By Art Museum Workers

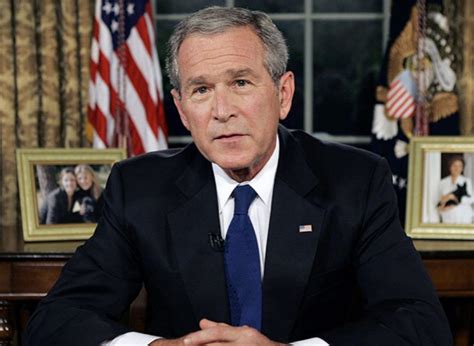

On 19th of March 2003, then US President George W. Bush addressed the nation

that “American and coalition forces are in the early stages of military operations to

disarm Iraq, to free its people and to defend the world from grave danger.” On the

20th of March, then Australian Prime Minister John Howard announced that Australia

was to be involved in this coalition of military forces – “The Government has decided

to commit Australian forces to action to disarm Iraq because we believe it is right, it is

lawful and it’s in Australia’s national interest.” Twenty years later, we can reflect on

the results of the campaign “to defend the world from grave danger” with knowledge

of the fact that the lawfulness of the invasion was baseless – there were no weapons

of mass destruction in Iraq. As to whether it was “right” and in the national interest,

then perhaps it’s up for Australians themselves to consider the value of fighting

unjust wars in support of the USA.

The first decades of the 21st Century world have been completely shaped by

the so-called War on Terror. Just as the ideological ‘never forget’ slogan was utilised

by US war-mongerers following the attacks against the USA on September 11th, the

world must never forget the western coalition force’s catastrophic exit from

Afghanistan on 15th August 2021. The world also ought never forget how popular

support and opposition to the War on Terror took various political forms, such as

through the Stop the War Coalition, where activist groups and unions worked

together in opposition to the War on Terror. Anti-war sentiment was also carried

through less organised and more mainstream voices, where views towards our

military alliance with the US caused rifts within society and throughout popular

culture (for instance, recall even the backlash following Anthony Mundine’s criticism

of Australia’s support of the US operation in Afghanistan). The fact remains that

Australia has always followed the military decisions of foreign powers in the interest

of the British empire and US imperialism. Accordingly, anti-war sentiment and the

necessity for national independence can be identified as two of the fundamental

components of an ongoing people’s movement that draws together Australia’s

various voices of dissent.

Looking back over the twenty years since the announcements of the Iraq

invasion, it’s important to note that the people of Australia were not simply duped

masses who were unaware of the unjust basis of the conflict. Guerilla cultural

expressions of anti-war sentiment occurred contemporaneously with Howard and

Bush’s war announcements. Perhaps most notably, on the 18th of March, in the lead

up to Bush’s war broadcast, anti-war activists Dave Burgess and Will Saunders

climbed the Sydney Opera House to paint ‘NO WAR’ on the cultural landmark’s

largest sail. In a recent interview, Burgess said that while painting the slogan, he was

“just thinking about the imminent conflict and the number of people who were going

to die and how global politics would be changed forever for the worse as a result.”

Although one may cynically dismiss Burgess as a riled-up and reckless pacifist,

history has justified his concerns and actions. No official work of culture could have

achieved the immediacy and urgency of the anti-war message that drove Burgess to

climb the iconic Opera house — a shrine to Australian modernism. During his trial

Burgess said “This was a once-in-a-lifetime situation that we were trying to stop

some terrible thing happening by whatever means were at our disposal [sic]. Only

that building could have conveyed the message to the rest of the world that the

majority of Australians were against the war at the time”.

