This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of some of the biggest demonstrations and mass rallies ever seen in this country. On Friday 8 May 1970, an estimated 200,000 people gathered in various cities and regional centres across Australia in opposition to Australian involvement in the Vietnam War. The demonstrations, organised by many organisations, unions, community groups and political parties, under the banner of the Moratorium movement was followed by two other mass gatherings, which took place on 18 September 1970 and 30 June 1971. The Moratorium movement was not a spontaneous outburst of popular discontent; no, the coming together of so many people took years of organising.

This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of some of the biggest demonstrations and mass rallies ever seen in this country. On Friday 8 May 1970, an estimated 200,000 people gathered in various cities and regional centres across Australia in opposition to Australian involvement in the Vietnam War. The demonstrations, organised by many organisations, unions, community groups and political parties, under the banner of the Moratorium movement was followed by two other mass gatherings, which took place on 18 September 1970 and 30 June 1971. The Moratorium movement was not a spontaneous outburst of popular discontent; no, the coming together of so many people took years of organising.

The Vietnam War Moratorium mass movement was a united front of Australian people from many different walks of life, opposing military conscription and Australia’s involvement in US aggression against the people of Vietnam fighting for national liberation and self-determination.

It was an anti-imperialist movement.

The Vietnam War movement emerged in 1962 and grew from a handful of activists into a nationwide mass struggle throughout the 1960s and early 1970s. In 1970 under immense pressure and persistence by the majority of Australian people the Liberal government started to withdraw Australian troops from Vietnam. In 1972 the newly elected Whitlam Labor government finalised the withdrawal of all troops and ended conscription.

The unyielding resistance of the Vietnamese people under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh and the Communist Party of Vietnam inspired and mobilised struggle against US imperialism around the world. The global struggles against the Vietnam War and US imperialism were part of the worldwide movement and rebellion against imperialism and capitalism in that period.

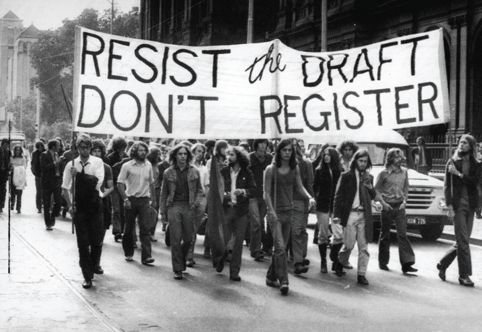

Organisation of the nationwide 8th May Moratorium mass rallies across Australia was the culmination of years of mass work, protests, and wide ranging activism by broad cross sections of Australian people. Mass resistance and civil disobedience, defying and breaking laws; arrests and imprisonments; strikes and stop work meetings by workers, unions, university and school students; militant protests outside US embassies and corporations; occupations of universities, US chemical and weapons companies and magistrate courts; signing petitions, letterboxing millions of homes, street meetings and public protests; passionate discussions and arguments in homes, workplaces and in the community, characterised a vibrant and dynamic people’s movement.

The Vietnamese people’s struggle for national liberation and freedom from imperialism

The Vietnamese people’s war against US imperialism was the extension of their long revolutionary struggle for national liberation from French colonialism and Japanese militarism. In the early 1950s, the US, alarmed at the French defeats at the hands of heroic Vietnamese people, intervened to help the French colonialists to crush the national liberation struggle. In early 1954 the Vietnamese people, led by Ho Chi Minh and the Communist Party of Vietnam, overthrew the French colonial rule. The US saw an opportunity for themselves to replace the French as the foreign power controlling Vietnam.

The Vietnamese people’s war against US imperialism was the extension of their long revolutionary struggle for national liberation from French colonialism and Japanese militarism. In the early 1950s, the US, alarmed at the French defeats at the hands of heroic Vietnamese people, intervened to help the French colonialists to crush the national liberation struggle. In early 1954 the Vietnamese people, led by Ho Chi Minh and the Communist Party of Vietnam, overthrew the French colonial rule. The US saw an opportunity for themselves to replace the French as the foreign power controlling Vietnam.

Vietnam was temporarily divided into 2 zones at the 17th, parallel with UN calling for elections scheduled within 2 years. The US conspired with its puppet South Vietnamese governments ensuring no elections were held. Instead, for the next 20 years the US installed and bankrolled a succession of corrupt and brutal puppet regimes unleashing a reign of terror on the people of Vietnam.

