by Humphrey McQueen

Chapter 17 from Japan to the Rescue, Australian Security around the Indonesian Archipelago during he American Century

Heinemann, 1991, pp. 285-94.

… the nearest run thing you ever saw in your life.

… the nearest run thing you ever saw in your life.

Wellington recalling Waterloo

Linked to the conviction that the Imperial Japanese Army intended to invade the mainland of Australia in 1942 is the belief that only a US naval victory at the Battle of the Coral Sea, fought between 7 and 8 May that year, prevented invasion.

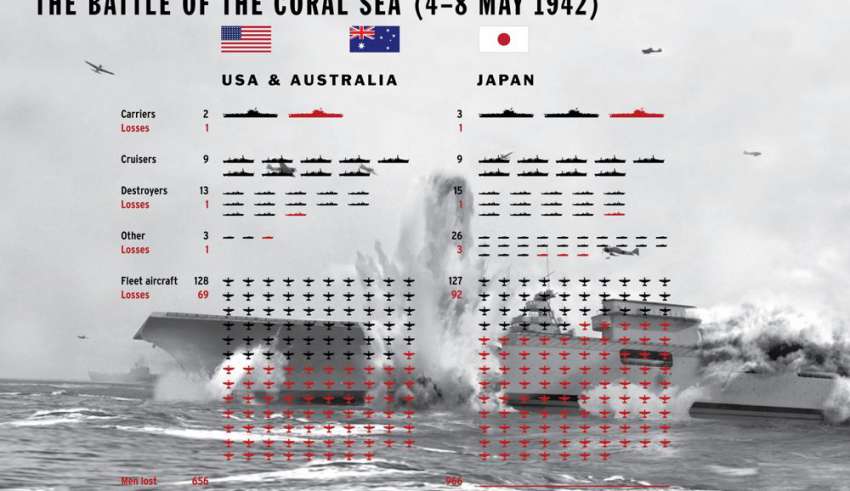

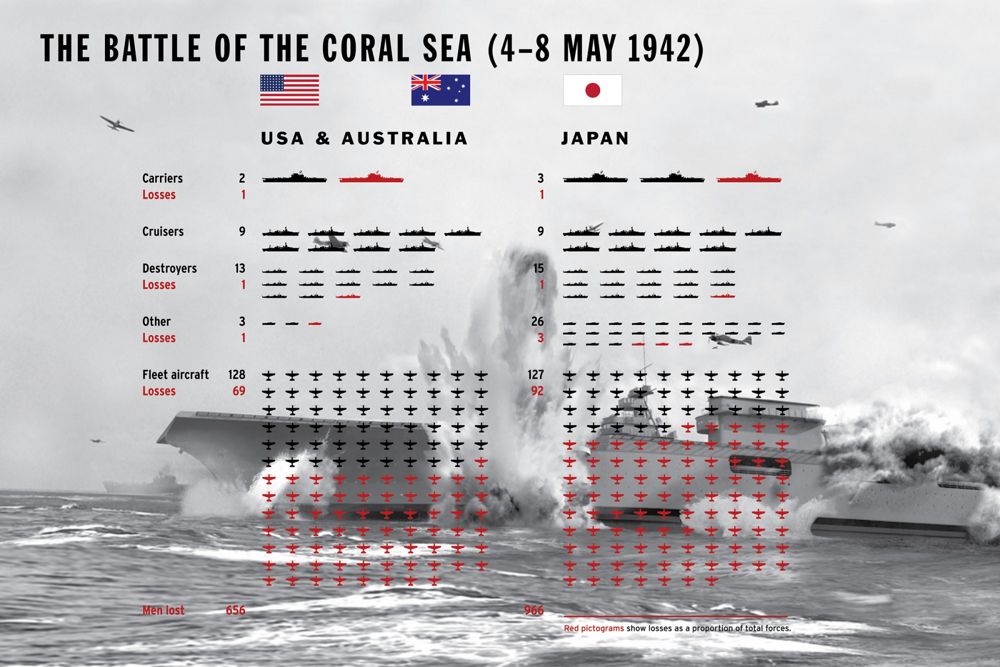

Despite the vaunted position that the Battle of the Coral Sea occupies in Australian consciousness, there is no clear-cut answer to who won that engagement. All that can be given with certainty are the losses suffered at the time. The US Navy lost the carrier Lexington, the destroyer Sims and the supply tanker Neosho; the carrier Yorktown was badly damaged but capable of repair after forty-eight hours intensive labour. (Spector, 1987: 162) The Imperial Japanese Navy lost the small carrier Shoho and had its fleet carrier Shokaku so badly damaged that it was not able to rejoin the fleet at Midway f our weeks later. Japan also lost irreplaceable planes and pilots. On the ships sunk or disabled, the Japanese narrowly won the Battle of the Coral Sea, a fact which Allied naval historians have never denied, equivocate though they do about the strategic significance of Japan’s win.

