the 1880’s when it was built, remains so today. However, and once again, if you went by comments quoted above we are asked to believe that the National trust led the opposition to its destruction and

support for its regeneration. 333 Collins St was built by workers and owned by others. The wealth within its Commonwealth Bank of Australia walls was created by workers but owned by others. When those others attempted to demolish, it was it saved by workers, members of the BLF and led by Norm Gallagher.

“It was a team effort, and only teams win premierships. Dedication, discipline I think that it was a team effort. The union got its encouragement from the …people…They, in turn, got encouragement from the union. So it was a team effort.”- Norm Gallagher. (ibid)

THE REGENT

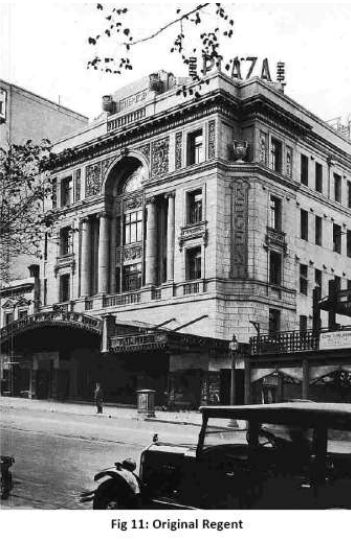

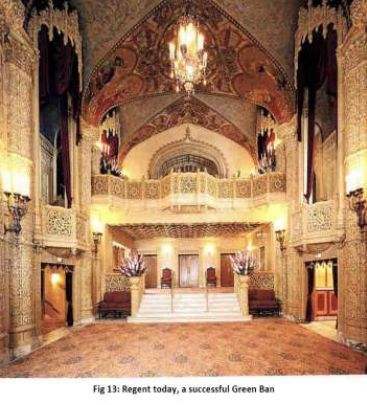

The opulent Regent theatre in Bourke St Melbourne was originally opened in 1929 to great acclaim as a cinema and also a

The opulent Regent theatre in Bourke St Melbourne was originally opened in 1929 to great acclaim as a cinema and also a

live theatre. The Regent had seating for 3000 people and was closed after being partly destroyed by fire in 1945. The theatre was reopened following restoration in 1946/47 and was operating until 1970 when it was closed by Hoyts’ theatres. The Melbourne City Council then purchased the Regent site for the purpose of selling it to a developer with plans for a high rise development. The protests that resulted from the planned demolition and redevelopment of the Regent also included an important approach to the Builders Labourers’ Federation for help in stopping the redevelopment. The ban subsequently placed on demolition of the Regent by Norm Gallagher and the BLF was the main factor that saved the theatre from destruction.

The protests that resulted from the planned demolition and redevelopment of the Regent also included an important approach to the Builders Labourers’ Federation for help in stopping the redevelopment. The ban subsequently placed on demolition of the Regent by Norm Gallagher and the BLF was the main factor that saved the theatre from destruction.

After remaining empty for 20 years, the Regent was restored to its former glory and was reopened as a live theatre in 1996. The Regent Theatre is today regarded a cultural asset for the City of Melbourne and is now protected by the National Trust and Victorian Heritage listing.

MELBOURNE CITY BATHS

The original Melbourne City Baths was opened on the present site on the c/s of Swanston and Franklin Streets in Melbourne in 1860. The baths were built in response to the needs of people who often never had any bath rooms or washing facilities in their homes, the original baths were closed in 1899.

The original Melbourne City Baths was opened on the present site on the c/s of Swanston and Franklin Streets in Melbourne in 1860. The baths were built in response to the needs of people who often never had any bath rooms or washing facilities in their homes, the original baths were closed in 1899.

The present Melbourne City Baths is situated on the same site as the original and was built in 1904 following a national competition for the best design. In 1970 the Melbourne City Council added the City Baths to the other list of Council property that was intended to be demolished and sold to developers.

Again it was Norm Gallagher and the BLF that answered the call from members of the public, and successfully placed bans on the proposed

demolition declaring the Baths to be “A workers pool”. Following the defeat of its proposed vandalism of another piece of Melbourne history, the Melbourne City Council later renovated the Baths at a cost of $4 million for the continued use and enjoyment of the people of Melbourne. The Baths are now on the Victorian Heritage register.

WINDSOR HOTEL

When the BLF and Norm Gallagher placed bans on the demolition of Melbourne’s Windsor Hotel in 1976, one of the grandest hotels in the world and a Melbourne icon was faced with the threat of demolition. Opened in Spring St Melbourne in 1883, The Windsor has been a world renowned hotel, ranked with the Waldorf Astoria and Plaza Hotels in New York, the Savoy Hotel in London and Raffles Hotel in Singapore.

When the BLF and Norm Gallagher placed bans on the demolition of Melbourne’s Windsor Hotel in 1976, one of the grandest hotels in the world and a Melbourne icon was faced with the threat of demolition. Opened in Spring St Melbourne in 1883, The Windsor has been a world renowned hotel, ranked with the Waldorf Astoria and Plaza Hotels in New York, the Savoy Hotel in London and Raffles Hotel in Singapore.

Important historically, the hotel was also the venue where the Australian Constitution was drawn up between Feb and March 1894. Since being saved by the BLF from demolition, the Windsor was later purchased by the Victorian Hamer Govt for the purpose of the Hotel’s preservation into the future.

The State Government was to later sell the hotel to private interests, and ever since, there has been intermittent controversy as to proposed new developments of the hotel. This controversy has also involved the handling by the Victorian Brumby Government of redevelopment applications.