by Wallace McKitrick

This is the first instalment of a three-part series that examines the literature of First People’s writers assertions of unceded sovereignty.

Introduction

This article arises from re-reading several important books published in the last 50 years along with recent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander writers’ pro-sovereignty critiques of the recent constitutional referendum proposition. Collectively they demonstrate that the assertion of unceded sovereignty of this continent’s First Peoples has been continuous for over 200 years and that self-determination has many dimensions, all of which are being practised today in ever-richer ways, despite institutional opposition.

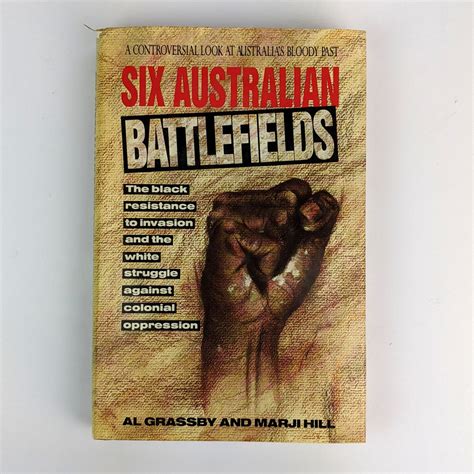

The books are Because a White Man’ll Never Do It by Kevin Gilbert (1973); Koori: a will to win by James Miller (1985); Six Australian Battlefields: the Black resistance to invasion by Al Grassby and Marji Hill (1988); Aboriginal Heroes of the Resistance: from Pemulwuy to Mabo edited by Paul Newbury (1999 edition); Treaty and Statehood: Aboriginal self-determination by Michael Mansell (2016); and Fire Front: First Nations Poetry and Power Today, edited by Alison Whittaker (2020).

We also draw on a paper by Professor Mary Graham, reports by two Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioners, Bangarra Dance Theatre’s Wudjang, and Tyson Yunkaporta’s latest book Right Story, Wrong Story: adventures in Indigenous thinking (2023).

PART ONE

Resistance to invasion and the settler state has never ceased

Six Australian Battlefields (1988) and Aboriginal Heroes of the Resistance (1999) don’t mince words regarding the British take-over of this continent. They demonstrate in detail that in military and legal terms ‘invasion’ is the accurate term, and the battles waged by First Peoples against the British army and its colonial auxiliaries are aptly called ‘the Hundred Years War’. Between them these two books cover the prolonged armed resistance by various peoples in every part of what is now called Australia.

No honest person can be in any doubt that the First Peoples of this continent, on grasping the intentions of these armed strangers, mounted vigorous resistance by every means available to them. Land was never voluntarily surrendered. Inalienable association with the lands and waters was never given up. Self-rule, sovereignty, in the context of subtle, defined relationships with the rest of the biosphere, was never renounced.

As many readers will be aware, Rachel Perkins’ three-part television documentary The Australian Wars (2022) takes up these themes with even greater geographical scope and with a powerful assertion of the urgent need for honest and just redress.

James Miller belongs to the Wonnarua people of (what in English is known as) the Hunter Valley of New South Wales. His stirring book Koori: a will to win deals initially with the Wonnarua’s years of first contact with the British military and settlers. He traces their 1810s-1820s uprisings in response to land theft and indiscriminate murder by settlers. Members of the Dharuk, Darkingung and Wiradjuri peoples joined forces with the Wonnarua in the later uprisings.

Later chapters in Miller’s book examine the renewed surge in organised activity by Kooris in the 1960s-early 80s. (He uses ‘Koori’ to apply to all First Peoples of this continent, rather than the anonymous English tag ‘Aboriginal’.) He describes the ‘enormously successful’ 1965 Freedom Ride through northern NSW organised by Charles Perkins to expose and confront the unlawful apartheid practices of many local governments, schools, hotels and commercial facilities. Miller calls this ‘the first battle in the long fight back’.

Other key events he summarises include the Gurindji people’s 1966 ‘walk-off’ from Wave Hill pastoral station controlled by the mighty English-owned Vestey Corporation, marking ‘the beginning of the modern land rights movement’; the 1960s-70s fight of the Yirrkala people of Arnhem Land for land rights against bauxite mining company Nabalco and the Commonwealth government; and the establishment of the ‘politically brilliantly timed’ Tent Embassy adjacent to Parliament House in Canberra on ‘Australia Day’ 1972. ‘Land rights’, wrote Miller in 1985, ‘have been the most consistent demand of Koori people since the late 1960s. … If Kooris can develop an economic or culture base in land over which we have freehold title, then we will not be as vulnerable to the racial whims of the dominant society.’