At the time, as is common, both sides declared a famous victory. The New York Times reported between seventeen and twenty-two enemy ships sunk or crippled and the remaining Japanese vessels put to flight with the Allies in joyous pursuit. On the other side, reports of a Japanese success roared through the entire Imperial fleet, nourishing the hubris that helped bring about the disaster at Midway on 4-6 June when four Japanese carriers were sunk. The material and psychological consequences of the Battle of the Coral Sea were greater at Midway than at Moresby. Excessive claims about the damage done were encouraged by the un-precedented nature of the battle in which the opposing ships never sighted each other. All the attacks were carried out by seaborne aircraft; each pilot claimed that his bombs had sunk a particular ship, thus multiplying the reported damage. Believing the Lexington destroyed at Peal Harbour, the Japanese wrongly identified the carrier they hit at Coral Sea as the Saratoga. (Fuchida and Okimiya, 1958: 98 & 100)

Australian newspapers reproduced press releases from MacArthur’s headquarters about massive Japanese losses: ‘one aircraft carrier, one heavy crusier, one light cruiser, two destroyers, four gunboats and a supply ship’, as well as another carrier probably sunk and four more ships damaged. A slightly more accurate account became available four days later but was not published. The extent of US American losses was also kept from the public. On 13 May, the Advisory War Council in Canberra summed up the results of the Battle of the Coral Sea as ‘rather disappointing’ because even advance information had not allowed a sufficient concentration of Allied forces to achieve ‘complete victory. As it was, an opportunity to inflict losses on the enemy was lost’. (quoted Gill, 1968: 55)

The Japanese high command, while exhilarated by reports of their latest success, also felt that its fleet should have achieved more. Despite low fuel reserves, the Japanese ships were ordered to put about and resume their attack on the US vessels that had cleared the area – the reality at the day’s end being exactly the opposite of the report in the New York Times. (Toland, 1970: 324)

Although the balance at sea ran slightly in favour of the Japanese forces, judgement of the engagement’s longer-term implications requires careful delineation of pre-battle objectives and post-battle capabilities. Allied commentators have based their claim of a ‘strategic victory for the Allies’ on the failure of the Japanese fleet to escort an invasion force to Port Moresby. On that point there can be no disagreement. The Coral Sea was the first time in six months of fighting that a large-scale Japanese advance had been checked in combat. Its impact on Allied morale cannot be doubted, no matter how exaggerated the evidence on which that stimulus was based.

If the significance of the Coral Sea battle is to be judged by Japan’s capacity to attack Port Moresby, a longer perspective is required. A seaborne invasion of Moresby scheduled for March had been postponed because only land-based air support had been available to deal with the US task force sighted in the area. After the Coral Sea, the seaborne attack was gain postponed, not cancelled. When the defeat at Midway on 4-6 June made the resumption of a seaward invasion on Moresby ever more improbable, the army responded by driving over the Owen Stanley Ranges. By 16 September, ill-equipped Japanese had pushed the Australians back to within thirty miles of the coast. If occupation of Moresby held the key to Australia’s security, that risk was not removed until 26 September when the Japanese army reluctantly pulled back its starving and exhausted survivors. (MacArthur, 1966: 165)

Conclusions about the strategic outcome of the Battle of the Coral Sea are muddied by the Australian assumption that the Japanese command was planning an invasion of continental Australia for which the occupation of Moresby is seen as a necessary prelude. An invasion had been rejected in March. When the Japanese regional command sent its force towards Port Moresby from Rabaul on 4 May 1942, it had long-term objectives quite different from those still supposed by many Australians. For Admiral Inoue, the capture of Port Moresby was one more step towards establishing a line of interdependent bases form the Solomons to the Netherlands East Indies. Inoue feared that, without this perimeter under his control, land-based aircraft could be launched form Moresby against Rabaul or Truk. The security of Japanese forces would be further enhanced by using that chain of airfields to make interdictory raids on northern Australia and into the Coral Sea to preempt US assaults. Japanese occupation of Moresby would have increased the intensity of air attack on north Queensland to prevent a built-up of US and Australian forces for a counterattack. Inoue’s aim in launching the offensive of 4 May was to fill gaps in his perimeter. He was heading east and west, not south.