“US leaders had no intention of allowing a free election because they knew- President Eisenhower actually made the admission – that more than 80 per cent of the population would have voted for Ho Chi Minh against former emperor and pro-Western puppet Bao Dai. Washington swiftly wheeled in a new stooge, Ngo Dinh Diem, a Vietnamese aristocrat living in New York with absolutely no following in Vietnam. Diem, described by President Johnson as the ‘Churchill of Vietnam’, immediately cancelled the elections promised for July 1956.” Joan Coxsedge, Background to the Vietnam War.

The 1950s and 1960s was a period of persistent barrage of Cold War anti-communist rhetoric, rhetoric that formed the backdrop for many growing up in countries of the advanced capitalist West, in the post World War 2 period. The domino theory a ‘theory’ that purported to show that with the advent of Communist Party rule in China and the rise of popular resistance forces in South East Asia in particular, states in the region could fall under communist control, one after the other like tumbling dominoes. Against this background in early 1960s, the Australian public opinion supported Australian involvement in the fighting in Vietnam and cosying up to US imperialism.

In 1960, Ho Chi Minh and the Communist Party of Vietnam provided political leadership for the formation of National Liberation Front of South Vietnam. The NLF was a united front of many groups in South Vietnam – peasants, urban and rural workers, health workers, teachers, doctors, engineers, Buddhists, patriots, Communists, liberals. Guerrilla resistance by the National Liberation Front to US occupation and the brutal puppet government strengthened and intensified.

By 1967 the US had sent 485,600 soldiers and military personnel to crush the Vietnamese people’s fight for national liberation. The US dropped more bombs on Vietnam than the overall number of bombs dropped on Europe during WW2. The US sprayed more than 21 million gallons of toxic defoliants and herbicides over South Vietnamese villages and countryside to uncover and flush out the NLF guerrilla fighters. The defoliants included most poisonous chemicals Agent Orange and Dioxin. In the ten years nearly 400,00 tons of napalm was dropped on the Vietnamese people.

“All the way with LBJ” – Australia follows Uncle Sam

In 1962 the Australian government, a compliant and loyal ally of the US since WW2, dispatched 30 military advisors to serve alongside the US army and its South Vietnamese puppet government forces. In 1964 the US called again on its most obedient “ally” to start sending combat troops to South Vietnam. The Australian government jumped to the US command and, even before parliament officially declared war on Vietnam in 1965, the National Service Act (conscription) was legislated in November 1964, making it compulsory for all 20-year-old males to register for national service to fight in Vietnam.

On a visit to the US in June 1966 the Australian PM Harold Holt pledged Australia’s servitude to the US and its President Lyndon Johnson, proudly declaring Australia was “all the way with LBJ”.

Between 1965 and 1972 about 60,000 Australia ground troops, naval and air force men were sent to fight in South Vietnam. 521 Australian soldiers were killed and 3,000 wounded.

Struggle, unity, resistance and mobilisation against Vietnam War

The 8th May 1970 Vietnam War Moratoriums are mainly known for the mass rallies that drew between 150,000-200,000 people into the streets of cities and regional centres across the country. They were the biggest protests in Australia’s history up to that time.

The 8th May 1970 Vietnam War Moratoriums are mainly known for the mass rallies that drew between 150,000-200,000 people into the streets of cities and regional centres across the country. They were the biggest protests in Australia’s history up to that time.

The 8th May mass mobilisations were the culmination of many years of organised work and struggle by tens of thousands. It was a broad and diverse anti-war movement engaging and uniting people from different walks of life, political views and backgrounds.

The political direction of the anti-war movement was constantly discussed, vigorously argued and tested in practice. Calls for the defeat of US imperialism and support for the National Liberation Front and the Vietnamese people’s armed struggle for national liberation were widely explained, promoted and acted on. With experience, and increasing exposures of US aggression and growing respect for the heroic Vietnamese people, calls to end US imperialist aggression and Australia’s subservience to US imperialism were more widely accepted.

Many in the anti-war movement understood the necessity for principled unity to build a broad mass movement on key demands. In the unity and struggle of this broad united front anti-imperialist working class politics were vigorously promoted.

Opposition to Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam war had started in 1962 and built up almost immediately after parliament passed the National Services Act (conscription) in 1964. At first a small number of women set up Save our Sons, a national network of women opposing conscription. A few young men started to refuse to register or declared themselves conscientious objectors. By 1972 more than 100 draft resisters and conscientious objectors were in hiding or served time in gaol under the Crimes Act. Many were on the run for years, protected and hidden in people’s homes and union offices.

