by Humphrey McQueen

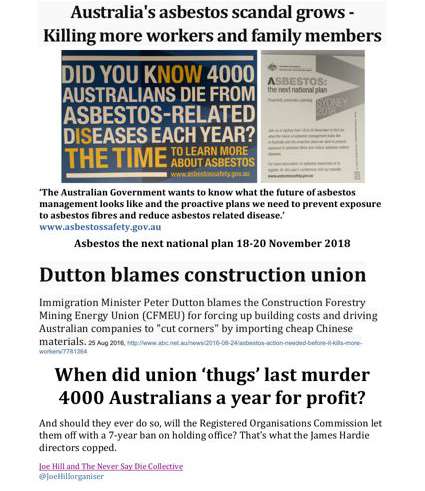

While this country struggles not to ban this killer, let never forget to add that on the Commonwealth’s own estimate, 4,000 Australians will die this year, and every year for a long time to come from asbestos related conditions.

Killing for profit is no crime.

The following few paragraphs are from McQueen’s, Framework of Flesh: Builders’ Labourers Battle for Health and Safety about the first deadly waves of silicosis in Australia.

Working conditions for some labourers improved with the arrival of steam-powered circular saws around 1840. The machines reduced the work in the saw pits which was vile because the sawdust fell on the man below, clogging eyes and lungs.

The city of Sydney has been built on 98 percent sandstone. Sewerage, the underground rail, and the excavations for high rises or even for suburban blocks have generated clouds of deadly silica. In a series of articles, Peter Sheldon told how hundreds of young men died as “rock choppers” and how they and their fellows fought for their lives. Many of the survivors went onto labour on building sites.

New South Wales introduced Workers Compensation (Dust Diseases) Act in 1942. In 1967, amendments covered 25 conditions including asbestosis. By October 1972, 87 claims had been accepted, with 19 deaths, 15 from dusting of one kind or another. Six widows got payments after post-mortems on their husbands who had not claimed. Most had been smoking about 20 cigarettes a day. By early 1973, compensation had been paid to 496, of whom 407 had died.

Specialist Medical Officer Robert Barnes wrote to the journal of the MBA, 12 February 1973:

Legislation will be introduced, but the Department of Labour and Industry inspectors are hard pressed in the policing of all hazards in all industries to which the legislation administered by the Department of Labour and Industry apply and unless unions, workers and employers alike co-operate to ensure dust control methods are used, the numbers in this State with silicosis can only be expected to grow to epidemic proportions. Mlk 04268

A popular mistake was that working in the open air eliminated the risk.

Silicosis was widespread among jackhammer operators. In one case a man aged 44 years had worked for seven years as a jackhammer operator, mainly in pier holes. During the last two years, he had complained of increasing breathlessness at any exertion. An examination revealed that his lung-functions were down to 50 per cent of normal. An X-ray showed widespread silicosis. The Board awarded him a 100 per cent pension. (J Keogh, inspector, Workers Comp Dust Diseases Board c. 1971)

The Minister advised on 1 August 1971 that “control of dust arising from excavation work generally had been under consideration for some time now.” Indeed, it had been under consideration for seventy years. Mentioned that if a bad case then should report to inspectors. (Mlk 04266)

The unions attempted to use concern about inconvenience of dust to the public to win protection for on-site workers. On 1 September 1972, Bud Cook wrote to Labor Council Secretary Ralph Marsh stressing the hazards from dust on all city sites. “Boom brings fatal dust pollution” headlined the Daily Telegraph. (5 October 1972.)

The International Labour Organisation set the standard safe minimum at 200 rock particles per cubic centremeter of air. At one skyscraper site in the CBD, the level was up to 6,000.

Water spray

In June 1972, the Metropolitan Board of Water Supply and Sewerage Employees Association moved to improve the work conditions of its members on jack-picks by all employers similar to those used by the MWSD Board. The dust could be reduced massively with a $10 water spray. The device had been developed by Board employees and was available free to other employers:

Control of dust on jack picks, drills, scabbers etc is relatively simple and inexpensive and consists of a cone-shaped metal attachment to the jack pick itself, which is connected to a mains or tank water supply and sprays the sandstone rock as the pick breaks it up. (Barnes to MBA)

The water sprays were not fitted on the excavations for the Eastern suburbs railways until 1971 after an inspection in February. The count of rock particles per cubic centremeter of air in the tunnel had been 90 times the ILO standard.

Dr Eva Francis, Scientific Officer from Health Commission addressed a Lidcombe conference on 27 July 1973. The evidence about the hazard was so overwhelming that it was “almost an academic exercise to take a dust test in dry conditions in Sydney sandstone.” She went on to ask: “What are some of the reasons for the conditions found in the city excavations?”

Firstly, there is the problem of a largely non-English speaking work-force making communication difficult.

Secondly, there is the migratory, gypsy-like habits of the sub-contractors as compared to the permanency of say the moulders in the foundries of whom ‘dust on the lungs’ is almost a myth.

And thirdly, it is an open-air situation in contrast to the usual factory atmosphere. The men feel that they are safe in the fresh air. Indeed, the total situation on a city excavation cite would provide an interesting sociological study on Australian attitudes and working conditions. (P. 23)

The solution at least to the jack-pick problem is a simple, inexpensive coil attachment and a water flow. The Union appears to be the only hope for these men at present, as only now, in the last 3 months, that they have insisted upon it, has water been available.

Finally, the comment can only be that these men … are the new convict labour of a “progressing” Australia. What price progress? This land of sunshine, this land of plenty, cannot afford a trickle of water to go with the sandstone rations. (P. 24)

The government set up a Standing Technical Committee on Dust Control. AWU delegate Charlie Oliver never came. The BLF representative, B. Holley, did not always attend. After continuing poor attendance, the meetings became quarterly. At the third meeting, Holley reported that the BLF had embarked on a six-months campaign to eliminate the killer dust. Unsafe jobs were to be stopped for 24 hours.

A dust-control report in February 1971 at the Hotel Metropole site on the corner of Bent and Phillip Streets recorded excessive dust throughout those hours. The site operated 48-60 hours a week in double shifts. The client was the Graziers Association of NSW. The excavation sub-contractor Ford Excavations P/L, was insured with the AMP

There were no fewer than 5 pier-holes being excavated with depth ranges from 1m. to nearly 4 metres. At the base, most holes were covered with about 5cm of rainwater. Jack-pickers had no water attachments. Trenches at the far end along the base of a 20m. wall were about half a metre deep.

Eva Francis to Dust Diseases Board

Amendments to Scaffolding and Lifts Act, 1912 were gazetted on 21 September 1973. Dust Control from 1 December 1973, contractors could no longer allow dust particles to escape. (Mlk 04070)

Queensland

In mid-1929, Mrs West requested financial assistance. Her husband had contracted TB while working on a concrete mixer. He had not worked for over a year and was hobbling about on sticks. She had five children. (P. 309) The union agreed to investigate thoroughly.