If the events of 7-8 May are seen in light of Japanese objectives, and not in terms of Australia’s fears, the return of transports to Rabaul is not so clear cut a strategic reversal as allied writers have wanted to believe. Withdrawing the transports late on 7 May preserved their troops for the landward assaults during September. Even the catastrophe at Midway did not stop Japanese naval victories in the south-west Pacific since the Imperial Navy won the Battle of Savo Island in August and the Battle of Santa Cruz Islands late in October 1942. (Toland, 1970: 362 & 409)

Japan’s push on Moresby did not end early in May 1942 but continued with a two-pronged plan to advance by land and by sea. As far as the Japanese strategists were concerned, a seaward invasion had been delayed only until the Coral Sea could be cleared of Allied shipping. That day never came.

The complexities of assessing the outcome in the Coral Sea continue to bedevil scholarship. One venerable specialist, Norman Harper, managed to get almost nothing right: ‘The Battle of Coral Sea on 8 May 1942 checked the southward thrust of the Japanese navy and ended the danger of a sea attack on the Australian mainland’. (Harper, 1987: 112) By restricting the date of the engagement to 8 May, Harper excluded the sinking on 7 May of the light carrier Shoko, the loss of which brought on the decision once more to postpone the invasion of Moresby. It is difficult to understand what Harper meant by the threat of a sea attack on the Australian mainland. An invasion had been rejected by the Japanese in March, while the midget submarines raid on Sydney and the shelling of Sydney and Newcastle took place four weeks after Harper claimed ‘the danger of a sea attack’ had ended. (Long, 1973: 193)

When distinguished professors produce such fallacious summaries, it is hardly surprising that the popular press is often guilty of reconfirming the public in the morale-boosting view put out in 1942. One reason for this confusion is that the propaganda uses of a US ‘victory’ did not end with the defeat of Japanese in 1945 but flourished after 1950 as part of the Cold War. They provided an ideological foundation for the ANZUS alliance and for our hosting the US military communications and spy bases. At the core of this propaganda have been the Coral Sea Week celebrations.

THAT WEEK THAT WASN’T

The initial Coral Sea Week celebration in 1946 combined a fund-raising charity ball with an invited luncheon address by the Australian-American Association’s president, R.G. Casey, anti-Labor ex-politician and first Australian minister to Washington in 1940. The Association also began educating the general public who ‘even today do not seem to realise’ the importance of the battle that ‘saved Australia from becoming one the bloody and ravaged battle fields of the war’. Australia’s historical consciousness had to be reminded of its debt to the US of A through services in schools, displays in shop windows and the flying of flags from public buildings. An editorial in the conservative Melbourne Argus (8.5.46) recognised that although ‘memories are short’, commemorating the Battle of the Coral Sea would ‘encourage Anglo-American cooperation in shaping the future.’

Coral Sea commemorative celebrations were the creature of the Australian-American Association, which had been formed in 1936 to encourage anti-isolationist forces in the US of A. After the war the Association again tried to keep the US involved in global security as a backstop for the battered British Empire. The Association’s president, Chief Justice Sir John Latham, noted in a 1951 letter to Prime Minister Menzies: ‘… it is of very great importance … that … the United States-Australian, and inferentially Empire relations should be given official acknowledgement at least once a year and that Coral Sea Week is the best possible occasion to do this’. (AA CRS 463/17) Until the 1950s, the Association’s supporters could avoid choosing between Britain and the US of A. For Australia, the Association aimed to secure permanent US protection against aggression from a revengeful and rearmed Japan, communist aggression and the chaos surrounding de-colonisation in India and Indonesia.