Aside from these grand stunts, there were less overt and spectacular

expressions of popular dissent and frustration concerning the dire geo-political

situation at the beginning of the century. As an integral part of counter-cultural

struggle, music served as an effective means of voicing anger against imperialist

wars. Australia’s punk and alternative music scenes were significantly vocal about

Australia’s involvement in the War on Terror, with some more popular examples

being Adelaide pop-punk band Kisschasy’s classic video clip for Opinions Won’t

Keep You Warm At Night and the punk compilation Rock Against Howard, which was

an Australian offshoot of the Rock Against Bush project. More grass-roots and

underground music cultures were also developing expressions of 21st century

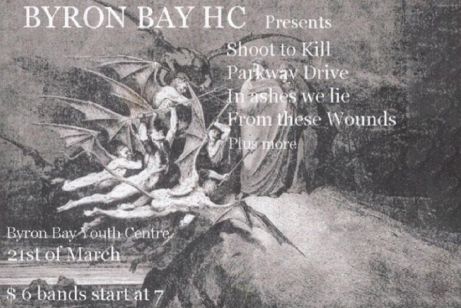

political dissent. On the night following Howard’s announcement of Australia’s

involvement in another US war, metalcore band Parkway Drive performed their first

gig. Far away from Canberra, Washington DC and Baghdad, these five angsty

teenages took to the stage of the Byron Bay Youth Centre and marked the beginning

of one of the most popular and successful bands to develop out of the contemporary

Australian music scene. While the band’s commercial success story is widely

celebrated by official media (for example, see the ABC’s recent episode of Australian

Story that’s devoted to the band), what’s most significant is that the band’s roots

were formed within a set of social and cultural conditions where hopelessness,

confusion and frustration towards the world were common enough sentiments to

develop into an influential sub-culture of hardcore music.

During the 2000s local hardcore/punk gigs were a regular occurrence within

Australia’s regional areas, especially throughout the east coast where

suburbanisation and uneven industrial development had produced conditions for

angry young people to seek creative ways to vent their frustrations. The gradual

proliferation of home computers and internet connections had allowed for networking

through shared musical and cultural interests on social media platforms like

MySpace. Young people shared pirated music and saved up for cheap musical

instruments through casual work at fast-food chains and supermarkets. Bands

rehearsed in parents’ garages, made demo recordings and performed self-organised

gigs at local youth centres.

For those unfamiliar with the subgenre and culture of hardcore, it is an

aggressive off-shoot of punk music (short, fast songs performed with hard-hitting

drums, distorted guitars and screamed vocals). Lyrics are focused on social issues

and the troubles faced by working/middle class youth. The subgenre of metalcore

fuses these hardcore elements with themes that are common to the metal genre,

such as gothic and romantic themes in lyrics, expressive instrumental performances

and heavy use of symbolism. Building on hardcore’s realist focus on concrete

experiences that shape suburban life, metalcore imports the larger-than-life,

melodrama and theatrics of metal to heighten the aggression of hardcore. In their

early years, the appeal of Parkway Drive stemmed from their hardcore roots, before

the band’s commercial success further developed with their more exclusive embrace

of metal.

It can be assumed that it was during Parkway’s first performance that the

band debuted their song “I Watched” (such an assumption stems from the fact that

this song would go on to be included on the band’s first release of recorded music in

May 2003). Considered in relation to the broader social and political conditions in

which both the War and Terror and Parkway Drive formed, the performance of “I

Watched” is significant. Aside from being a document of angry teenage boys in the

garage, the song’s lyrics express a profound confusion and despair amind the

post-9/11 and emergent War on Terror period:

In an instant

this world’s hate

engulfed all tenfold.

Hate.

I watched the birth

of tomorrow’s catchphrase

— Terror —

as the sky came crashing down.

True terror now assumes a human form:

Suspicious minds

pointing fingers

still ignore.

Suspicious minds

tear at innocence.

I watched the sky burn.

As the ashes fell

Time stood still

“I Watched” encourages listeners to critically reflect on the consequences of the

September 11 attacks against the USA and the fear that was manufactured by

governments and media. Hate had resurfaced as a real driver of events in the world;

the attacks expressed a violent hatred towards US imperialism, and, in turn, the West

opportunistically justified its own violent hatred through war against its perceived

enemies. Most Australians would remember the fear of terror that the Howard

government propagated through its $15m campaign titled, “Let’s Look Out for

Australia”, where advertisements informed us all to be “be alert, not alarmed”.