Hundreds of active grass roots anti-Vietnam war groups and organisations sprung up across the country in workplaces and unions, schools, universities, religious organisations, communities and neighbourhoods. Organising local discussion groups, public meetings and rallies in workplaces, communities and neighbourhoods. There were millions of homes letterboxed and poster paste ups during the night. Anti-war concerts, performances and street theatre in the suburbs and shopping centres.

Stop Work to Stop the War!

The core and backbone of the anti-Vietnam war movement in Australia was the organised working class and militant unions without whom the movement could not have grown in numbers, militancy and strength. Militant workers and unions led and inspired the anti-war movement. Workers’ and unions’ call Stop Work to Stop the War echoed across the country. Wharfies, seafarers, metal workers, plumbers, printers, electricians, shearers, mining workers, food workers, teachers, meat workers, railway and tramway workers, public servants stopped work to attend rallies. In factories, offices, schools and universities motions and resolutions calling for an end to conscription and the Vietnam war were enthusiastically supported. Hundreds of thousands signed petitions.

As early as 1966 builders’ labourers, wharfies and seamen, led by Communists, regularly walked off the job in opposition to conscription and US imperialism. Wharfies and seafarers in Melbourne and Newcastle refused to load and crew military cargo ships Boonaroo and Jeparit bound for Vietnam. In Sydney, seafarers placed a ban on U.S. warships. The nation wide Penal Powers struggle led by Clarrie O’Shea and the Victorian Tramways Union members in May 1969 inspired and instilled confidence in workers, unions and many others.

The working class was active in the political class struggle against imperialist wars, echoing Clarrie O’Shea a year earlier “If the workers confine themselves merely to economic questions, they confine themselves in a very narrow sphere. It is necessary to go further than mere economic questions. For myself, I believe you must end capitalism altogether…It is all coming to a great fight. And I believe the workers and working people must prepare for this.”

The power of mass movements

It was a truly broad united front mass movement. People joined in activities at all levels from signing petitions, attending local suburban meetings and rallies, holding meetings in workplaces, people’s homes and streets. For years angry and militant protests were held outside the US embassies and consulates, calling out “Yankee Go Home”. US flags were burned and public declarations of independence from US imperialism were made outside US Consulates on 4 July. Occupations in universities, schools, government offices and even a Melbourne Magistrates’ court.

Defying the Crimes Act and the threat of long gaol sentences workers and students publicly collected funds for the Communist led National Liberation Front of South Vietnam.

By 1969 the majority of Australian people were calling for our troops to be brought home from Vietnam. More young men refused to register or declared themselves as conscientious objectors.

In early 1970 a national Vietnam Moratorium committee was formed. It was an organisational expression of the united front mass movement of hundreds of grass roots and official organisations (unions) united on immediate demands to end conscription, withdraw Australia from the war and end Australia’s support for US imperialism and the US-Australia alliance.

On 8th May close to 200,000 people poured into the streets of major cities and regional centres demanding an end to the war. In Melbourne 100,000 took over the streets of 5 city blocks and sat down in the centre of the city. The sheer numbers of protestors from different walks of life shocked and paralysed the 1,000 police hiding behind state parliament, on standby ready to provoke and attack the protestors, make mass arrests and break up the march.

In Adelaide the 8th May Moratorium rally led to the 4th July becoming an annual expression of anti-imperialist action. In Sydney tens of thousands of workers, teachers and students walked out and marched through city streets and sat down in the middle of the city.

The peaceful rallies on 8th May were in stark contrast to Moratorium rallies held later in the year with police removing their badges and viciously attacking protestors.

By 1972 the Vietnamese people were winning the war against US imperialist aggression, bolstering confidence of the anti-war movements across the world, including Australia.

The consistent and patient mass work over the years amongst workers and in communities laid the groundwork for significant growth and success of the campaign against Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam war. It was the independent mass movement of tens of thousands relying on mass mobilisations, not parliament, that ended conscription and Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam war.

The 1960s and early 1970s Vietnam war struggles galvanised the fight to end US imperialist control of Australia. The legacy of the anti-Vietnam war campaign and mass movement holds many lessons for us today in the unfinished struggle to end US domination in the fight for an independent socialist Australia.