Commanded by one of the founders of the Australian-American Association, Sir Keith Murdoch, the Melbourne Herald fired a broadside in the 1946 campaign to establish the facts about the Coral Sea battle in Australia’s popular memory. For the paper’s ‘Special Correspondent’, the Japanese had aimed to take Port Moresby before heading ‘south for Townsville and the coastline north of Brisbane. Neither task, the Japanese have admitted since, was reckoned as difficult.’ After this imaginative beginning, the writer gave strategic direction of the sea battle, not to Admiral Nimitz, but to General MacArthur who had long before been fixed in the minds of Herald readers as the savior of Australia. (The battle was fought just inside MacArthur’s command boundaries but by ships under Ninitz’s control; MacArthur complained that operational cooperation had been unsatisfactory.) A few paragraphs later, Australia was saved from invasion after the Japanese lost ‘one big aircraft carrier, three heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, three destroyers, five transports, and other small vessels, in addition to many damaged.’ (Herald, 4.5.460 This almost entirely erroneous account harked back to the original misleading reports for its ‘facts’.

Coral Sea Week organisers gained precious little support from Prime Minister Chifley who declined to have Commonwealth Government buildings fly flags. Questioned in the House on the eve of the 1947 anniversary. Chifley again avoided involvement, stressing that ‘Remembrance Day and Anzac Day have been specially dedicated each year to commemorate our participation in the world wars.’ (CPD, 7.5.47)

Unlike Anzac Day, which it closely followed on the calendar, Coral Sea Week was celebratory rather than solemn, aiming to provide the best night out of the year. Gallipoli had been a heroic defeat where failure heightened the appeal to nobility, a sentiment found also in Bushido, Japan’s code of chivalry. (Morris, 1976) No advocate of Australian military greatness ever pretended that the Turks had withdrawn. In contrast, the Coral Sea story has always depended on oversimplification, misinformation and deception. Gallipoli’s installation as the focal point of Australian memories of the Great European War had been assisted by its being the first major engagement of Australian soldiers anywhere. Even if the Battle of Coral Sea had achieved what its promoters claimed and saved Australia from invasion, its position as the focus for memories of the Second World War would still have faced competition from other engagements and campaigns, from Tobruk to Kokoda. Moreover, Australian participation in the Coral Sea was marginal. During a fight where the opposing ships never came closer than 240 kilometers there was not much that cruisers like HMAS Hobart and Australia could do. From the standpoint of Australian valour, the Battle of the Coral Sea was a non-event. This passivity made the Coral Sea the ideal clash of arms through which to demonstrate how dependent Australia had to be on the US military.

Although Australian warships had played next-to-no part in the fighting, the Naval Board recognised that annual Coral Sea celebrations would give their service a prominence not available from Anzac legends. Chifley’s reluctance to promote Coral Sea Week came out of a treasurer’s suspicion that the Naval Board’s enthusiasm suited its campaign to get even more money. (AA, CRS 463/17) During 1949, the Chifley government finally got caught up in the celebrations through a curious process that betrays the fine Italian hand of R.G. Casey and his manner of wielding influence. Having had direct outside requests rebuffed, Casey asked Labor Immigration minister Arthur Calwell, always proud of his Pennsylvania ancestry, to approach Chifley informally with a proposal to invite a US naval unit Australia for Coral Sea Week in 1950. After Casey intimated to several ministers that he already had the support of their colleagues, cabinet decided on 4 July 1949 to issue the invitation. (AA, CRS 463/170 Failure to do so would not have looked good in an election year when Casey was Liberal Party president and a candidate.

Before the close of 1949 the strategic topography of post-war Asia changed with Mao Zedong’s proclamation of the People’s Republic of China, the Soviet Union’s testing of an atomic bomb and the withdrawal of the Dutch from all of their East Indies territories except Papua Barat. As a result, Japan ceased to be the despised enemy and was on its way to becoming a de facto ally of the US of A. (Rotter, 1986) US authorities remained shy of alliances that limited their freedom of response in the Pacific. Hoping to rebind US armed might to Australia’s defence, the Menzies government signed the Peace Treaty with Japan as one strand of a maritime alliance anchored by the ANZUS Treaty. On 22 January 1952, Sir Percy Spender, an architect of ANZUS and by then Australia’s Ambassador to Washington, assured the Secretary of State that Coral Sea Week ‘celebrations this year will derive added significance from the recent signature of the Tripartite Security Pact.’ (AA, CRS 57/314)