Over the nearly 40 years since Miller wrote those words, this vision has begun to be realised in small part. Sustained campaigns have prompted legislation in several states and territories under which some language groups or communities have control of portions of land and some aspects of governance. But many other Peoples and communities continue to seek land rights with substance. Indeed, in the 2020s there has been a further resurgence of campaigns for land rights or land compensation, and related economic rights. Economic rights are essential because self-determination doesn’t mean being left alone to conjure up a prosperous life out of thin air. It includes fruitful interaction with non-Indigenous enterprises and institutions on terms of mutual respect and reciprocity so that (for example) quality housing, health and safety services are mounted, under Indigenous direction, along with inclusion in wider regional economic development strategies in ways that reinforce Indigenous initiatives. (This point is amplified later in this article.)

Kevin Gilbert (1933-93)

The legendary Kevin Gilbert (Kamilaroi-Wiradjuri-Irish), writing in 1973, begins Because a White Man’ll Never Do It describing the warfare, poisoning, rape and massacres that were standard tactics of ‘Christian’ settlers in numerous regions. He summarises the authorities’ strategies of the following century: forced dislocation, division of kin groups from each other, compulsory servitude and ‘assimilation’ of children. Then he turns to self-determination issues in the current era.

His chapter ‘People speaking out’ discusses renewed initiatives by Aboriginal people during the 1940s-70s, including establishment of the first self-run legal and medical services, breakfast programs, Black Rights Committee and the Canberra Tent Embassy (in the planning of which Gilbert was involved). Later he traces the early 1970s development of Black writing and theatre, presciently seeing this as a realm of self-determination which would evolve into a range of powerful artistic endeavours promoting solidarity among Aboriginal people in city and bush.

His following chapter, ‘Labor’s Santa Claus’, examines the ALP’s history of half-measures, promises and betrayals. As a party primarily representing white people’s interests and constrained intrinsically by its service to large-scale pastoral and industrial elites, points out Gilbert, the ALP can never be relied on for whole-hearted support of Indigenous self-determination that includes fair reparation and self-run institutions wherever feasible. Nor, he says, have governments of any complexion offered ‘discreet non-dictatorial help’ unfettered by paternalistic control. (He also gives credit in the few instances where credit is due.)

In his Epilogue, Gilbert approvingly quotes a 1972 edition of Black National U including, ‘The only power Aborigines will ultimately have will be in their ability for political organisation independent of the institutions of government.’ In 1979 Gilbert was an initiator of the National Aboriginal Government under canvas on the selected site for the new Parliament House, demanding a sovereign treaty under international law and a Bill of Aboriginal Rights.

Land and waters have not been surrendered: self-determination remains a living goal

Aboriginal Heroes of the Resistance has a timescale from the 1790s resistance of the Eora to the first wave of invasion, through to the 1992 recognition by the High Court of the Meriam people’s Native Title in common law. This legal case had been initiated by the great Torres Strait Islander Eddie Mabo. The High Court judgement dismembered the fiction of terra nullius across the entire country.

Within this timescale, the book includes the 1940s Pilbara Strike, 1970s victories of the Victorian Aboriginal Advancement League in gaining freehold title for residents of Lake Tyers and Framlingham communities, establishment of the first Aboriginal Legal Service, then a Medical Service, in Redfern NSW (1970), the first hoisting of the newly designed Aboriginal flag in 1971, the campaign of Pitjantjara/Yankunytjatjara peoples in South Australia which won freehold title through a 1981 Land Rights Act, reclamation of Oyster Cove in Tasmania by palawa traditional owners in 1984, and the repossession of Uluru and Katatjuta by traditional owners.

The authors’ review of these hard struggles and what has been won through dedication, courage, perseverance and adroit campaigning, is inspiring. In the final pages of Aboriginal Heroes of the Resistance, Aboriginal lawyer Irene Watson is quoted: ‘The overwhelming logic is that the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nations have never ceded their sovereignty, and that the Nations that have survived 210 years of genocidal policies still assert their sovereignty.’ The section continues, ‘A valid constitutional doctrine of sovereignty in Australia can only be effected by a proper settlement … between non-Aboriginal Australians and Indigenous Australians.’ Later in this article, we look at some forms of treaty proposed by the sovereignty movement.