Encouraging suspicion towards everyday people, rather than suspicion towards the

government whose foreign policy decisions directly lead citizens to be at the risk of

violence (which lead to the occurrence of the Bali bombings, which were in direct retaliation to Australia’s military support of the USA and political interference in

East-Timor). The narrative regarding the threat of terror was succinctly outlined by

Parkway Drive in “I Watched”, as government propaganda had created an image

where “true terror now assumes a human form”. Anti-western “terror” served as a

scapegoat to point fingers towards and to blame as an evil cause of harm against

Western “innocence”. Parkway Drive turned this perspective upside down in order to

present the “suspicious minds” created by political messaging and advertising as the

true agents of terror.

“I Watched” provides a relatable perspective for young Australians who grew

up witnessing the development of a post-Cold War fear against a new enemy. The

simplified vision of geopolitics held that Soviet communism was no longer the

primary threat for the USA aligned world, and that a new enemy had emerged in the

form of religious fundamentalist terrorists and non-western ‘authoritarian’ states. In

2004, the year following Parkway’s first performance, the band released their first

collection of songs on an EP titled “Don’t Close Your Eyes”. This release included

their iconic song “Smoke ‘Em If Ya Got ‘Em”, the lyrics of which express a bleak

assessment of the 21st Century world:

Thoughts replaced by placid romance

Without movement, I can’t escape.

Searching through the static

twisted and torn inside of

such blinding visions of destruction.

So I have to question,

was this in the master plan?

‘Cause now a broken future’s all that we hold.

Broken.

Our broken future is all that we hold.

Our day draws

to its close.

Dusk

Washes away.

Integrity now bleeds away

As tired hearts are left to drain.

Do you see their faces when you fall asleep at night?

Now they’re nothing more than blood stained memories.

Blood stained memories.

Fuck it all.

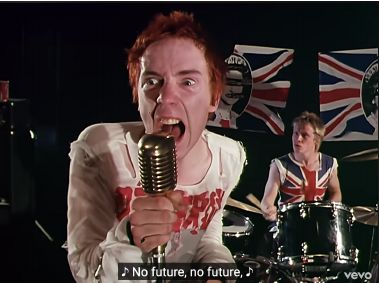

In “Smoke ‘Em if Ya Got Em”, Parkway updated the pessimistic, punk-era outlook of

“no future” in response to the world of the War on Terror, where it seems that a

“broken future is all that we hold”. This hopeless perspective isn’t simply the view of a

depressed and melancholic individual – Parkway Drive provide a sober assessment

of reality shaped by war, media and politics: “twisted and torn inside of / such blinding

visions of destruction. / So I have to question, / was this in the master plan? / ‘Cause

now a broken future’s all that we hold.” Anyone who grew up surrounded by the

“blinding visions of destruction” that accompanied the so-called Operation Shock and

Awe ought to have questioned the US-led western “master plan” of fighting for peace

and freedom. Even though this reality drives us to want to give up and scream “fuck it

all”, these are our blood stained memories that mustn’t be forgotten.

Screenshot from The Sex Pistols – God Save the Queen (1977)

Screenshot from Parkway Drive – “Smoke ‘Em If Ya Got ‘Em” (2004)

Unfortunately, the broken future foretold by Parkway has become our broken

present; twenty years on from Parkway’s beginnings and the calamitous War

on Terror, Australia continues to commit its full support for US imperialism. On the 14th

March 2023, the anglosphere once again expressed its defence allegiance as

Australia, the UK and the USA — AUKUS — announced the plans for the production

and joint-operation of nuclear-powered submarines. Just like the baseless military

threat of weapons of mass destruction that was used to justify the invasion of Iraq,

the protection of US economic dominance and the “rules based order” against China

is being used as the new excuse for war.

Coincidentally, on the weekend following this AUKUS announcement,

Parkway Drive also performed in Australia for the first time in years. This time, the

band didn’t perform at the Byron Bay Youth Centre to a crowd of a few teens, rather

they played to tens of thousands of people at sold out crowds as part of a touring

metal music festival “Knotfest” (an event owned and operated by US band Slipknot).

Unfortunately, neither “I Watched” nor “Smoke ‘Em If Ya Got ‘Em’ were performed,

despite the continued relevance of their lyrics. Following the disastrous War on

Terror, there is a desperate need for artists in the present AUKUS-era to produce

relevant works in forms that connect popular dissatisfaction with the world to the

ongoing military actions by imperialist powers.