R.G. Casey became Minister for Supply and Development in December 1949 and soon rallied cabinet colleagues around government involvement in Coral Sea Week celebrations. A State Department assessment of the new Australian government described Casey as ‘outstandingly friendly’. (quoted Pemberton, 1987: 7) Casey’s personal relationships with prominent US citizens had begun at Cambridge before the Great War when he found them easier to get along with than the British students; he was charmed to breakfast with ‘the richest man of his age in the world’, Averell Harriman. (Hudson, 1986: 23) When Casey went to Cairo in 1942 he left his children in the care of Dean Acheson, Secretary of State when the ANZUS Treaty was negotiated in 1951. As Australia’s External Affairs minister from 1951 to 1960, Casey leant towards the US more than did Prime Minister Menzies, as evidenced by their split over Suez in 1956. (Martin, 1989)Propaganda was never far from Casey’s thoughts and he used ASIO to try to censor the letters to the editor published in the Age. Promotion of the Coral Sea Week celebrations was one more instance of what his biographer coyly describes as Casey’s lifelong ‘interest in intelligence and counter-subversion’ (Hudson, 1986: 50), detailed revelations of which (Toohey & Pinwell, 1989) led to the sanitizing of his unpublished diaries in the National Library. (Age, 2.8.89)

The change of government in Canberra facilitated switching the Chifley invitation – declined by the US fleet – into a request for the participation of the commander-in-chief of the US Pacific Fleet, Admiral P.W. Radford, as the first designated Coral Sea guest. The quickened significance of the Coral Sea celebrations for Pacific strategy was underscored by official conversations between Admiral Radford and the Australian ministers for the Navy and for Air concerning the naval aviation equipment required for maritime surveillance from the mid-Indian Ocean across to the far-west Pacific. Admirals Radford and Collins finalized this network at Pearl Harbour in February 1951 to provide the ANZUS partners with their only continuing operational arrangements. (Young, 1988) Radford sat with members in the House of Representatives to hear Menzies say that the US sailors were welcome at any time in any Australian city, town or countryside.

In 1948, with New York’s Cardinal Spellman as its unofficial quest of honour (NLA, MS 6150), the Association had received approval in principle for the erection of a memorial somewhere in Canberra to commemorate the US contribution to the defence of Australia. In 1950 Menzies launched an appeal for £50,000. Before the 80-metre column was erected, the government and public contributed £113, 000 to the Australian-American Association’s campaign. The ceremony marking the start of construction on 10 March 1953 coincided with discussions for a draft treaty of friendship with the US of A: care was taken to have both negotiating teams attend to impress the US side with the depth of Australian gratitude. (AA, CRS A 462/1) Queen Elizabeth II unveiled the finished memorial on 16 February 1954, her presence distracting from how the US of A had displaced Great Britain as Australia’s greatest and most powerful friend. Four years later the government reinforced this connection by deciding to erect the Australian Defence Department offices beneath the US eagle clasping the globe in its talons.

Through a web of personal and political friendships, the Australian-American Association acted as if it were a section of the Department of External Affairs, selecting the guest and organising his itinerary while the government picked up the bill. (AA, CRS 463/17) Its 1952 guest embodied the anti-communist twist given to what had been a battle in the war against fascism. General Eichelberger had commanded US troops in Siberia, fighting along the Japanese army during the 1918-21 wars of intervention to overthrow the new Bolshevik regime. After retiring as Eighth Army commander in 1948, Eichelberger joined forces with the American Council on Japan (ACJ), which had been formed under the aegis of Newsweek and its principal shareholder, US Secretary of Commerce Averell Harriman, to oppose breaking up the Japanese monopolies. Eichelberger became ‘the first and foremost promoter of Japanese rearmament’, arguing ‘that a large army in Japan … “would doubtless act as a powerful deterrent to Soviet expansion in the West” …’. Employed as a consultant with the Assistant Secretary of the Army, he ‘served as the principal liaison between the ACJ and top Washington officials., such as George F. Kennan, who adopted Eichelberger’s ideas in drafting National Security Council document 13/2 of October 1948. That document proposed that a remilitarised and economically revived Japan become the basis for US containment along the ‘Great Crescent’ through Indonesia and around to India. (Schonberger, 1977: 343-8) Eichelberger’s press interviews in Australia were silent on the future of Japan. As ex-commander of the force that had retaken Buna he emphasised that ‘New Guinea should be built up into a bastion of Australian defence’. (SMH, 27.4.52)

As a propaganda focus for justifying Australia’s ‘declaration of dependence’ (Barclay, 1985: 79) to the Australian people, Coral Sea Week found its greatest success. When protests against Australian military involvement in Vietnam increased during 1966, Defence Minister Fairhall assured the cabinet that ‘people won’t dare to throw away the value of the USA alliance when they recall the Coral Sea Battle’. (Howson, 1984: 218)

Although circumstance has changed several aspects of Coral Sea Week celebrations, their one immutable element has been the inability of the media to report accurately what happened on 7-8 May 1942. Because ‘memories are short’, the press continues to publish feature articles to remind the public of what the Coral Sea meant. Sydney’s Daily Telegraph combined its 1984 commemoration of the battle with homage to Orwell’s Ministry of Truth wherein Oceania’s endless victories over Eurasia were manufactured. Readers learnt that ‘the Japanese fleet, with much heavier losses, was finished. The enemy’s surviving ships were in full retreat’. (7.5.84) Far from being in full retreat , ‘the Task Force consequently turned south again and sought to reestablish contact, without success, until sundown on 10 May’, (MacArthur, 1966: 138), that is, two days after the US fleet had withdrawn.

Popular reports have rarely relied on official Allied writings. Even when the Canberra Times got the outcome of the sea battle correct, it drew a false conclusion about the battle’s wider significance by claiming ‘a strategic victory for US and Australian forces, with Australia secured against Japanese attack.’ (4.5.88) If ‘attack’ means invasion, then that was never part of the Japanese purpose; it ‘attack’ means running assault who, if not the Imperial Japanese Navy, shelled Newcastle and Sydney four weeks later?

Perennial disregard for the evidence has enabled the promoters of the Coral Sea Week celebrations to snatch ‘victory’ from the gums of what, charitably, might be described as a ‘near run thing’ for the Allies. The lasting victors have been the US State and Defence Departments, which have been able to treat Australia as a suitable piece of real estate for military bases and from which to recruit troops for wars against Korea and Vietnam. Canberra’s rationale for the US-Australian alliance has always been that ‘they saved us’ from the Japanese and that we should be gratefully respectful so that the US of A will deliver us from future enemies. Throughout this charade, falsification of the objectives and outcome of the Battle of the Coral Sea has been invaluable.

For a detailed account of Coral Sea Week celebrations focused on the city closest to the battle, Cairns, see my ‘Balls and Receptions: Remembering the Battle that Saved Australia, 1942-1991’, The Battle of the Coral Sea 1942, Conference Proceedings, Australian National Maritime Museum, 1993, pp. 134-52.

For the official reaction to the chapter in Japan to the Rescue see Tom Frame’s contribution to this conference, pp. 153-160.

Abbreviations

AA Australian Archives

CPD Commonwealth Parliamentary Debates

NLA National Library of Australia

References

Barclay, Glen St John (1985), Friends in High Places, OUP, Melbourne.

Fuchida, Haruhiro and Masatake Okumiya 91958), Midway, Ballantine, New York.

Gill, Hermon G. (1968), Royal Australian Navy, 1942-1945, Australian War Memorial, Canberra.

Harper, Norman (1987), A Great and Powerful Friend: A Study of Australian-American Relations Between 1900 and 1975, UQP, St Lucia.

Howson, Peter (1984), The Life of Politics, Viking, Ringwood.

Hudson, W.J. (1986), Casey, OUP, Melbourne.

Long, Gavin (1973), The Six Years War: A Concise History of Australia in the 1939-45 War, AWM, Canberra.

MacArthur, Douglas (1966), Reports of General MacArthur: Japanese Operations in the South-west Pacific Area, volume 2, Part I, US Government Printing Office. Washington DC.

Morris, Ivan (1975), The Nobility of Failure: Tragic Heroes in the History of Japan, Holt, Rinehard & Winston, New York.

Pemberton, Greg (1987), All the Way, Allen & Unwin, Sydney.

Rotter, A.J. (1986), Prelude to Vietnam: Origins of the American Commitment in South-east Asia, Cornell, Ithaca.

Schonberger, Howard (1977), ‘The Japan lobby in American foreign diplomacy, 1947-1952’, Pacific Historical Review, 46 (3): 327-59.

Spector, Ronald H. (1987), Eagle Against the Sun: The American War with Japan, Penguin, London.

Toland, John ((1970), The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall and the Japanese Empire 1936-1945, Random House, New York.

Toohey, Brian and Bill Pinwell (1989), Oyster: The Story of the Australian Secret Intelligence Service, Heinemann, Melbourne.

Young, Thomas-Durell (1988), The Diplomatic and Security Implications of ANZUS Naval Relations , 1951-1985, Strategic and Defence Studies Centre Working Paper No. 163, ANU, Canberra.